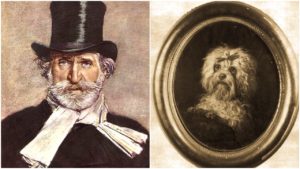

The Wonderful World of Opera Dogs: Giuseppe Verdi’s Hunting Companion & Pampered Pet

By Diana Burgwyn(Lulu Picture Credited to Alamy)

OperaWire is proud to present “The Wonderful World of Opera Dogs,” a series by Diana Burgwyn, which will focus on the relationship between opera’s most iconic stars and their beloved canines. The creation of this series and all research necessary for each individual piece were conducted solely by Diana. To learn more about the origins of the project, click here.

The dog Blach had a privileged life. He feasted on macaroons, slept anywhere he wanted in the big villa, was provided the biggest bones, and had his own secretaries, male and female. We know this because Blach (also known as Black), a tall, lean, and powerful hunting dog, described his privileged life in a letter that he wrote to his canine friend Ron-Ron. In the letter, he mentioned one of the secretaries, who served as his major-domo secretary factotum. That individual had the strange habit, wrote Blach, of scribbling little hooks on paper.

The truth, of course, is quite different, for it was the creator of the little hooks on paper who wrote a letter in the dog’s name: Giuseppe Verdi.

Whoever would have thought that one of the greatest composers of all time would have the time or desire to pen such letters? After all, this was a man who composed well over 20 works for the stage, many of them a staple of every major opera house in the world. To imagine the repertoire without such operas as “Aida,” “Rigoletto,” “Falstaff,” “Il trovatore,” “Un ballo in maschera,” “La traviata,” “Otello,” “La forza del destino,” “Macbeth,” and “Don Carlo” is unthinkable. Verdi was also a major political figure, active in the movement that reunified the different states of the Italian peninsula into a single nation.

Still, the composer liked to say that he was a farmer who occasionally composed music.

He had a huge estate of 2500 acres surrounding an elegant villa in the town of Sant’Agata, which was in the province of Piacenza not far from his birthplace. For Verdi, dogs were a pleasant part of everyday farm life. They guarded the property when he was away; when he was at home they kept unwanted visitors from bothering him and accompanied him when he hunted. Blach shared his home with many other species—peacocks, cats, parrots, pheasants, and chickens, among them.

Blach’s pen pal Ron-Ron had an equally good life with Count Opprandino Arrivabene, a prominent Mantua-born journalist, art critic, and poet of noble birth who shared Verdi’s fervent support of Italian nationalism. Their close friendship was recorded in a correspondence of over 200 letters spanning 50 years. Arrivabene, following Verdi’s lead, was happy to answer Blach’s letters with gossipy ones penned, of course, by Ron-Ron. Evidently, the two dogs were great pals, because if Ron-Ron didn’t show up for frequent visits in Sant-Agata, Blach was not happy.

“My beloved brother,“ wrote Verdi in Blach’s voice, “you were very wrong not to come to see me, for I would have received you with open paws and open jaws and my four teeth in your wooly cheeks; I would have shown you all the tenderness I, a dog, can muster.”

Also in that letter was a critique of the Verdi household: “….we have a rather large number of imbeciles whom we whack with our paws every once in a while, just to get them back in line.” The greatest imbecile was clearly his major-domo secretary factotum, who continued to scribble hooks on paper and whom Blach planned to “enroll in the list of madmen.”

Blach’s eventual decline was reported to Arrivabene in a sad but witty post, revealing Verdi’s genuine affection for the dog.

“My poor Blach is quite sick,” he wrote. “He barely moves and will not live long. I have ordered another Blach to be manufactured in Bologna, because if it came into my head to write another ‘Don Carlo,’ I could not do it without a collaborator of that species.”

Soon after came this: “Blach is dead!!! He was not old, but he lived too happily” (a surfeit of macaroons, perhaps?).

Lulu / Loulou

Among Verdi’s many dogs, one stood out as being entirely different from Blach and the other canines. This was a Maltese, whom Verdi called Lulu. A male despite the name, Lulu preceded Blach chronologically and was undoubtedly the all-time favorite dog of Verdi and his companion (whom he later married), Giuseppina Strepponi.

Verdi had suffered two tragic losses early in life: his two infant children and then his young wife. In the mid-1840s he began to live with Strepponi, a highly gifted soprano who starred in a number of his earlier operas and excelled in the bel canto repertoire but had retired young because of a relentless performing schedule and a number of out-of-wedlock pregnancies that badly affected her voice. Recent research has provided speculative but convincing evidence that both she and Verdi had abandoned illegitimate children. Giuseppina did not abandon animals, however—she collected them.

It is possible that Lulu was given to the couple by Francesco Maria Piave, a Verdi friend, librettist and fellow nationalist, who made a visit to Sant’Agata at that time. Verdi had written to him: “Come quickly then, and, if you can, bring a lion with you, which you know will delight Peppina.” The Maltese, considered a toy dog at less than seven pounds, was a safer choice.

Lulu (generally referred to as Loulou by Strepponi) stole the hearts of the couple. Who could resist that flowing, all-white mantle, the elegant, effortless gait, the big dark eyes and black nose, the charming personality? Lulu was an especially great comfort to his mistress, who resented their rural neighbors’ gossip about them and compared them unfavorably to Loulou. In her bedroom, she had oil paintings of both the dog and the couple’s parrot, Lorito.

Writing to Léon Escudier, Verdi’s French publisher, Strepponi claimed that “My Loulou [note the possessive] is the most beautiful dog in the world, and all the world has to obey him.” Verdi, she added, would walk around with Loulou under his jacket to prevent the dog from catching a chill but with his nose outside the jacket so he could breathe. Loulou even had his own passport, accustomed as he was to traveling everywhere with the couple.

The dog’s great adventure was in Naples, where he accompanied Verdi and Strepponi in 1858 for rehearsals of the opera “Simon Boccanegra.” Verdi had become friendly with Baron Melchiorre Delfico, known as the “prince of caricaturists,” and during the Naples visit Delfico created a series of drawings depicting Lulu with the composer as they arrived at the port, together chose the singers, rehearsed them, instructed them on how to sing, met friends, visited the doctor, and were hassled by an admiring public.

Lulu became very ill the next year. Maltese are delicate dogs, and it is possible that he had been weakened by the long journey he took with Verdi and Strepponi from Rome to Civitavecchia. The voyage involved 19 miserable hours at sea, during which Strepponi also became quite sick. Lulu’s death in July of 1859 was a terrible blow. Giuseppina wrote that she and Verdi had cried like babies “to see those beautiful eyes shut, eyes which had gazed at us with such love.”

The conductor Angelo Mariani was intending to pay a visit to Sant’Agata in the company of a British diplomat at precisely that time. Writing to him, Verdi explained the situation: “A very grave misfortune has struck us and made us suffer terribly. Loulou, our Loulou is dead! Poor creature! The true friend, the faithful, inseparable companion of almost six years of life! So affectionate, so beautiful! Poor Loulou! It is difficult to describe the sorrow of Peppina, but you can imagine it…..How happy I would feel to receive someone in my house whom I love and revere so, and you know I speak sincerely. But, my dear Mariani, in my house now there is desolation.”

A tantalizing mystery regarding Lulu exists to this day. In 1901 a British literary publication, the Pall Mall Magazine, contained a detailed reminiscence of Verdi by one M. de Nevers, who was a student of the opera composer Amilcare Ponchielli, and who had met Verdi two decades before. Verdi and Count Arrivabene, he claimed, having become convinced that their two Maltese dogs were in love, wrote a series of romantic letters in their names. Given the letters “authored” by Blach and Ron-Ron, it is not difficult to accept M. de Nevers’ contention that the men endeavored “not only to guess the thoughts of their pets but also to express them in quaint dog language.” The letters were, he wrote, under lock and key in the vaults of the Arrivabene family.

Today Verdi’s massive correspondence is housed in a number of different collections: at Yale, at the retirement home he founded, at an institute for Verdi studies in the U.S., in private collections. Many are inaccessible to the public. Are Lulu’s love letters still with the Arrivabene family? The curious researcher is left to imagine their many charms.

Giuseppe Verdi lived until age 87, his last opera (and second comedy), “Falstaff,” having been composed when was almost 80. He died in Milan of a stroke, mourned throughout the nation and beyond. As he requested, Verdi was buried in the municipal cemetery alongside Giuseppina, who had predeceased him. So great was his fame, however, that the two coffins were later removed and, after an elaborate state funeral, placed in an imposing vault in the Casa di Riposa per Musicisti (Musicians’ House of Rest), which had been founded and funded by the composer.

Lulu is buried in the tranquil garden of Verdi’s villa, its paths bordered by poplar and exotic imported trees leading to a winding lake. Here he lies under a small shaft of marble with the inscription, “To the Memory of a True Friend.”

Categories

Special Features