The Wonderful World of Opera Dogs: Galina Vishnevskaya the Soprano, Rostropovich the Cellist & Pooks the Pianist

By Operawire Staff(Credit: New York World-Telegram / Wolfson, Stanley)

OperaWire is proud to present “The Wonderful World of Opera Dogs,” a series by Diana Burgwyn, which will focus on the relationship between opera’s most iconic stars and their beloved canines. The creation of this series and all research necessary for each individual piece were conducted solely by Diana. To learn more about the origins of the project, click here.

The mood at Shermetyvo Airport, Moscow, on May 26, 1974, was tense. Galina Vishnevskaya, a handsome, dark-haired woman in her late 40s, was trying without success to convince her 200-pound Newfoundland dog Kuzya to get up from the floor. Finally, joining Kuzya on the floor, she patiently assured him that he was not being given away to anyone and that he would be traveling to England with her husband, his master.

Kuzya eventually allowed himself to be led into customs. There stood the renowned cellist Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich. Kuzya threw himself at his master joyfully. Less happy was Rostropovich, who was being frisked as if he were a criminal. He was told that he could not take any money with him on the flight, and he was even denied the prestigious gold medals awarded him by national governments. Vishnevskaya wrapped them in her husband’s pajamas and took them home for safekeeping. Rostropovich departed his country with one suitcase, two cello and Kuzya on a leash.

The cellist and his wife, an operatic soprano of equal stature, were ostensibly taking a two-year leave of absence from the Soviet Union for the purpose of performing abroad. In actuality, however, they were being forced out of their beloved homeland because of their courageous support of such composers as Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev, who were out of favor with the Communist regime, as well as their close friendship with the dissident writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

The flight to England was uneventful, but the arrival at Heathrow Airport in London was not. A six-month quarantine for dogs had been in effect in England for almost a century because of the threat of rabies. Although Rostropovich had been aware of that, he had no idea that Kuzya’s feet would not be allowed to touch British soil, so he came bounding down the steps of the plane with the cooped-up dog straining at the leash. The officials froze and ordered them back into the plane while the van from the kennels drove from the hold to the front steps.

Annoyed, Rostropovich said to a student who had accompanied him on the flight: “And where do you suppose I could have gotten a cage for a dog that weighs 90 kilos?” He calmed down when the officials told him he could visit Kuzya whenever he wanted during the quarantine. The dog, however, had the last word: he left a large and odiferous present in the cabin for the Brits.

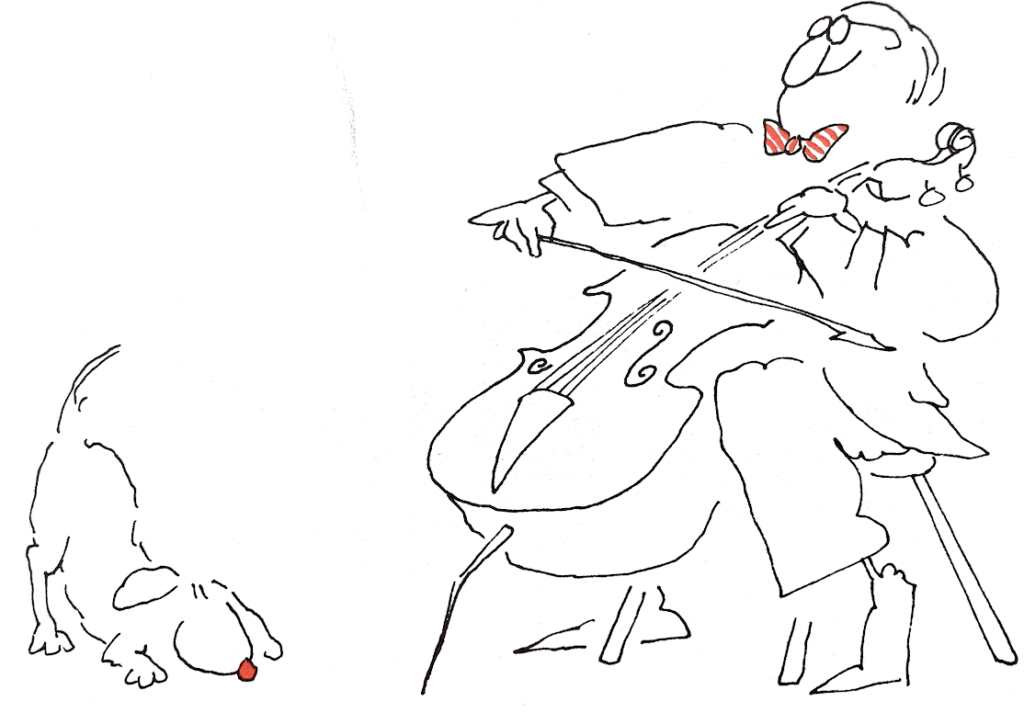

(Credit: Christopher L. Demarest ©1983)

A Painful Departure

The forced departure of Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya was a blow to the couple and to the Soviet Union, for they had both brought musical glory to the country. Rostropovich had been the Soviet nation’s major cultural ambassador to the world of classical music, revered then and now as one of the greatest cellists of the 20th century. Vishnevskaya had commanded an almost royal position in Russian musical life at the Bolshoi, where she sang the great soprano roles, notably Tatyana in Tchaikovsky’s “Eugene Onegin,” with her husband often at the podium. They had a spacious country villa, or dacha, outside of Moscow, complete with all amenities and the powerful—but gentle—Kuzya standing guard.

With increasing Communist control, however, the couple’s unwillingness to abandon their out-of-favor colleagues caused severe restrictions in their lives and performance opportunities. Hence, the unhappy departure for England. There and elsewhere in the West the cellist was eagerly embraced by the public for his near-mystical dedication to music, the charisma he exuded onstage, and the immediately recognizable sound of his instrument. Later he took on the music directorship of the National Symphony Orchestra (NSO), leading the ensemble for 17 years. Vishnevskaya gave several powerful performances at the Metropolitan Opera, as well as recitals with her husband at the piano.

Known to friends and colleagues as “Slava” (the word means “glory”), Rostropovich charmed people with his affectionate nature: he hugged and kissed everyone, from stagehands to strangers. His immense love of life encompassed all aspects, from food to boxing, and his childlike playfulness knew no bounds. Even his fractured syntax in speaking in any language other than Russian was considered delightful.

Despite Rostropovich’s outward warmth and lavish displays of affection, some who worked with him felt they did not really know him. The comment was made by an NSO orchestra musician that his most intimate relationship seemed to be with his dog Pooks, whom he acquired after the death of Kuzya. Perhaps he had never gotten over the betrayal by his native country and was seeking the total loyalty that a dog could provide. He also bore the legacy of exile, so Pooks was his living representation of home. Indeed, Rostropovich was so jealous of Pooks’ affections that, according to one of his two daughters, he discouraged others from getting close to the dog.

Pooks the World Traveler

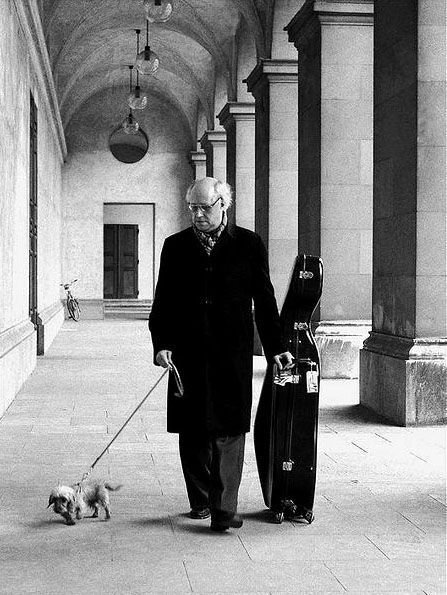

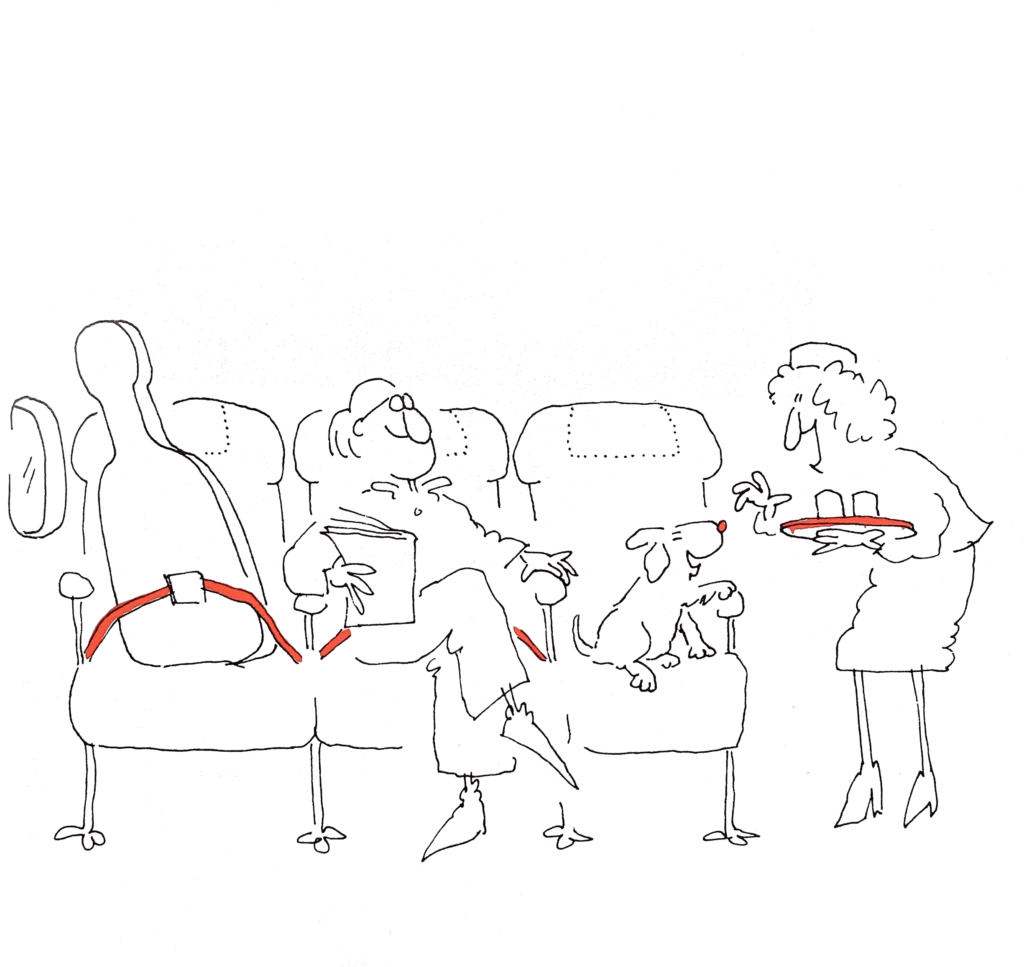

A miniature long-haired Dachshund, Pooks was quite a departure from the huge Kuzya. The advantage of his small size was that his owner could—and did—take him everywhere: around Europe, to South America, to Japan. Pooks had his own passport and a set of traveling clothes which included; one purple coat, one black turtleneck sweater, and two pairs of red boots. His normal place at rehearsals, whether his master was seated at the cello or standing on the podium, was next to him, lying on a soft rug. When Rostropovich traveled on planes he smuggled Pooks onboard in a satchel and let him loose the minute the plane took off, whatever the airline rules might have been. He always bought three tickets: one for himself, one for Pooks, and a third for his cello—his favorite being the 1711 ‘Duport’ Stradivarius.

Once, in Taipei, where Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya were to present a concert, a student walking his own dog was so infuriated when a police officer reportedly kicked the dog that he set off fireworks in the hall. The concert went on as planned, and afterwards Rostropovich sent a public message to the student, reading: “Of course all people in the world are different, and I, in similar circumstances would look for other means of protesting. But as a person whose life is tied to dogs, whom I love and respect totally beyond any understanding, I would like to send greetings from my dog, whose name is Pooks, to your dog.” At the time the cellist did not have Pooks with him because of a pet quarantine. “Therefore,” he added in his message, “….at this moment we both suffer from our separation.”

(Credit: Christopher L. Demarest)

Pooks was a star in his own right. Rostropovich insisted that he could play the piano, and whenever the opportunity arose he would instruct the dog, in Russian, to perform. Pooks would obediently climb onto the piano bench and hit the keys with his paws; he appeared to be equally at home on the white and black keys and in the soprano and bass registers. After each performance he would leave the piano but return for encores whenever the maestro deemed he had received sufficient applause. Asked what music the dog preferred, Rostropovich would reply: “He only plays modern music.” Evidently the cellist could not interest Pooks in Mozart or Beethoven.

The origin of the name Pooks was a subject of curiosity. One newspaper account cites Rostropovich as having joked about the name with the Swiss ambassador at a party and referring to it as acronym for “People’s Opposition Of Kremlin S***.” True or not, the maestro’s vocabulary, limited though it was, did not lack for salty words.

Pooks was honored with a corporation in his name: Pooks Concerts, Inc., registered in Delaware in 1977 and into which the NSO put Rostropovich’s earnings. He was also the subject of a book for children and feted by fellow dog lover Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein, himself the son of a Russian immigrant, composed “Slava! A Political Overture” for Rostropovich’s inaugural concert as music director of the NSO. Bernstein took the overture’s basic materials from his own musical play “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue,” introduced the previous year. At the end of the piece members of the orchestra were to shout “Pooks!” three times; after the dog’s death the word “Slava!” replaced it.

Rostropovich often spoke of having three musical gods: Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Benjamin Britten; the latter considered by many to have been the greatest British master of opera since Henry Purcell. The three of them, as well as other major composers, dedicated hundreds of new works for cello to Rostropovich.

A Deep Friendship Strengthened by Dogs

The friendship between Rostropovich and Britten was particularly deep and intense, born in part from their mutual courage in the face of official and public disdain. Britten was an open pacifist and a homosexual, a reserved man who worked in solitude from his farmhouse in the English coastal town of Aldeburgh, which he shared with his longtime partner, tenor Peter Pears.

Britten and Pears also loved dogs—not just any breed but, like Rostropovich, the smooth-haired miniature dachshund. Britten’s first dachshund, Regency Clytie of Alderney, was the granddaughter of champions, entered the Britten/Pears home and totally captured their hearts. “Our lives are completely changed now,” said the composer about Clytie. When she had puppies, Britten claimed that “even their puddles are adorable.” With the clear intent of keeping out unwanted visitors, Britten and Pears placed signs on their property in several languages reading “Beware of Dog.” Rostropovich added his own hand-painted sign—in Russian, of course.

Rostopovich’s ties to his homeland remained frozen for the better part of his life. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, during the presidency of Mikael Gorbachev, he flew to Berlin on a private jet from Paris and joyfully played Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites all night in front of the Wall. The next year his and Vishnevskaya’s citizenship was restored. Rostropovich died at age 80 on April 27, 2007, some years before his wife, and was mourned by the world of music. His three beloved composers had long preceded him in death, yet he had expressed the certainty that he would meet them in heaven.

One can imagine Rostropovich in that celestial realm, a paunchy man with a fringe of white hair around his bald head, sparkling blue eyes framed by severe black-framed glasses, and an angelic smile on his face. His elegant hands, with the long, tapered fingers, would be resting on that 1711 Stradivarius cello, and his favorite musicians would be in attendance: Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Britten and, of course, the pianist, Pooks.

Copyright 2021 Diana Burgwyn

Categories

Special Features