The True Believers of Giordano’s Rarely Performed ‘Fedora’

By Scott RoseOn December 31, David McVicar’s new production of Umberto Giordano’s “Fedora” opens at the Metropolitan Opera. The controversial work has not been performed there complete in 25 years. Yet, many alluring facets of “Fedora” make the opera a most inspired New Year’s Eve choice.

The second act’s opening party sequence, for instance, includes a grand waltz danced in Fedora‘s lavish Paris ballroom, light-hearted banter between international diplomats and the flirtatious Countess Olga, and a recital by an onstage pianist, Lazinski, vaunted as the “nephew and successor to Chopin.” “Fedora” additionally is very concisely structured, allowing its verismo lead soprano and tenor to leave everything they have on the stage — audiences fervently cheering — without substantially endangering their instruments.

Nevertheless, particularly outside Italy, “Fedora” survives at the fringes of the standard repertoire, often dismissed by critics as “thin,” “hokey,” and “not a masterpiece.” To be sure, another contingent of commentators believes “Fedora” is underrated.

Love or abhor this opera, though, “Fedora” is endowed with a richly fascinating cultural history unknown to most in the English-speaking world, as the source materials have neither been translated nor gathered in one place.

A Point of Pride

It is of no small consequence that Giordano, native to Foggia, was born and raised in southern rather than northern Italy. Given the historical rivalries between the north and south, Giordano’s successes were, and are, a point of pride for many southern Italians.

Prominent among them is the Naples-born maestro Riccardo Muti, who toured Italy in early 2020 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. When the New York Times asked Muti to cite five minutes that will make people love opera, it was not mere happenstance that he chose “Un dí grave; all’azzurro spazio” from Giordano’s “Andrea Chénier.” But in each city of his tour, Muti offered an encore of the “Intermezzo” from the second act of “Fedora.” That excerpt movingly evokes the protagonist’s crucial psychological moment. It does so by deftly recombining various of the opera’s motifs, including the tenor Loris’s lyrically urgent declaration of love to Fedora, “Amor Ti Vieta.” The meaning of that, in full, is “Love, itself, makes it impossible for you not to love me!”

Explaining his selection of this “Intermezzo” to a warmly appreciative public in the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, Muti said “I am Italian 100 percent, but southern Italian 200 percent. The composer of this piece is from the Kingdom of Naples. And to paraphrase an aria from his ‘Fedora,’ ‘Love, itself, makes it impossible for us not to love this city.'”

In 2014, when the Teatro Umberto Giordano reopened in Foggia after eight long years of restorations, Muti did the honors, leading his Luigi Cherubini Youth Orchestra, which serves as a bridge for post-graduate conservatory students into professional orchestras. An elegantly appointed reception room within the Teatro Umberto Giordano, the Sala Fedora, today boasts a piano that once belonged to Giordano. Foggia is also home to the prestigious Umberto Giordano Conservatory.

In 1956, an Italy-wide call sought proposals for a monument to Giordano to be placed in the center of Foggia. The commission went to sculptor Romano Vio. Today in Foggia’s well-peopled Piazza Umberto Giordano, Vio’s resulting bronzes enliven the city’s pedestrian precinct with a positively Felliniesque display. The monument features a wide circular gathering of sculptures of characters from no less than seven Giordano operas: “Andrea Chenier,” “Siberia”, “Marcella”, “La cena delle beffe,” “Il re”, “Mese Mariano”, and of course, “Fedora.”

Before this extraordinary assemblage of his creative offspring, up on a podium conducting them, Umberto Giordano stands, debonaire, self-confident, immortalized. An online video from 1962 shows a press of dignitaries around Giordano’s son as he unveils the elevated statue of his father.

Piazza Umberto Giordano, Foggia

An Arch Over Much of Giordano’s Life

The materials of “Fedora” form an awe-inspiring arch over much of Giordano’s life. In 1885, as an 18-year-old student in Naples, Giordano was thunderstruck by a performance of Victorien Sardou’s play “Fedora” with Sarah Berhardt. The next day, Giordano was already at the piano, experimenting with ideas for an operatic adaptation. And he actually wrote to Sardou, seeking rights to the work. The world-famous playwright responded to the eager youth with “Eh, bien! on verra plus tard.”

For more than a decade, the budding composer remained obsessed with setting “Fedora.” Yet Sardou drove a hard bargain, relenting only after Giordano’s immense success, in 1896, with “Andrea Chenier,” championed by Gustav Mahler, who later brought “Fedora” to the Vienna Court Opera.

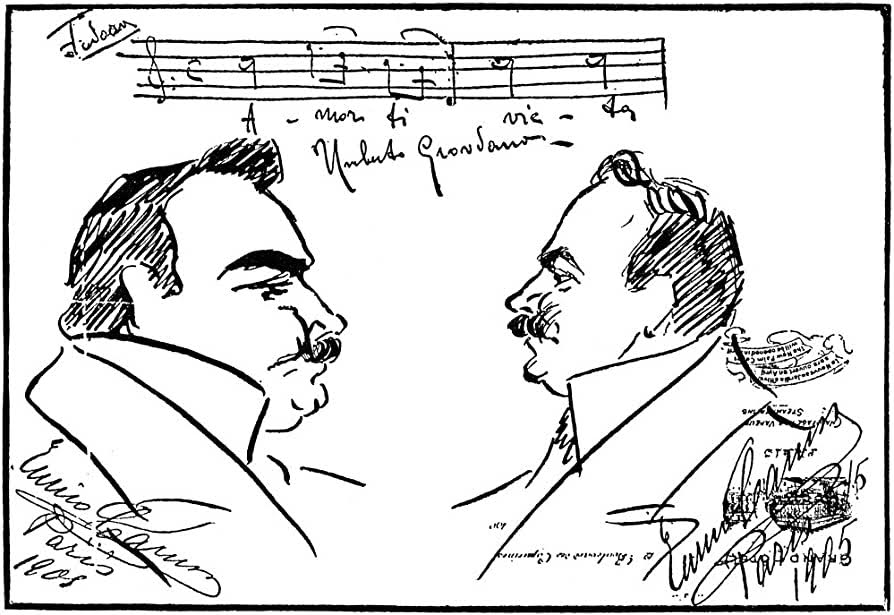

Think what it means that Mahler and Giordano met in person and discussed “Fedora.” Massenet and Saint-Saens, as well as Sardou, expressed admiration for this Giordano opera after its Paris premiere in 1905. For that occasion, Caruso drew a caricature of himself in profile facing Giordano, notes to “Amor ti vieta” on a staff above them.

Librettist Arturo Colautti distilled Sardou’s play to a certain verismo essence, tightly wording the various dramatic narrations while, in places, providing for a thrilling vehemence of utterance for the characters and their emotions. “Fedora” has elements of a giallo, a detective story, intersecting with a tragic romantic trap that Fedora heedlessly lays for herself. Joyously betrothed to Count Vladimir Andrejevich, but crestfallen when he is assassinated in unexplained circumstances, she vows on a Byzantine cross, inherited from her mother, to avenge his death. Setting aside her suspicions that the murderer is Count Loris Ipanov, the better to catch him in a confession, she falls in love with him, setting him up in complex ways that lead to the deaths of his brother and mother in Russia.

As grim reality has it, though, Loris killed Vladimir in self-defense after catching him in flagrante with his wife Wanda. Fedora can forgive Loris, but not herself, and drinks poison from her cross before lamenting that she wants a little more love, though love is unfair, and death is beautiful. Receiving Loris’s forgiveness, Fedora expires.

More than one dozen secondary characters each can seem indispensable and welcome — when performed by top-notch singer-actors — as demonstrated even by a German language recording of “Fedora” with the role of Dimitri taken by one Christa Ludwig.

Giordano was intent on having as his first Fedora Gemma Bellincioni, already world-famous as the first Santuzza in Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana.” He was equally keen on having Bellincioni’s husbandRoberto Stagno as the first Loris. Tragically, Stagno died. And Giordano wasbewildered by suggestions that the insufficiently formed Enrico Caruso should take his place.

In training sessions, Giordano was extremely exacting with Caruso. We can appreciate that the verismo composers of the Giovane Scuola were working together with singers of their day, forging new ways of rendering the human voice expressive. Giordano’s writing for and coaching of Caruso in “Fedora” were milestones on the way to Caruso’s creation of Dick Johnson at the 1910 premiere of Puccini’s “La fanciulla del West.”

Enrico Caruso’s caricature of himself facing Giordano, notes to “Amor ti vieta” in score above them

Giordano himself conducted the November 17, 1898 premiere of “Fedora” at Milan’s Teatro Lirico. Public enthusiasm brought him out for 15 curtain calls. Italian critics were ecstatic. After rapturously singing the praises of the composer, the librettist, and the performers, Il Corriere della Sera said: “Let us rejoice for our country.” Giordano received generous offers to appear in the Americas, but never did, as he was fearful of transatlantic travel.

It has been said that “Fedora” made Caruso, and Caruso made “Fedora.” When the work was first performed at the Metropolitan Opera in 1906, a New York Times critic was almost resentful that anybody had dared to touch Sardou’s original. He nonetheless reported that there was a full house, and the opera had “deeply stirred the listeners.” Further, he wrote that Caruso and Lina Cavalieri as Fedora so excited the audience with the end of the second act that they were called before the curtain several times, overwhelmed with flowers, and so repeated their prior scene.

In 1909, Giordano inherited from his father-in-law a historic property in Baveno on Lake Maggiore which he christened as Villa Fedora. Even today, its adjacent gardens are graced with a Villa Fedora Kiosk that in season sells refreshments and distributes information about Umberto Giordano as well as current cultural events.

The Villa Fedora in Baveno, Italy

Many have remarked movie-like elements of “Fedora,” and Giordano separately did enthusiastically follow the nascent cinematic arts. In 1942, Cinecitta came calling; Giordano contributed new music to, and conducted the soundtrack of Camillo Mastrocinque’s film adaptation of Sardou’s “Fedora.” The composer is credited as “His Excellency Umberto Giordano.”

Often involved with new generations of performers reviving his “Fedora,” Giordano passed away November 12, 1948. Il Corriere wrote about his death in high verismo style. Agonized by fevers, he raised his hands to his temples and exclaimed to his wife “My God! Such suffering!”

Thousands gathered grief stricken outside La Scala, where the orchestra played the “Fedora” Intermezzo. There is video of Giordano’s funeral, the streets thronged, clergy in V formation marching towards the Duomo in front of his flower-bedecked coffin, pallbearers outfitted regally. In attendance, the mayors of Milan, Foggia, and other Italian cities, the Commissario of La Scala, and Giordano’s friend the composer Francesco Cilea. A contemporary television report about Giordano’s death says “In the streets, people point him out and speak his name with veneration. He is one of the glories of Italy.”

History’s Reception

We are fortunate to have legendary Fedoras on recordings; Gilda Dalla Rizza, Maria Caniglia, Renata Tebaldi, Magda Olivero, Mirella Freni. In comparative listening lies a wealth of pleasure. Lamentably, no recordings have yet turned up of Maria Callas as Fedora, though she did perform the role at La Scala in May and June of 1956 with Franco Corelli as her Loris. For Il Corriere della Sera, Italian Nobel Prize winner Eugenio Montale wrote vividly and informatively about that production.

Callas and Corelli performed “Fedora” under the baton of Gianandrea Gavazzeni, who in 1968 published a seminal Italian-language essay “The potential for more serious analysis of Giordano’s music.”

There are many more recent Italian contributions to this intellectual ferment. Michele Girardi published “Fedora, a prima donna on the verge of a nervous breakdown.” In his “The musical language of ‘Fedora‘,” Virgilio Bernardoni persuasively analyzes how Giordano’s uses of musical reminiscences compares to, and in places differs from Puccini’s employment of them. And, included among Agostino Ruscillo’s penetrating observations of this score is his insight that the three orchestral iterations of Loris’s love music occur in C-major, E-major, and G-flat-major, outlining a tritone, the medieval “Devil in music,” its inherent unstable dissonance speaking to the protagonists’ ill-fated love.

Auspiciously, Maestro Marco Armiliato, leading the Met Opera’s performances, is a “Fedora” true believer. In association with the recent Mario Martone production of the opera at La Scala, Armiliato made a promotional video communicating his heartfelt advocacy for the work. And his contributions were nearly universally praised. Writing for Opera Click, Ugo Malasoma went into no small detail explaining the virtues of Armiliato’s interpretation, ending with: “No ifs, ands, or buts; this is beautiful music making.”

Categories

Special Features