The Baritonal Crown – Baritone Željko Lučić On His Beginnings, Favorite Roles & Keys to Success

By Dejan VukosavljevicBaritone Željko Lučić was born in Serbia, in a small town of Zrenjanin, northeast of the capital Belgrade. For anyone familiar with the looks of historical small towns in the countries of the Western Balkan, this is a significant fact.

“Yes, my hometown is indeed a small one, but also an absolutely wonderful place,” Lučić, smiling, told OperaWire in a recent interview. “It harbors a very beautiful architecture of historicism, and you could see wonderful buildings everywhere, those imprints of a great and rich historical heritage. Basically, Zrenjanin is a very rich environment, in every way.”

The baritone noted that his attachment to his hometown is furthered by the “great childhood and fantastic youth” that he experienced with a “family full of love.”

“I had everything that I wanted and needed,” he added. “It was a carefree youth, basically. My personal attachment to Zrenjanin is still very intense, and I tend to go back to Serbia and my hometown whenever I can.”

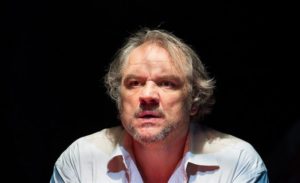

As he continued talking about his hometown and childhood, it was impossible not to notice the increasingly warm smile on Lučić’s face.

Among the nurturing aspects of his upbringing was the music in his home. His parents while not having formal musical education, loved to sing and had “natural talent.”

“By listening to them I had the opportunity to learn some songs as a child,” Lučić revealed. “And then I started to sing. Usually during some celebrations, like birthdays, or weddings – I used to sing. I loved to sing. It seemed all so natural for me.”

A Good Scout Appears

Lučić attended the “Vuk Karadžić“ Elementary School in his hometown, where he was active in musical culture classes. But it wasn’t until famed Professor Slobodan Bursać, the Choir Master of the Choir “Josif Marinković” in Zrenjanin, came into the picture that things really shifted.

Bursać would routinely circle around schools in Zrenjanin looking for young talents. One day, he came to Lučić‘s school and asked the music teacher if she could recommend some young pupil for the choir.

She pointed her finger at the baritone.

“I owe Professor Bursać my eternal gratitude for everything. If it had not been for him, my operatic career would not have happened,” Lučić explained. “He was so persistent. And he never gave up, even in those moments when I simply did not have any plans about my future in the field of music.”

While Bursać encouraged Lučić to pursue a career in music, both knew that the baritone had no formal training. And they knew that he needed it fast.

To Belgrade to Novi Sad

If Lučić wanted to really become a professional singer, Zrenjanin was never going to provide the adequate environment. He needed to go to Belgrade where he would have to start from scratch.

In the big Serbian capital, another Guardian Angel took over – Dorotea Spasić, the renowned professor of singing at the Music School “Josip Slavenski.”

Under her tutelage, Lučić managed to finish both Primary and High Music schools in only four years, and he was ready to enroll with the Faculty of Music.

Still, Lučić saw himself as a choir singer, but not an opera soloist.

“You know, it is difficult to consider a profession where you have zero chance for mistake and you have to be always 100 percent aware of yourself. Perform in front of a huge audience. I was not thinking about it at that moment,” the baritone added.

But Spasić refused to give up on the young singer’s soloist career.

“Please don’t! You can do much more with your voice, don’t throw that away,” she told Lučić. And then she arranged a private audition for the young baritone.

His new mentor? Mezzo-soprano Biserka Cvejić, who regularly appeared on the biggest opera stages in the world, including the Metropolitan Opera House, Teatro alla Scala and Wiener Staatsoper.

Lučić joined the Voice Studio of Professor Cvejić at the Academy of Music in Novi Sad in 1991. Cvejić became his primary teacher and mentor, and in less than two years studying with her, he was offered a contract with the Serbian National Theatre in Novi Sad. It would snowball from there.

Lučić made his debut in Novi Sad in the role of Silvio in Leoncavallo’s opera “Pagliacci” and in 1995 he joined the ensemble of the National Theatre in Belgrade and won the International Music Competition in Bečej. In 1997 he won the first prize at the Francisco Viñas International Singing Competition in Barcelona.

“I had a wonderful time working with Professor Cvejić and I learned a lot from her. She really did a great job preparing me for the continuation of my career,” added Lučić.

And while his career was looking up, Lučić was ready for a new challenge and left his country to expand his professional horizons.

All Roads Lead From Frankfurt

Lučić decided to take the German path, and auditioned to become an opera soloist at the Frankfurt Opera.

“It was the most striking moment after the audition ended,” Lučić narrated excitingly. “General Director of the Opera in Frankfurt Udo Geffe came to me and said: ‘You are exactly the singer we’re looking for. And we need a Verdian baritone.’

“And you see, I have taken that way of singing from Belgrade and Novi Sad. Verdi’s way of singing. I was really a Verdian baritone, my technique was speaking for itself,” Lučić explained. “And I couldn’t have been happier. I was offered a soloist post at the Frankfurt Opera immediately after the audition.”

Lučić signed an initial contract with the opera house and had it extended several times. However, Frankfurt opened up more opportunities for him.

“Intendant of the Frankfurt Opera at that time was Berndt Loebe, Choir Master Alessandro Zuppardo, Head of the Accompanist Felice Venanzoni. Also, conductor Paolo Carignani arrived soon as the new Chief Conductor. This all couldn’t have been better. I had so many Italians around me, taking care of the Verdian baritone in me, leading me the right path. It was fantastic,” Lučić enthused. “I had been given many opportunities in Frankfurt. I sang a very broad repertoire.”

And then, he started to make his first guest appearances in numerous other German opera houses including the Semperoper Dresden, Theater Bonn, Staatsoper Hamburg, Oper Köln, Staatsoper Berlin, Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich.

But then came his debut at De Nederlandse Opera in 2002, with the roles of Guy de Montfort in “Les vêpres siciliennes” and Marcello in “La bohème.” Then came the role of Conte di Luna in “Il Trovatore” at the Teatro Comunale in Florence in 2003.

Lučić also made a high profile debut at the Wiener Staatsoper in 2002, in the role of Giorgio Germont in “La Traviata.”

Meanwhile, the Oper in Frankfurt, seeking to nurture and prepare Lučić with those big debuts, incorporated several of these operas into its own repertoire, thus mirroring Lučić‘s guest appearances.

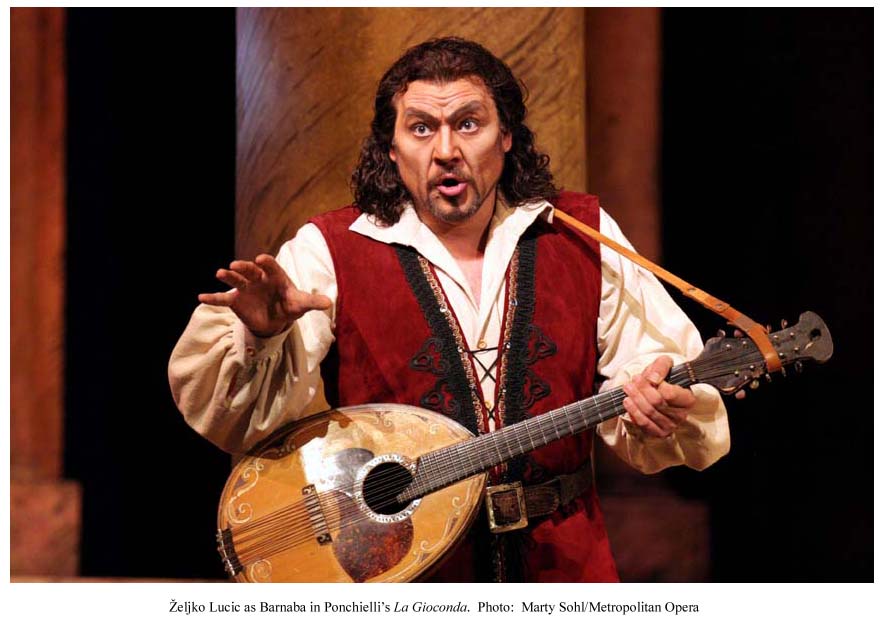

“Short time before my debut at the Metropolitan Opera House in 2006 in the role of Barnaba in ‘La Gioconda,’ I had a concert performance of ‘La Gioconda’ in Frankfurt. That was simply fantastic. Similar things happened with ‘Il Trovatore’ and ‘Rigoletto,'” Lučić further elaborated. “I have only the biggest gratitude for the Oper in Frankfurt, and each and every time they invite me to perform in Frankfurt, I go. And I will always go.”

Baritone’s most recent guest performances at the Oper Frankfurt include title roles in Verdi’s “Falstaff” and “Rigoletto,” as well as Giorgio Germont in “La Traviata.” A production of “Rigoletto” in 2018 at the Oper Frankfurt was special, as it came 10 years after Lučić’s role debut.

After Lučić‘s debut at the Metropolitan Opera House in 2006, it was clear that he was going to grace biggest opera stages with his voice. The Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Opéra de Paris, Teatro alla Scala, Wiener Staatsoper – Lučić‘s career exploded in many directions.

Deep Immersion in Evil

One of the unique aspects of the opera singer’s life is the repertory. Most actors can focus on one role at a time, but in the case of the singing actor, they need to manage a handful of roles in one year, sometimes two at a time.

Lučić, who is in constant demand for many of the top baritone roles, not only has to take on operas that he is very familiar with like “Rigoletto” or “Traviata,” but has to pull back into his repertory bag to take out some operas he hasn’t done in many years.

“There are so many things in this profession that naturally lead one to another,” Lučić began. “So, the text we have to remember is necessarily associated with some specific move, or a gesture on the stage. And that is connected with a specific way of singing. Basically, that is one mechanism that runs smoothly at all moments, in all directions. The key is, again – the experience. After many times, those moves, notes, gestures… Become deeply engraved in memory. Very, very deep memory. It is like one big machine in the back of my head, rotating the movie slides – and when I need one, I just grab it. And it is there, immediately.” adds the baritone.

He added that roles he does consistenly like “Rigoletto” or “Scarpia” might take him a few hours to recall.

“How do you think that last minute calls work, anyway?”

Speaking of Scarpia, there is no doubt that it has become one of his major go-to roles in recent years. What is unique about the character and especially from the perspective of a baritone is that he is a pure monster, a challenge that is not often associate with either tenors or sopranos. While those higher voice types might take on monstrous characters once in a while, the baritone is constantly faced with becoming an antagonistic force onstage.

In the case of Lučić, he has become associated with such characters as Iago and Barnaba, but Scarpia presents its own unique challenge.

“Scarpia is a murderous evil. Thus, it is very difficult to portray that character on stage. But psychology teaches us that we all, very deep within us, have some potentially unwanted, harmful drives and urges,” Lučić noted. “Good mental control keeps those urges at bay. But when I am on stage, I am trying not to act. My goal is to wake up those deep urges within me, and simply be myself, Željko Lučić, in Scarpia’s shoes. Reacting the same way as he would, should I find myself in the same position. Psychologically connect with him. And I always ask myself: what would I do if I were in Scarpia’s place?”

He noted that this approach can be mentally exhausting but it is impossible to approach the task of playing a villainous character in any other way.

“For example, Barnaba in ‘La Gioconda’ for my Metropolitan Opera House debut in 2006 had just those horrific traits,” he added. “And it was my big debut. I had a huge responsibility to give the New York audience the horribly cruel, murderous Barnaba. You could call this acting. But for me, there are more dimensions to it. I am working off those evil emotions and urges onstage, and let them activate.”

Where most singing actors are constantly looking for new details in the score and in the text to further their immersion in the character, Lučić‘s feels that overthinking things can take away from its unique spontaneity.

“Obviously, the process of character building is very long and demanding, like carving the sculpture. At one point adding more details much more hurts than helps,” the baritone added. “After 100 or more performances character is built to the degree that adding more details tends to diminish the quality of the performance. The way we sing anything on stage, body language, that is all the part of that huge puzzle.”

Rigoletto, or The Verdian Crown

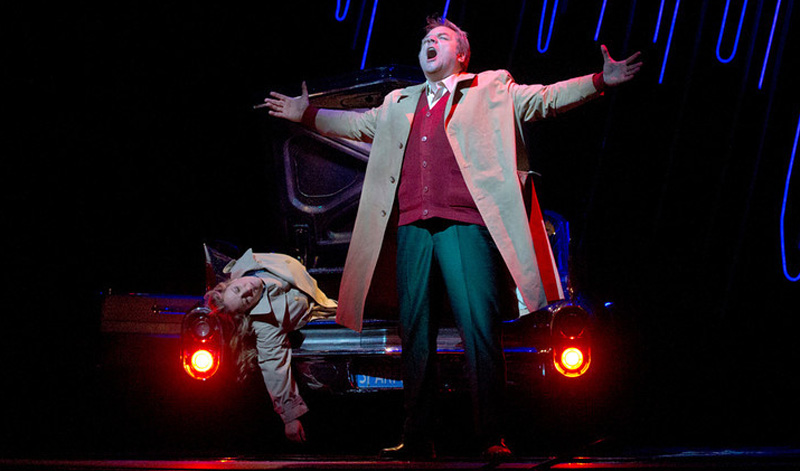

Another role that has brought Lučić worldwide fame and recognition is that of Rigoletto. The baritone has portrayed the Verdi’s Court jester over 100 times, with the initial performance taking place at Semperoper Dresden in 2008 with Juan Diego Flórez and Diana Damrau.

“You know, I was really patient with the role of Rigoletto. I was waiting for a long time to do it. I just felt that I was not ready enough. It was growing in me for many years,” Lučić stated. “And when it finally came, it felt really great. An all star cast, with Diana and Juan Diego, it just couldn’t have been better.”

Since then he has performed the role at all the major theaters including the Metropolitan Opera (29 times as of 2020), Teatro alla Scala, San Francisco Opera, and Opéra de Paris. He noted that in 2011 alone, he performed the role over 60 times. And he has a lot more “Rigolettos” coming his way in future seasons including 14 in Paris this June and July.

“For me, Rigoletto has always been the crown of baritonal singing,” Lučić added excitingly. “In order to find out the limits of his own capabilities, every baritone should sing Rigoletto. And Rigoletto also brings immense joy to the singer. It is a never-ending story.”

“In the First Act, that unhappy fool is having a dialogue with himself, an inner dialogue, during ‘Pari Siamo.’ He is asking himself, how will it all end? Then his daughter Gilda appears. And that is the beginning. It is unfolding quickly, with series of fatal events.”

He noted that each of the opera’s acts requires a “different baritone, a different way of singing.” For the first Act, the baritone must be a court jester while the second demands he be poor, abandoned, and alone. Finally, the third Act is about vengeance.

“Rigoletto also brings all those mixed emotions to the surface, explores distant limits of inner psychology. And don’t forget, his job is to be mean. To ridicule other people. In the end, it is just a massive tragedy hitting. He practically kills his daughter, and attributes everything to the curse. But the curse is actually himself.”

(Credit: Metropolitan Opera / Ken Howard)

The Way To The Top

It has been said many times that operatic singing is an athletic discipline. In order to achieve a top notch performance, every singer simply must obey certain rules. For Lučić, the first and most important of these is vocal rest.

He noted that he is extremely disciplined about protecting his voice after a performance. He might sign autographs for his fans and take pictures, but after that backstage activity he heads straight home to the apartment or hotel where he is currently lodged.

“My vocal cords have been already irritated at that point, and any additional unnecessary talking would just make things much worse,” he noted, emphasizing that he isn’t one to go to post-performance parties or hangouts. “And during huge runs, I usually have only two days, three days at maximum, before the next performance. My voice needs a rest at those times. I respect that routine religiously. Yes, it comes with a cost. Maybe I’d feel alone, but I have my commitment to the audience. To opera houses. There is no compromise regarding that commitment.”

Another major key for him comes down to one value he learned from Spasić back in Belgrade – patience.

“In order to achieve anything in the world of opera, a singer has to be very patient. Always has to wait for the right moment, and when it comes, grab the opportunity with both hands. But not before. As Michelangelo once said – Genius is eternal patience,” Lučić noted, smiling. Always smiling.