Teatro La Fenice 2020-21 Review: Farnace

Christophe Gayral’s Presentation Fails To Convince

By Alan Neilson(Credit: Michele Crosera)

The director for Teatro La Fenice’s production of Vivaldi’s “Farnace,” Christophe Gayral observed in his program notes that “the music for some of the arias is strangely sometimes not completely related to the narrative, the music is light while the situation is dark.” While this is undoubtedly true, it does not act against the work as a whole and is fully in line with the conventions of Baroque theater. Certainly, the narrative is for the most part dark, not to say violent, yet it ends as is usual with operas of the period with a lieto fine, in which the good governance of the ruler restores order and harmony. It is fundamentally optimistic in outlook! Part of the role of the director in such cases is to bring the music and the text together in a way that is coherent and understandable to the audience. Certainly, this can be difficult to achieve with certain works and “Farnace” may well be a case in point.

Gayral’s Misguided Direction

Gayral, however, took a different course of action. He decided he would promote the drama by simply ignoring the parts of Vivaldi’s score which he felt did not match “the situation.” Whether this was a deliberate misunderstanding or an error of judgment matters little. The consequences were fundamental and wholly negative. From the opening bars to the final curtain the audience was subjected to the bleakest possible interpretation of the text, with no relief whatsoever, in which the opera unraveled to the extent that in the final scene, contrary to what is written in Antonio Maria Lucchini’s libretto, all those who had opposed “Farnace” are slaughtered. There was no happy ending here, no forgiveness, no restoration of order, just the triumph of violence. Gayral had, in effect, changed the text and ignored what Vivaldi’s music was communicating, in order to solve a dramatic problem. It did not convince and actually drew attention to the incongruity between the music and the text, something he had unsuccessfully set out to solve.

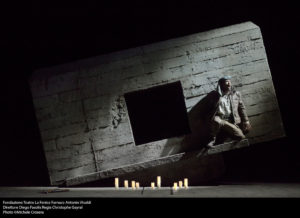

The drama was repositioned to the present day, somewhere in the Middle East, in which “Farnace” and his supporters were presented as a band of Islamist guerrillas, while Berenice and Pompey’s forces were of Western origin. The sets designed by Rudy Sabounghi were brutal in the extreme, consisting largely of burnt-out concrete buildings, for which the lighting of Giuseppe Di Iorio was used only to magnify the desolation and heavy atmosphere. Elena Cicorella’s costumes reflected the protagonists’ origins; aggressive, sharp, inhuman military uniforms for Pompeo’s troops and Islamic dress for “Farnace” and his fighters. The idea was good and individual scenes worked well, but their unchanging form weighed heavily, and along with the black backdrop made the drama feel one-paced, and at times bordered on the tedious.

Unfortunately, Gayral’s direction on an individual level was also largely unsuccessful. In his attempt to establish his characters he was, at times, too heavy-handed and appeared not to trust the audience. In his endeavor to highlight Berenice as a ruthless, heartless leader, we almost descended into farce; every time she sees her daughter Selinda, whom she holds captive, she marches over and gives her a good beating, then marches off at double speed because, after all, she is a woman with power and must be seen as such. Not once did she enter or leave the stage normally. And her evil looks, which she cast over her enemies, came straight out of a silent movie.

Gayral was equally determined to establish the brutality of the world in which the drama was set. The seduction scenes, for example, were presented so that the contempt which the women feel for their prey was obvious. Once again, it was too heavy-handed and suggested that the director did not trust his audience.

Fasolis’ Strong Musical Direction

Conductor Diego Fasolis has substantial experience in directing Vivaldi operas, with a fine recording of “Farnace” to his credit, and can be relied upon to deliver a quality performance. So it was with La Fenice’s production, in which he elicited energetic and precise playing from the Orchestra del Teatro La Fenice, capturing the somber emotions which run through the work, while also giving sufficient attention to the bright, lively pieces which underscore the optimistic nature of the narrative; although at times, the black, heavy staging made it difficult to fully appreciate it.

A Solid Cast

The cast as a whole produced a solid performance, but it was mezzo-soprano Lucia Cirillo, with her expressive and forceful vocal portrayal of Berenice, who stood out, in spite of Gayral’s heavy-handed directing. She captured the vicious, psychopathic nature of her character perfectly by spitting out her lines of recitative with venom and undisguised hatred. Her arias were excellent – displaying an impressive coloratura, well-crafted phrasing, and flexibility that allowed her to take leaps with ease. Moreover, and despite all her vicious ranting, she sang with considerable beauty. Her Act three aria “Quel candido fiore” in which she implores Pompeo to kill her grandson was chilling in its delivery.

Tenor Christoph Strehl was cast in the role of Farnace. He was somewhat inconsistent but delivered when it really mattered. Farnace’s aria “Gelido in ogni vena” in which he suffers from the belief that he had caused his own son to be killed, was sung with deep expressivity: imbuing his voice with an array of colors and degrees of emphases, his pain was palpable. Recitatives were, generally, very well-delivered, and showed off his neat phrasing and vocal flexibility. Moreover, with his robust physical appearance, he looked very much like a tribal warlord, which was spoilt by the ending in which he installed himself as a military dictator, dressed in a white over-the-top military uniform, with comedic overtones.

Sonia Prina has a very distinctive, strong, and flexible contralto. From the very beginning, it is clear exactly what you are going to get from her in a performance – fluid coloraturas which climb and descend with ease, and lines abounding with leaps and embellishments; in other words a veritable vocal pyrotechnic display. And in her role as Farnace’s wife Tamiri, she did not disappoint. The aria which caught the attention, however, was the more sedate “Forse, o caro, in questi accenti” in which Prina sensitively caressed the vocal line, and showed off the beauty of her voice

Mezzo-soprano Rosa Bove produced a strongly defined Selinda. Her singing was expressive, although not particularly expansive. Recitatives were presented with meaning and emotional strength. The aria “Ti vantasti mio Guerriero” was perhaps her strongest contribution, which was pleasingly delivered and showed off her coloratura and ability to control the voice to good effect. She too became a psychopath in the hands of Gayral who had her slitting Berenice’s throat in the finale.

Gilade, the captain of Berenice’s army, was sung by countertenor Kangmin Justin Kim. He has an attractive light voice with a beautiful, pure consistency, which he used to spin out delicate and graceful lines, and craft lively coloratura displays. The one drawback is that his voice does not project very well, which took some of the gloss of his performance.

Tenor David Ferri Durà played the role of the perfect Aquilio. He gave a solid singing performance, but the overall effect was lightweight, in which his emotions were too meekly presented.

Pompeo, who should have been dispensing forgiveness and justice during the final scene was unable to do so, as he too was butchered by Farnace’s men. The tenor Valentino Buzza, playing the role, gave a vocally strong, although not particularly subtle reading.

The Chorus, under the stewardship of Claudio Marino Moretti, was positioned in the boxes on either side of the stage and gave a strong, uplifting, and energetic performance.

Fundamentally Flawed

Despite certain positives on the musical side, this was a production that found it impossible to overcome the fundamental premise upon which the director based his presentation. His decision to basically ignore passages of Vivaldi’s music because they conflicted with “the situation” and then to ignore the actual text to allow his reading to have coherence was always going to be a tough one to sell. Gayral’s claim in his program notes that his interpretation was “faithful to the opera, but free at the same time,” did not prove to be the case: a free interpretation? Absolutely; a faithful interpretation? Absolutely not.