Teatro La Fenice 2021-22 Review: La Griselda

Strong Singing Performances Throughout Rescue A Flawed Production

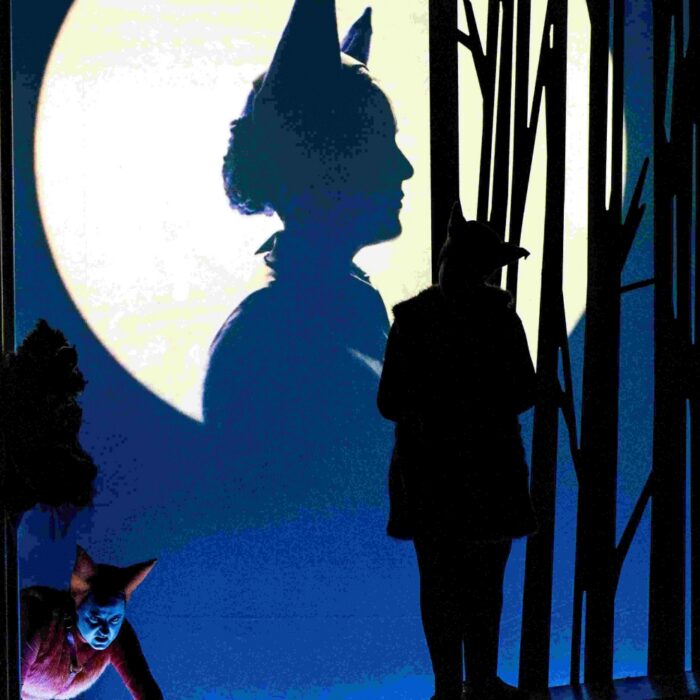

By Alan Neilson(Photo: Michele Crosera)

Given that Venice is the city of Vivaldi’s birth and the scene of most of his musical successes, it is fitting that La Fenice has been one of the leading companies in the movement toward rehabilitating staged performances of his operas. This season’s production of the composer’s 1735 work “La Griselda” will mark the fifth consecutive year in which the company has staged one of his operas. The run began in 2018 with an imaginative and historically informed presentation of “Orlando Furioso,” which captured the work’s dramatic intensity and musical variety, and has arguably been the best production to date, although its staging of “Dorilla in Tempo” in 2019 was certainly the most eye-catching with its beautifully colored sets. Of course, alongside greater exposure comes greater audience awareness and higher expectations, and last year’s unremittingly dark and violent production of “Farnace” fell short of the mark. Unfortunately, “La Griselda” also proved to be somewhat of a disappointment.

Misguided Direction

Much of the blame, although not exclusively so, must lie with the director Gianluca Falaschi, who also acted as the set and costume designer. As a result of a series of misguided decisions, he managed to cloud what was a fairly straightforward, if banal, narrative so that the dramatic thrust of the drama was lost, as the focus shifted to extraneous concerns. More importantly, however, he decided to experiment with the fundamental conventions of baroque opera, which led to the beauty of Vivaldi’s music being sidelined.

The problems started not with Falaschi’s underlying conception, but with its implementation. Having identified the patriarchal system as the fundamental driver for the unfolding drama, which in itself is not an altogether unreasonable position to take, he then decided to shower the audience with examples of how men abuse women. It was done in such a heavy-handed way that hardly a scene was able to pass without a woman being debased or subjected to some form of attack. There was no delicacy involved, no competing motivation was explored, and worse, it was often gratuitous to the point of absurdity. Women were routinely groped, and demeaned. There was a violent and shocking rape scene, in which the victim then wandered around the stage in a state of shock and disorientation. Having a man wander onto the stage to urinate against a tree during an aria by Gualtiero came across as contempt for the audience more than a sign of masculine toxicity.

Such was the director’s determination to portray the range of abuse which men inflict upon women, that he opened the opera in a hall with women working at sewing machines, rather than in a royal palace, purely so that it would open up another avenue for depicting further forms of abuse against women, this time in the workplace. And thus it continued, so that Griselda’s own suffering at the hands of her husband began to fade into a montage of unremitting male aggression, and arguably paled beside the suffering inflicted upon some of the women.

An Experimental Approach Which Failed

In his program notes, Falaschi makes it clear that he finds the da capo aria a hindrance to the drama, stating “ (the da capo) …blocks the time in an act… …I would like to counter this suspension with a narrative continuity…” In other words, he wished to bypass this period of reflection in order to keep the drama moving forward. What should be an opportunity for the singer to take center stage to show off their ability in exhibiting an emotional state was subsumed to wider dramatic concerns, thereby undermining the whole purpose of the aria, and the baroque aesthetic in the process. Moreover, it relegated the position of singer and ignored one of the chief reasons why audiences pay to watch baroque opera. So while Roberto sang his aria “Che legge tiranna” in which he gave voice to his torment at having to lose his lover Costanza to the king, the audience was forced to watch an animated uncomfortable rape scene in the background. The singer was completely overshadowed. Similarly, Gualtiero’s aria “Tu vorresti col tuo pianto,” in which he rejects Griselda yet again, he had the singer compete with a man casually urinating on a tree. Whatever its symbolic references, the image was too powerful to allow the audience’s full attention to rest on Gualtiero.

Falaschi’s divided the opera into two settings. The first part was supposedly set in a palace, but with its bland, unimaginative scenery it could have been the foyer of a cinema, whilst the second part was set in a forest, which at least had the advantage of adding color to the stage. The idea of the forest representing Griselda’s inner space, a place for her thoughts and memories was certainly a good one, but it did appear that this was done primarily to allow Falaschi to bypass the static da capo arias and continue with a dynamic narrative.

There is certainly nothing wrong with Falaschi experimenting with the basic dramatic structure of the baroque opera, but hopefully, this will have sated his curiosity, and he will accept that the approach was not fully successful.

On a more positive note, Falaschi definitely succeeded in keeping the narrative moving forward, and his guidance to the singers in crafting their scenes was successful; their acting was well-paced, convincingly appropriate, and allowed for meaningful interactions.

Fasolis Leads A below Par Performance

As with the past Vivaldi operas at La Fenice, the musical direction was under the auspices of the baroque specialist Diego Fasolis. Unlike past productions, however, in which he elicited vibrant, finely layered, and dramatic readings from the Orchestra del Teatro La Fenice, the performance on this occasion was fairly pedestrian and lacked consistency. The vitality and rhythmic urgency that one associates with Vivaldi were seldom present, and the expected versatility and delicacy failed to materialize so that the orchestral textures often sounded thick and heavy. There were also some coordination problems between the singers and the orchestra, with the singers appearing to struggle for parity. On the other hand, there were passages of excellence that caught the spirit and flair of Vivaldi’s music, for example, Costanza’s aria “Agitata da due venti” was given a splendid rendition in which the strings played with real brio. There was also a noticeable improvement from the orchestra as the evening progressed.

Spirited Performances From All The Singers

The singers all performed well under less than perfect circumstances and were largely responsible for the periods in which the performance rose above the mediocre. They engaged enthusiastically with Falaschi’s direction, and grappled determinedly, with varying degrees of success, to ensure their arias had the right effect. Recitatives were strongly delivered with plenty of detail and emotion, which allowed the characters to develop and interact successfully.

Griselda, One Victim Among Many

Griselda, who is treated with such casual brutality by her husband, should be THE victim of the opera. Unfortunately, by placing her suffering into a context in which all the women on the stage are abused, she is relegated to A victim. Moreover, her plight is no worse than the others, and there is, therefore, no reason to elevate her suffering above that of any other woman. As a result our sympathy for Griselda is diluted, which significantly weakens her dramatic impact. Nevertheless, Falaschi had Ann Hallenberg, cast as Griselda, embrace the role of victimhood for all it was worth, so that she appeared downtrodden, depressed, and lost. Apart from occasional flashes of defiance, there was no sense that she was a queen, possessed of royal bearing.

Hallenberg, however, made the most of the situation, with a well-sung performance, despite the orchestra being a little heavy on occasions. Her final aria “Son infelice tanto,” in particular, caught the attention and was beautifully rendered. Her delicate and emotionally sensitive phrasing perfectly capturing the depths of her misery as she yearns for death, and on this occasion was supported by an equally pleasing and sensitive performance from the orchestra. Her arietta “Sonno, se pur sei sonno,” although lasting barely a minute, was a real delight, allowing her to show off the grace, elegance, and beauty of her voice.

King Gualtiero was given a confident presentation by tenor Jorge Navarro Colorado. Although his actions are supposedly for the long-term benefit of Griselda, he did seem to enjoy humiliating her, which successfully opened up sadistic undercurrents within Gulatiero’s psychology, in what was a convincing presentation. His voice possesses a pleasing timbre that he is able to employ intelligently and with versatility, which he displayed from the outset with a successful rendition of his opening aria “Se ria procella sorge dall’onda.”

Two Standout Performances

There were two singers who certainly caught the eye with their bravura performances, both of whom received loud and sustained applause at the final curtain.

The first was the countertenor Kangmin Justin Kim in the role of Ottone, who not only pushes his unwanted attentions on Griselda, but also abducts her son and threatens to kill him if she does not succumb. There is certainly little to like about this character, and Kim ensured he was suitably disliked throughout the evening. Nevertheless, in what was a thoroughly engaging performance he wowed the audience with the stunning quality of his voice, which has a high tessitura, with a clean, clear and pure sound, but with such versatility he is able move with agility across the range, taking leaps in his stride and inflecting dynamic and emotional accents into the vocal line with ease, as well as injecting an array of colors into his singing. Of the three arias he has to sing “Dopo un’orrida procella” was certainly the most impressive, with its spectacular coloratura runs, leaps, and vocal movement, although the energy and technical surety which lay behind the delivery were equally notable.

The second singer of note was soprano Michela Antenucci, who was cast as Costanza. Having reviewed her on a number of occasions, a high quality performance was expected, and even though the role proved more demanding than those previously witnessed, she did not disappoint. Slightly reticent at the beginning she quickly grew into the role and produced a performance that positively sparkled, shifting seamlessly between periods of refined delicacy and elegance to passages of high energy and flamboyant spectacle. In the famous aria “Agitata di due venti” she showed off her clear articulation, her bright, versatile coloratura and dynamic flexibility to brilliant effect, while in “Ombra vane, ingiusti orrori,” an aria of a very different hue, she gave voice to her conflicted fears, in which she displayed her fine control in crafting thread-like phrases of the utmost beauty.

Countertenor Antonio Giovannini made a lackluster start in the role of Roberto. Everything was correct, but there was little fizz in his interpretation. His voice has a pleasing homogenous tone, but there appeared to be little effort to mold his singing to fit the needs of the text. However, during the second part he came alive. There was far more energy, his performance was far more spirited, his character took on a definite personality and his singing displayed far greater variety and emotional depth. For his aria “Che legge tiranna” he produced a passionate reading, full of dynamic and emotional inflections that brought out the full extent of the anguish and pain he was suffering at having his lover Costanza unjustly taken from him by Gualtiero.

Mezzo-soprano Rosa Bove is a La Fenice regular, and her appearance on this occasion as Corrado marked her third in a Vivaldi opera, for which she produced an energetic, lively and convincing performance. Although a fairly minor role, it contains one of the Vivaldi’s better known arias “La rondinella armante,” for which she produced a solid performance.

While there were certainly problems with both the staging and musical direction, the quality of the singing managed to prevent the production from being deemed a failure. In fact, La Fenice’s “La Griselda” is worth seeing for this reason alone.