Teatro Real de Madrid 2019-20 Review: Die Zauberflöte

Stanislas de Barbeyrac & Olga Peretyatko Shine in Kosky & Andrade’s Lifeless Production

By Mauricio Villa(Credit: Javier del Real)

The Teatro Real de Madrid kicked off 2020 with a revival of the successful production of “Die Zauberflöte” by Barrie Kosky and Suzanne Andrade-Paul Barrit, which was last seen in 2016.

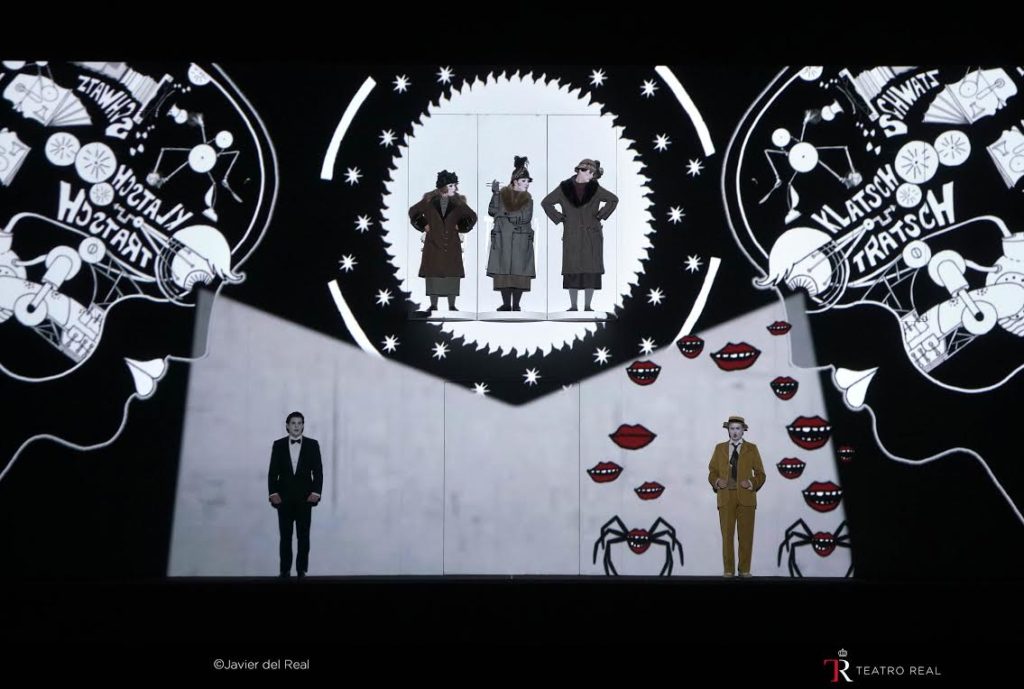

The staging is meant as an homage to silent movies and there are no sets, just a big white screen very close to the edge of the stage that has several revolving doors across two levels: one on the stage level and five situated in the middle of the screen through which characters appear and disappear as they turn. The high-level doors possess small platforms on which the performers must sing practically still. In addition to projections shown throughout the performance, there is also a very striking choice to eliminate the dialogues of this Singspiel and turn them into large titles onscreen while a pianist (on this evening, Ashok Gupta) accompanies the images with fragments from Mozart’s “Fantasy in C minor.”

Attractive But Lifeless

The concept is attractive, new and luminous; some scenes like Tamino running away from the big snake at the beginning are fascinating; here we see the top of the tenor’s body “running,” while fast running legs are projected from his waist below. The singers interact with the images projected, like owls, birds, arrows… which turn their work on stage into a precise coordination with the lighting and videos. The results are meticulously choreographed and the videos are very inventive.

And yet, it was not overly convincing. Despite being an attractive idea, there is no evolution and after 20 minutes, it becomes tedious. The video creations have a cartoonish design, clearly intended to appeal to a younger audience. But even then, there are moments where it simply doesn’t match up tonally (cabaret dancers in lingerie under the singer’s heads in not child-appropriate). Moreover, it feels rather lifeless and you often find yourself wondering if you are watching a video game unfold before you. The singers themselves never really feel like they are inhabiting characters more than they are going through motions as required by the projections. The people of this opera come off as mere puppets.

This empty feeling is only accentuated by the lack of dialogues that would give the characters personalities. Moreover, it would be appreciated if these projected phrases would have been translated into Spanish (or the native language of where the opera is performed) rather than keep them in German. Instead, you find yourself reading subtitles instead of engaging with the stage.

Of course, this is but one opinion, as it seemed that, based on the sold-out run, the audience found a lot to enjoy.

A Major Surprise

French tenor Stanislas de Barbeyrac was a surprising revelation in the role of Tamino. He has a dark rotund voice with an unbelievable volume and projection, something which is very rarely found in this kind of repertoire. I would classify his voice as a pure lyrical tenor, even with a tendency to be a lirico-spinto. He has specialized in Mozart and baroque repertoire having sung roles like Idomeneo, Don Ottavio and Tamino in theaters like The Royal Opera House in London and The Metropolitan Opera House in New York. Therefore, despite of such an unusually big voice, he has perfect control of Mozart’s style which implies a purity in the vocal line, a clean attack of the notes and intervals, the use of dynamics like diminuendos or whole phrases, and the ability to sing comfortably in the passagio most of the time.

His first short entrance “Zu Hilfe! zu Hilfe!” showed off his potent voice, with incredibly sonorous Gs and A flats. But it was during his first aria “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” where he truly shined, the tenor dominating his big voice with proper style. After a clean forte attack of the first G and A flat of the aria, he sang an exquisite mezza voce line on “Mein Herz mit neurer regent füllt.” This is a very difficult aria to sing as the voice is really exposed because of the soft orchestration and the obsessive writing in the passagio.

He seemed to struggle a bit with the forte A natural on “Hierent-sprang” which was unstable and nearly broke. However, his subsequent solo Andante with the flute, “Wie starkest nicht dein zauberton,” was impeccable and the several A naturals were rotund and secure. His voice sounded menacing during the fire/water challenge, and he was perfectly heard over the rest of his colleagues in the second act Quartet with Pamina and the two-armed men.

Papageno was portrayed by the German bass-baritone Andreas Wolf. He has an attractive timbre and decent projection, but his singing was so irreproachable that his performance seemed a bit static and one-dimensional. This role was composed for Emanuel Schikaneder, who wrote the libretto and the original staging. So, the writing of this role is quite manageable regarding the tessitura and he mostly sings quick lines to contrast the more lyrical arias other characters perform. This means that the weight of the role lies in its interpretation, and unfortunately his two arias “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” and “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen,” as well as his duet with Papagena “Pa-Pa-Pagena,” didn’t really add much flavor to the performance.

Fortunately, of all the characters, Papageno is the most defined in the production. He is intended to be a recreation of Buster Keaton and Wolf made a decent imitation of this mythic figure from the “cinema silent era.” However, his gestures were too small and it seemed as if he was truly acting for a camera rather than a big opera house. If he had made his reactions and gestures bigger it would have reached the audience and created far more laughter than was heard during his appearances.

Revelations

The internationally recognized Russian soprano Olga Peretyatko sang the role of Pamina. This lirica-leggera soprano, who has been struggling in her highest register lately, found in Mozart’s composition the perfect vehicle to demonstrate her depurated phrasing and legato singing. Her sweet timbre was darkened and the tessitura seemed to be rather comfortable for her.

The highlight of her performance was the interpretation of her second act aria “Ach, ich fühl’s” which she sang with delicacy and emotion, reaching the several high B flats effortlessly and even interpreting the chromatic staccato ascension to this note pianissimo on “Her zen mehr zurük!” Her voice shone beautifully in the aria.

The rest of Pamina’s appearances are short lines or within the context of an ensemble and Peretyatko managed to maintain a sense of ease and vibrant vocal production. She did her best with the staging but once more her character was not well-delineated which drives you to pay more attention to the projections, the voice, and the music than the acting.

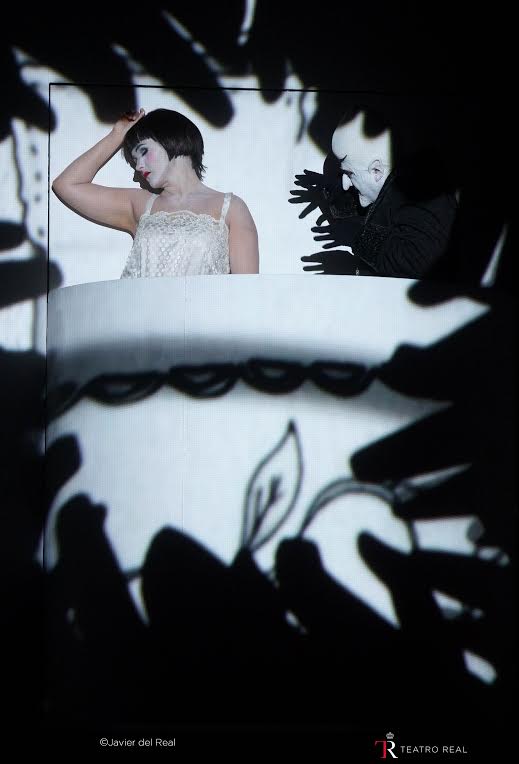

Polish soprano Aleksandra Olczyk, who portrayed The Queen of the Night, was another revelation because as it happened with the tenor, she has an unusually dark and big voice which is not common in such a stratospheric role.

When she began the slow part of her first aria “O zittre nicht,” which is very central, she sounded like a pure lyric soprano with a velvet quality and fair vibrato. Her voice grew as she rose up with the two A flats sounding particularly round and full. I found myself wondering how she would managed to sing the Allegro part of the aria with all the coloratura and high notes. However, her coloratura was clean and impeccable and her voice kept growing in size and projection while reaching the several high Ds and Cs. She also managed to hold the high F a few seconds rather than the usual staccato short note that most sopranos do.

Her interpretation of “Der hölle rache” sounded vengeful and menacing thanks to the qualities of her voice. She managed to sing the staccato high Cs with an unusual force and power and really matched the intentions of the character. All the high Fs were perfectly in pitch and rhythm, keeping all the staccato sections completely balanced in volume and metric.

She was exceptional in the staging as she had to sing the arias with her whole body covered by a plank over which a projection of her spider body was shown. Only her head was visible, so she had to sing completely still with her arms close to her body. That’s a very hard task to manage, especially when singing so many coloratura and stratospheric high notes. She was obviously one of the most applauded singers of the night, and she deserved it.

Italian bass Andrea Mastroni sang Sarastro. He has a rotund basso profundo sound, something which made him shine in his second act aria “Oisis und Osiris,” a piece which goes from low F to high C in the bass register. His vocal line was smooth and the attack of the notes direct and effortless, which is harder in big voices.

His second aria “In diesen heil’gen” maintains the same vocal pattern, with a tendency toward the lower part of the voice and slow floating tempo. Again, Mastroni sang it masterfully. In the terzeto with Pamina and Tamino he reached the high E flat effortlessly.

The interpretation of tenor Mikeldi Atxalandabaso as Monostatos was brilliant. A Teatro Real regular, his voice production is excellent, his timbre so insinuating and his projection so seamless that you always wonder about him in principal roles. His single aria “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden” was amusing and impeccable. His character was strongly defined as Noferatu, and Atxalandabaso gave a masterclass in portraying this famous silent era vampire, under a heavy and probably uncomfortable characterization with a splendid body work and big convincing movements and gestures.

Elena Copons, Gemma Coma-Alabert and Marie-Luis Dreben were exceptional as the three Ladies. Their voices melded sweetly in synchronization.

The resident musical director of Teatro Real Ivor Bolton conducted the reduced orchestra as the true Mozart expert that he is. He presented a lively determined overture and always found a solid balance between the different orchestral sections. He was always in perfect communion with the singers, choosing moderate tempi to facilitate their interpretations. There is for example a tendency to choose slow tempi for Tamino’s portrait aria or frenzied fast ones for The Queen of the Night arias, making it harder for the singers. But this was not Bolton’s case. Then again, as the whole cast, he had to synchronize the orchestra with the projections, making his job harder, but he succeeded in giving an amusing, inspired, and moving reading of the score.

Ultimately, the production, despite its best intentions, was rather ordinary in its impact. Fortunately, the opera boasted a solid cast that did justice to the famed Mozart score.