The Wonderful World of Opera Dogs: Rudolf Bing At the Met – Divas, Divos & Dogs

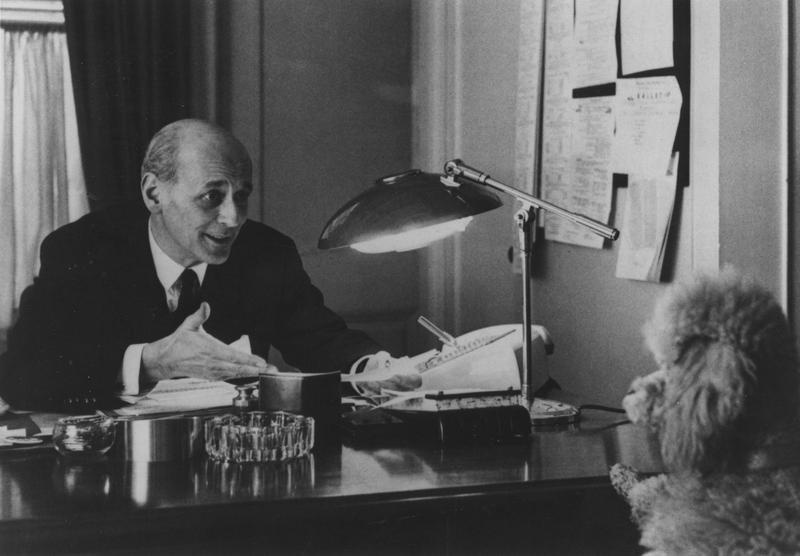

By Diana Burgwyn(Photo Credit: Alamy Stock Photos)

OperaWire is proud to present The Wonderful World of Opera Dogs, a series by Diana Burgwyn, which will focus on the relationship between opera’s most iconic stars and their beloved canines. The creation of this series and all research necessary for each individual piece was conducted solely by Diana. To learn more about the origins of the project, click here.

Rudolf Bing, the Vienna-born general manager of the Metropolitan Opera from 1950 to 1972, was known for his reserved, aristocratic manner, his cutting (sometimes brutal) wit, and autocratic behavior.

Bing was not the type of man you’d expect to be a dog lover. He seemed too fastidious to have an animal shedding on his oriental rugs and chewing the furniture. But he was enchanted with Dachshunds and had several of them in sequence, all named Pip. Photos show Bing lying happily on the floor, dog bone in hand, while the current Pip gnaws on it.

A near-crisis occurred in Bing’s life when his wife, Nina, took Pip for their usual daily walk and was startled by a huge, ferocious dog that charged at him. Fearful that Pip would be eaten alive, Nina interceded and was herself bitten by the beast, necessitating a rabies test. During an agonizing wait for test results, her husband coped by making a list of people whom Nina would bite if she did have rabies. Fortunately, she did not. Fortunately, too, the list of intended victims apparently vanished before it could be seen by anyone at the opera house.

Clearly, dogs served to soften the heart of this stern man. He was nothing but sympathetic when Maria Callas’ poodle, Toy, relieved himself on one of the stage trees during a dress rehearsal of “Norma.” “Pip would probably have done the same,” Bing told her. This did not, however, prevent him from firing the star for her “irritating” demands (he later rehired her).

Callas & Her Poodles

Callas, the legendary New York-born soprano born of Greek parents in 1923, was one of the most electrifying singers in operatic history. Her voice was instantly recognizable, powerful, and capable at its best of remarkable flexibility and range, and her dramatic command of every role she sang was uncanny, whether it was Norma, Lady Macbeth, Tosca, Brünnhilde, or one among many bel canto heroines.

Callas’ first dog, Toy, a miniature black poodle, was a gift from her good friend, the stage director Luchino Visconti. She treated Toy like a beloved child and kept him meticulously groomed; he slept at the foot of her bed. It seemed that all of Paris showed up at Orly Airport when Callas arrived in a beige mink coat and velvet hat, Toy in her arms chewing happily on the orchids with which his mistress had been greeted. Toy went everywhere with Callas, his bathroom etiquette lacking not only at the Met but at composer Samuel Barber’s home when he and Callas discussed her taking the leading role in his new opera, “Vanessa.” She even showed up with Toy at a pre-trial hearing on a claim made by her former agent.

Photos over the years record the presence of Toy and his canine successors–Callas showering with them, combing them, handing them treats, holding court with them in her dressing room. While the dogs certainly added to her public allure and accented her fashionable attire, they were far more to her. They were the children she longed for but never had, as well as her most faithful companions.

Callas had a seemingly happy, decade-long marriage to the much older, wealthy Italian industrialist Giovanni Battista Meneghini, who provided her great financial and personal support. But in 1959, she announced to her shocked husband that she wanted a divorce. By then Toy was quite old, and another poodle, Tea, had joined them. After absorbing the painful news, Meneghini remarked: “If everything will be split and if we have to divide this poodle [Tea], Maria will get the front end and I will end up with the tail!” Not quite: Callas won ownership of Tea, front end, and tail.

It was at this time that Callas became involved with the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, a charismatic, arrogant, woman-chasing multi-millionaire, who divorced his wife and became the all-consuming object of Callas’ love. Newspapers followed the ups and downs of the affair wherever they went. The relationship ended miserably in 1968 when Onassis suddenly married Jacqueline Kennedy, widow of the American president John F. Kennedy. This was the cruelest blow of Callas’ life.

Her voice was at its peak early in her career but began to decline in the 1960s. Her vocal decline gave rise to accusations, true or false, about the cause was her major weight loss–about 80 pounds. As her career petered out, gossip about her voice and her life spread.

Callas became more and more dependent on her poodles, making this sad comment: “Only my dogs will not betray me.” When, in 1971-72, she held a series of masterclasses in New York City (the subject of a 1995 play by Terrence McNally), she missed her dogs so much that she had her maid, Bruna, fly them in from her apartment in Paris.

The day Callas suddenly died in Paris, September 16, 1977, at age 53, she was attended as usual by Bruna and the butler, Ferruccio. Her two aging dogs, Pixie and Djedda, gifted to her by Onassis, were in her bedroom. Facing her bed hung a large oil painting of Toy, created after his death. Suddenly, Callas experienced a piercing pain on her left side and fell on her way to the bathroom. The servants found her slumped on the floor, lifted her onto the bed, and gave her coffee. Calls for an ambulance were not answered and Callas’ heart failed. Bruna reported that the dogs, which were in the bedroom with her, were removed to another room where they whimpered pitifully.

A longtime friend, Nadia Stancioff, described her visit to the apartment days after Callas’ death. “Bruna looked older and lifeless. In her arms, she cradled a trembling Pixie, whose cataract-covered eyes blankly searched my face for recognition. When I patted her, a high-pitched bark shook her little body, and she wouldn’t let me hug Bruna until she’d licked my hand and ascertained who I was.”

Tebaldi’s Operatic Canine

Maria Callas’ “major rival” was the Italian lirico spinto Renata Tebaldi; she had one of the most beautiful voices of the 20th century: rich, plummy, velvet, warm, with ravishing pianissimi. Among the singer’s most successful roles were Tosca, Mimi (in Puccini’s “La bohème”), Desdemona (in Verdi’s “Otello”), and the title role in a lesser-known opera that she championed: “Adriana Lecouvreur” by Cilea. Only her top register failed Tebaldi, becoming pushed and strident over the years. She was a classic beauty as well, with patrician features. Tebaldi’s angelic manner, however, believed her determination (Bing took note of Tebaldi’s “dimples of iron”).

Renata Tebaldi never married, though she had various liaisons. Nor was she concerned over being childless, given her intense performance schedule. Her most important and steady companion was her mother, Giuseppina, a former nurse, who accompanied her wherever she sang. Giuseppina was something of a gendarme, a take-charge mother of strong opinions.

After first objecting when her celebrated daughter expressed the desire to have a dog (a medium-sized grey poodle), la mamma finally gave way, and New I became part of the family, as did New II, his successor. New had quite a wardrobe, composed of dog-sized facsimiles of his mistress’s operatic costumes, including a specially made western outfit, stitched together from the leather cuttings left from Tebaldi’s attire as Minnie in Puccini’s “Girl of the Golden West,” complete with holster and pistol. The outfits were painstakingly made by Tebaldi’s loyal fan and maid, Tina Viganò, whose support was crucial after the sudden death of Tebaldi’s mother at age 68. New even made it to the stage with roles of his own, such as Musetta’s dog in “La bohème” and the Marschellin’s dog in “Der Rosenkavalier.”

Evidently New had operatic ambitions of his own, because on one occasion when Tebaldi warmed up in her dressing room, he did as well. She enjoyed these duets, but the howling enraged a certain Franco Corelli, who was vocalizing in his own dressing room. Only half-dressed, he stormed into Tebaldi’s room and berated both singer and dog. Corelli’s tantrum was rather foolish since he had his own adored poodle, Loris, who was not above singing a phrase or two while his owner vocalized. Eventually tenor and soprano developed a close working and personal relationship; there were even rumors that they had a short affair.

Credit: University Musical Society

Corelli & Loris

Franco Corelli was one of the most handsome tenors in Metropolitan Opera history—tall, muscular, with penetrating brown “lady-killing” eyes and a huge chest. His thrilling voice was described as a force of nature, and his characterizations were equally powerful. Corelli was also probably the most neurotic singer that Rudolf Bing encountered in his 22 years at the Met. Not only did he make endless demands on the company, but he could be downright nasty. When upstaged by a fellow artist, Boris Christoff, he stabbed the shocked basso in the hand, and when an operagoer booed him he exited the stage and ran up three flights of stairs intending to attack him.

Underneath all the bluster was a pathologically insecure man. Before appearing on stage, Corelli typically turned white with fear; those who saw him in the wings said he looked like he was preparing for the guillotine. He often had to be coaxed on stage, and his wife, Loretta, a former singer, would stand in the wings carrying a picture of the Madonna and sprinkling him with holy water.

Why did Rudolf Bing put up with all these shenanigans? Of course, being a matinee idol, Corelli had legions of fans who filled the house and brought in the money. And, given Bing’s tolerance toward canines, he considered Loris to be a member of the Met family. But he certainly wasn’t expecting what happened on May 13, 1961.

The Met was in Chicago, preparing for a performance of “Turandot” with Corelli and Birgit Nilsson, the Met’s reigning Wagnerian soprano. Bing’s phone rang in the middle of the night; Loris was very ill and Franco and Loreta were sobbing frantically. A veterinarian was called to their hotel, determining that the dog was having seizures, which he was able to stop. Later, Loris began to hemorrhage. He was taken to an animal hospital, and an unwilling Corelli was escorted to the opera house. Bing provided him with the piano that Nilsson had been warming up with, which did not please the soprano. “Mr. Bing,” she said, “I am wondering if it would be better to be a dog in your opera house than a singer.” Corelli had to be led to the stage, protesting that he couldn’t sing. He could and he did.

The next day, as Corelli arrived in Detroit by train for his next performances, he insisted that he had to speak to Loris, who was still in the animal hospital in Chicago. The call was made, Loris obediently moaned into the receiver, and Corelli was satisfied.

On the whole, Birgit Nilsson accepted Corelli’s shenanigans, since she genuinely admired his voice and felt sympathy for his emotional difficulties. Having been a farm girl (her father was a sixth-generation farmer), she also loved animals, often taking a leave from opera and returning home to Sweden to milk the cows and reconnect with her beloved horses. Her special way of announcing mealtime for the six cats on the farm was to belt out a high C, which brought them running from every corner of the yard. And she preferred dogs to children. A German shepherd, she said, will sit with you all evening listening to Mahler whether or not he likes it, then give you a lick and go off to bed.

On April 23, 1972, Sir Rudolf Bing retired as general manager of the Metropolitan Opera. He had accomplished a great deal in his 22 years there, bringing some of the world’s most important singers, demanding better acting, hiring adventurous new stage directors, and finally breaking the racial barrier that had prevented any black singers from taking major roles.

On his last morning at the Met, Bing, attired in a grey coat and bowler, took Pip out for their customary walk. Pip wore a green wool sweater.

© Copyright 2021 Diana Burgwyn

Categories

Special Features