Teatro Massimo 2025-26 Review: ‘Pagliacci’ & ‘Aleko’

By Mike Hardy(Credit: Rosselina Garbo)

Can traditional opera really influence modern society and force it to reexamine its shortcomings? Can it impact the pressing issues of our times? Certainly, the powers that be at the Teatro Massimo opera house in Palermo believe so. And, judging by their opening night presentation combination of two short operas, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s “Aleko” and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s “Pagliacci,” they just might be onto something.

Midway through the performance of the latter opera the house witnessed an astonishing, unprecedented incident. The entire audience, over 1,300 patrons, rose as one to give a standing ovation as the names of 75 women — just some of the victims of femicide who have died at the hands of violent partners in Italy since January 2025 — were projected onto the giant screen onstage behind the two key cast members. In response, the two stood motionless, side by side, facing the audience.

It was an extraordinarily powerful and emotional moment for all, not least for conductor Francesco Lanzillotta who was, very visibly, moved to tears. This rarely seen coupling of Russian and Italian verismo, first staged in 2016 in the United States (“Pagliacci,” of course, is most frequently performed with Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana”), is a first for Teatro Massimo. Despite their entirely different cultures, these operas share a near identical storyline and are staged here in a very specific manner to address the tragically topical issue of femicide.

This new production from the Fondazione Teatro Massimo marks the Palermo debut of director Silvia Paoli whose vision brings these two stories, which focus on the theme of violence against women, into sharp dialogue in the month of November: when the “International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women” is celebrated.

“Aleko,” performed here for the first time in Italy, is Rachmaninoff’s one-act opera, with libretto by Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, based on Pushkin’s poem “The Gypsies.”

Aleko is the name of the Russian man who abandons his society for a nomadic life among a tribe of gypsies and ends up falling in love with a young gypsy woman, Zemfira. Alas, when Zemfira’s passion for Aleko wanes, she takes a younger lover. Consumed by jealousy, Aleko murders both Zemfira and her lover. In an act of mercy that sharply contrasts with the shocking violence he perpetrates, his life is spared by the gypsies, including Zemfira’s father, who instead banish him from the camp, condemning him to a life of despair and solitude.

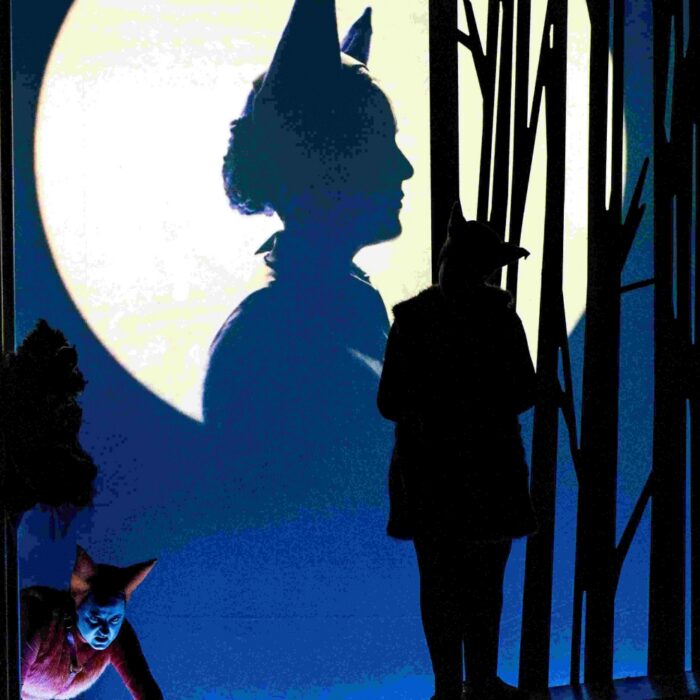

In “Aleko,” the curtain rises on a viscerally shocking display of the titular character raining down a series of knife blows on Zemfira, 75 stabs to be exact — representative of the 75 victims whose names later appear projected onscreen. From the shadows the chorus emerge, appearing almost nun-like in dark gowns and headdresses. Zemfira eventually rises in a blood-soaked gown and slowly wanders around the stage, unveiling (quite literally) the story of her demise by removing sheets and other coverings from the assembled stage props, thus introducing characters and scenes from her story. These include her curmudgeonly father in a roll-top bath with his transistor radio; a Narnia-style wardrobe from whence an entire dance troupe emerges; a lounge settee where Aleko sits, contemplating his failing relationship; the bed where he lies and from where Zemfira secretly absconds to meet her lover and to plan their elopement.

This ‘spirit’ form of Zemfira is played by an uncredited actress who remains onstage near-continuously throughout the entire opera, including being alongside her ‘living’ counterpart. The ‘living’ Zemfira is played by soprano Carolina Lopez-Moreno. However, the unnamed, blood-spattered phantasm waits until the second opera of the evening, “Pagliacci,” in order to give her scene-stealing performance. It is then that she slowly enters stage left to join Lopez-Moreno immediately after the latter’s character, Nedda, receives a vicious beating from her husband, Canio, after he discovers her infidelity with Silvio. This scene underpins the aforementioned presentation of the names of Italy’s femicide victims.

“Pagliacci” is a far more colorful staging than the preceding dimly-lit shadowlands of “Aleko.” There are tumbling clowns, bright pastels, gesticulating children, comedic interactions, frivolous crowds, and slapstick antics galore. But the end result is the same in both tales: love, desire, deception, jealous rage, and murder.

These productions both depict some of the most affecting violence I have ever seen onstage: utterly brutal and undeniably shocking. I have already alluded to the opening scene of “Aleko,” where the actress portraying the ‘spirit’ version of Zemfira is stabbed 75 times, her murderer flipping and rolling her over in order to inflict damage to all areas of her body. This scene is replicated again, albeit to a lesser extent, towards the end of the opera, when her dalliance with her lover is discovered and Zemfira meets her fate. But for me, this particular act of symbolic slaughter pales into insignificance compared with the brutal beating Nedda receives, meted out by Canio in “Pagliacci.” She is first thrown to the ground before being viciously kicked, then struck forcefully in the face, knocking her to the ground again before being further kicked.

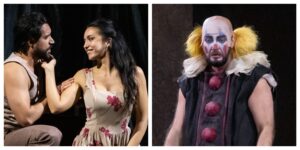

To portray a victim of such horrific violence with any degree of conviction and accuracy is a big ask for any soprano, but to play such a role in two separate operas, sequentially, in the same evening, must surely demand much resilience and fortitude. And in Caroline Lopez-Moreno, the house could not have found a more stellar performer. It arguably requires minimal acting skills to be a murder victim, but to play the victim of a sustained violent attack requires something else. And when Lopez-Moreno was sprawled out on the floor, whimpering, crawling pitifully, and rocking in apparent agony, it was too much to bear and I almost felt compelled to rush to her aid — such was the veracity of her acting.

Her stagecraft here was not just limited to playing a battered victim. Her characterization of bored lover, Zemfira, in “Aleko” was enhanced with a most sensual, albeit bordering on explicit, rendering of sexual feverishness, authentically alluring without being overly melodramatic.

Her Nedda in “Pagliacci” displayed humorous interplay in her abject rejection of Tonio, at first playfully dismissive before having to resort to spirited aggression to repel him. Her faux desires for Beppe were delightfully but innocently coquettish. Her amorousness for Silvio, and her despair at being conflicted in her relationship with him, was completely cogent. Her fear and ultimate revulsion of Canio was almost palpable.

Lopez-Moreno is not just a consummate actress but a gifted soprano with a wide palette of colours, totally expressive, with a voluminous upper register, and capable of melting into deliciously sweet diminuendo. Her duet with lover Silvio was exquisite, her “Negli occhi mi guarda! mi guarda! Baciami, baciami! Tutto scordiamo!” was most enchanting. I consider her to be a superlative talent whose rise to greater stardom will be unequivocal.

Her nemeses came in the form of baritone Elchin Azizov as Aleko, and tenor Brian Jagde as Canio. Azizov puts in solid performances, firstly as the lovelorn Aleko and subsequently as the hapless but nefarious Tonio. His portrayal of an embittered, dejected lover is engaging, if not disconcerting. Singing with a rich, strident tone, his cavatina, “The entire camp is sleeping,” (Ves’ tabar spit), is mournfully impactful, almost eliciting commiseration and empathy. His “Pagliacci” prologue, as Tonio, was characterful and powerful, skillfully delivered while changing into his clown costume. His scenes with Nedda were suitably repugnant and licentious, performed with just the right balance of comedy and nefariousness. Hapless and hopeless, but this Tonio is no fool, and is played to malevolent perfection.

Crazed, murderous clowns have featured in several films and books but invariably as hugely histrionic characters. Brian Jagde’s Canio is a different breed of animal entirely. Dressed head to toe as the troupe’s leading clown, he enters nonchalantly enough to advertise his travelling show, but when he sings of comparing the comically staged romance between Nedda and Beppe to a potential real-life infidelity that he might discover, his entire persona changes tangibly, if not chillingly. So, when he does discover his wife engaged in an illicit entanglement, his brutal beating of her is genuinely perturbing and entirely believable, seemingly devoid of any melodrama. Moreover, he sings with a sublime instrument, a multi-facetted, expansive tenor with stentorian dark, almost baritonal beauty in the lower and mid registers, blossoming into heroic, powerful yet clarion utterances at the top. His rendition of the famous “Vesti la giubba” was so impassioned and heart-wrenchingly palpable, beating his chest during the line “Ridi del duol che t’avvelena il cor!” that it almost managed to engender sympathy — a most astonishing feat given that the victim of his horrific attack was still trying to recover, lying on the floor, during the aria. It received much applause, with several audience members giving him a standing ovation at the cessation of the piece. It is hard to imagine a more gifted and versatile tenor on the stage today, not just for his vocal qualities but also for his remarkable stage presence and acting abilities.

Other tenor roles in the evening’s performances worthy of merit go to Pavel Kolgatin in the role of Zemfira’s paramour, the Young Gypsy, who delivered a captivating aria “Roman molodogo tsygаna” (Young Gypsy Romance), sung with shimmering bright resonance and a Bel Canto-esque beauty. His duet with Zemfira was equally exquisite. Matteo Mezzaro takes on the role of Beppe and produced possibly the finest “O Columbina” aria I have ever heard, which garnered deserved applause from the audience. He sings with a most proficient, sweet, and agile lyric tenor voice. Baritone Gustavo Castillo was more than accomplished in the role of Silvio, and sang with a deep, warm, sonorous tone — winsome yet commanding when pleading with Nedda to escape with him, “E fra quest’ansie in eterno vivrai!,” and divinely harmonious in the passages where they sing together, “Tutto scordiam.”

Special mention must also go to bass Petar Naydenov in the role of The Old Gypsy, Zemfira’s father, who made what must have been one of the most unexpected, if not comical, introductions in an opera. He was tasked with having to sit motionless for some time beneath a covering before eventually being revealed seated in a bath, near naked, clutching a transistor radio. He then delivers his aria which sets the tenet of the whole opera, “Volshebnoy siloy pesnopenya” (The Old Gypsy’s story), a narrative piece delivered with treacle-rich resonance, recalling his own past love for a woman who abandoned him and their young daughter, Zemfira, for another man. Not just a fine voice but a tricky piece of physical maneuvering, rising from the bathtub and precariously stepping out, all the while telling his tale while being towel dried by his daughter.

The Teatro Massimo choir were sublime, delivering an exquisite chorus, especially during “Aleko,” where their glorious voice played a major role in telling the story. The “Choir of White Voices” (the Massimo Youth Chorus) were joyous during the opening scenes of “Pagliacci.” The Dance Corps and Ballet Company of the Teatro Massimo, along with the Jean-Sébastien Colau Dance Corps, provided some visually spectacular modern dance, especially during the extended routine in “Aleko” where their art was essential in developing the story of the Gypsy camp. One particularly impressive routine saw groups of partners, seemingly engaged in courtship rituals, whose movements were brief and staccato-like, as if animated GIFs.

The orchestra were most commendable, especially the string section who produced real magic. They were lovingly coaxed and caressed by conductor Lanzillotta, who was a joy to watch at work, manipulating not only his charges but visibly taking time to guide the onstage singing.

This was not only a musical triumph, but a superb feat of artistic excellence, production-wise. The sets were hugely contrasting yet equally majestic. Designed by Eleonora De Leo, the vibrant color and whimsical carnival staging of “Pagliacci” has already been alluded to — but the real pièce de résistance was her vision for “Aleko.” The simple, gradual introduction of key set pieces, revealed by the wandering spirit of Zemfira by removing their expansive dust covers as if they were long forgotten museum exhibits in storage, brought them to life. It was redolent of those interactive, augmented reality displays one finds in exhibitions. Consequently, lighting designer Marcello Lumaca’s skills were paramount, not only in ensuring that his spotlights isolated and compartmentalized each scene, but also created suitable darkness at the fringes of the stage, facilitating the almost ethereal comings and goings of the chorus as they materialized and dematerialized into and out of the scenes.

In almost all of my reviews, I allude to my maxim that opera is all about the singing and the music. But in this case, that can only ever be a part of the story. The themes, aims, and goals bravely envisioned by the Teatro Massimo team could never be truly achieved by music alone. Perhaps the greatest accolade for this production should be reserved for Director Silvia Paoli, whose brilliant concepts and ideas bring to fruition what, ostensibly, opera alone could not undertake.

Honour killings, or “crimes of passion,” have deep roots in Italian history and law, with legal defenses for such actions only being abolished in 1981. Before the curtain rose on “Pagliacci,” black and white footage of a group of young men was projected onto the backdrop screen. They were discussing in an interview, ostensibly from around the 1960s, the seemingly widespread practise of dispensing of one’s unfaithful partner by violent means rather than by divorce. The nonchalance with which they collectively appeared to find this acceptable was both sickening and hugely unnerving.

Of course, a hard-nosed cynic, perhaps playing devil’s advocate, might suggest that these particular opera characters, Zemfira and Nedda, are not the most ideal poster girls for generating universal sympathy or for promoting the interests of women, given that they augment and exacerbate their infidelities by mocking and effectively humiliating their respective cuckolds. Such a cynic might further opine that basing such a seriously themed campaign on such individuals may be perceived as frivolous and doomed to failure. It is a testament to Paoli’s direction and commitment, along with the Teatro Massimo teams’ vision, that these productions unquestionably succeed.

The careful placing of multiple flowers on the corpse of Zemfira by the invited female employees of the theatre, including the makeup artists and seamstresses from the costume department, at the end of “Aleko,” was profound and heart-rending. This was a tribute from the “women who want to remember that we cannot look the other way, who tell us how much this drama concerns all of us.” Yet there was one, single act that sticks with me: the slow, measured entrance by the ‘spirit’ of Zemfira during the performance of “Pagliacci,” where she sidles up to the broken Nedda, now having managed to find her feet after her brutal assault, and hands her the dress she herself wore in the first opera, along with a stick of lipstick to apply in preparation for the final act. It was an overwhelmingly compelling metaphor that spoke volumes about the realities of violence against women everywhere. It brought the entire audience — and, hopefully, all who see it — to their feet.

Perhaps the words of the Gypsies, when electing to spare the life of Aleko despite his heinous deeds, preferring to banish him from the camp, just might resonate with someone, somewhere, sometime, “We are wild, we have no laws, but we do not torture or kill anyone. We need neither blood nor tears. We have no need of a murderer. Your voice would be unbearable to us.”