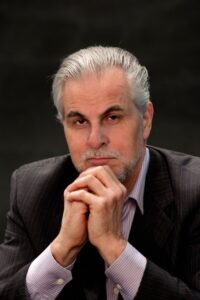

Q & A: Conductor Victor DeRenzi on 44 Years at Sarasota Opera

By David SalazarFor 44 years, Victor DeRenzi has maintained his position at the helm of Sarasota Opera as its Artistic Director. During that time he has led over 900 opera performances. Among his major accomplishments with the company is a Verdi cycle that he initiated in 1989 and completed in 2016 with the aim to perform all of Verdi’s music. He also started the Masterworks Revival Series to spotlight neglected operas and American Classics Series, which champions 20th century operas by American composers. Moreover, under his watch, the company has engaged in educational and outreach activities and founded the Apprentice and Studio Artists Program.

As he enters his 45th season, he will be the longest standing artistic director in the US. What keeps someone in the same position for so long? OperaWire spoke with DeRenzi about his time at the helm, his motivation, the change he’s seen, and what he still seeks to accomplish.

OperaWire: You have held this position for 44 years (longer than anyone in the history of opera in America). What are some of the biggest changes that the opera industry has undergone, in your view?

Victor DeRenzi: After 56 years of conducting, it is hard to separate the realities of that long ago time from the imagined past, but some things do strike me as having changed over the years.

When I first became involved in opera, my contemporaries and I found opera and the life on stage more interesting than our own lives. We wanted to enter that world, not bring our daily life to it. Going to a different time, a different place was meaningful. We were not interested in the personal lives of the people we admired or want them to know ours. We wanted to be part of what made the world of opera different.

I have known and still know and work with many talented singers, but what they’ve learned rarely comes from what they are taught at universities or conservatories. The training of professionals has changed. From what I have seen in auditions and what I know of the recent generation of music school graduates, people have come out of colleges with not enough of the skills they need to compete in the professional opera world. Schools accept too many students who don’t have a chance at a career, so they don’t have the time to teach those who might have potential. With schools fearful of being perceived as “difficult,” students are not held to a standard and are graduated when they haven’t gained enough of the information they need to have a career. Very often it is these people who then become college teachers. Everyone is encouraged to stay in school too long and watch as the possibility of a career passes them. I’ve always seen school like a hospital. The point is to get out.

Among the problems, the biggest has been in the teaching of vocal technique, which is the most important part of our art. Vocal studies have become about making sounds rather than communicating text. There is an overlay of so-called technique that has nothing to do with the history of singing or how singing had been taught over the years. I don’t think singers have less talent than those of the past; I feel they are let down in their training.

The “opera industry” has become too interested in things that have nothing to do with opera. Organizations like Opera America have tried to influence companies to fulfill its own particular agenda rather than that of the individual communities where companies are located. There is too much fostering of non-musical issues that a service organization should not be involved in. Those of us who run opera companies and love opera should trust our feelings and our talents rather than look for a generic approach to opera that doesn’t work for every community. What works in Detroit might not work in New Mexico or Florida. Even though a study put out by Opera America said that new opera goers want to see standard opera in traditional productions, the opera industry is encouraged to do anything but that. Looking at recent repertoire choices by opera companies: I see confusion about how to sell tickets seemingly caused by trying to stick to an imposed agenda rather than a belief in opera and building an opera audience.

OW: How did the changes impact the directions you took with the company?

VDR: The changes have impacted my company and others as well in that we have had to take on the training of singers and pianists to make up for what is not taught during their music education. The idea behind apprentice programs was originally to bridge the gap between school and professional life. That gap has become bigger, so companies have had to fill it. After years of school, singers should not have to depend on an apprentice program or a “pay to sing” program to get the information they should have gotten in college. How about an MD graduate who has to pay to practice medicine? Pianists who study “collaborative piano” spend too much time on music they can never make a living performing, and they are not encouraged to learn the repertoire which can give them a future in opera companies. Much great music is found in art songs, but learning the most performed arias and operas is more useful.

Another change has been in how elementary and high schools teach music with a focus on contemporary pop music rather than the important works. Arts organizations have to do what schools used to do by introducing our art form to students. I don’t see why the arts budgets are constantly cut while sports seem to remain abundantly funded.

The most challenging aspect of having an opera company has become casting operas that require bigger voices and big emotions. There is a constant message given to singers about being “too young” to perform the dramatic repertoire. A few years back, singers starting out were not told this. The standard arias were Verdi and Puccini, and you were not encouraged to be a lyric singer until you were 40 years old. Singers are constantly given reasons to delay their vocal growth that have nothing to do with reality. Opera houses are not bigger — orchestras may play louder but they are not bigger — and a voice does not need more time to mature today than it did 50 years ago.

OW: What are the greatest challenges you overcame in that time?

VDR: My greatest challenge has been to stay firm to what I believe opera should be, even though it may not have been, nor is, the status quo of opera performances. I do what I believe in and not what everyone else does. Doing new repertoire is important, but that doesn’t mean everyone has to do it and it certainly can’t be at the expense of building an audience. We talk about doing new works as if this is a recent idea in opera. There has always been a place for new repertoire in opera in America — the original New York City Opera and Houston Grand Opera come to my mind first — but the musicians running companies understood that works had to be musically viable, not just dramatically interesting and that you had to program them in a way that did not alienate your audience.

I have not changed my belief that the power of opera and the emotion of singing can affect an audience. I have always hired people that I like or might like and people whose talents I believed in. It was never important to me what other people thought of certain singers, what companies conductors had worked with, or what was on someone’s resume. If their performance spoke to me or if I saw a possibility for that, I wanted to work with that person.

OW: How have you changed as an artistic director in that time and what have you learned?

VDR: My approach to music has changed drastically. I grew up at the time when people were trying to do exactly what is written in the score. I came to realize that what is called Performance Practice applies to romantic/operatic music as much as it does to baroque music, and that one must consider not only what is on the page, but the times in which composers and librettists worked, how they worked, and the aesthetics of the country where their music was created. That has led me to find more freedom in the music than when I started conducting.

OW: Remaining at the helm of an opera company for a long tenure is very rare. What has motivated you to remain with Sarasota Opera for so long?

VDR: When I first came to Sarasota Opera, even though the company was very small, doing a limited number of performances with very reduced forces, I felt there was potential for growth. I had wanted to develop a company that could reflect my feelings about opera and how to prepare it. I had wanted a festival situation where people would come together as a community and perform opera, without the distractions of everyday life. The standard for that was — and still is — summer festivals. But why not one in the winter? Sarasota was a place to do that. I was more interested in building a company than going from theater to theater to conduct.

OW: How has your connection to the community developed over the years and how has that influenced your direction with the company?

VDR: The city of Sarasota that exists today is nothing like Sarasota when I first came here in 1982. Most of that is due to Sarasota Opera and the other arts organizations. The Opera House is celebrating its centennial this coming year. When we bought the building and renovated it, the downtown area of Sarasota was barely functioning. Now it has grown with housing and restaurants that would not have been possible without the cultural center that is found in our opera house. The Opera House is a vital part of the city.

OW: For people unfamiliar with Sarasota Opera, what are, in your view, its defining attributes? What makes it so special and why do you think it’s essential for people to experience it?

VDR: I try to do performances that are impassioned and based on communicating the text and the story that was given to us by the works’ creators. We do productions that respect the composer’s and librettist’s wishes. That doesn’t mean that we expect singers to just walk to the footlights and sing. Every performance is thought out and has a specific artistic goal. We try to make everyone part of the emotion of the work: the orchestra, chorus, staff, etc. Several years back when we did “The Crucible” and “Of Mice and Men,” both the composers, Robert Ward and Carlisle Floyd, came to see our productions. They said what they saw in Sarasota was better than many productions in recent years and were very glad we followed their dramatic wishes as well as musical intention. Often people make assumptions about seeing traditional productions without having seen one. I don’t know of a production of, say, “La Bohème” that follows Puccini’s stage directions as much as we do and tries to bring them to life.

OW: Tell me about the 2025-26 season and how you arrived at this programming for your special season? What are you excited for audiences to experience most in 2025?

VDR: Every season is special for me. They all have what has become part of our image over the years: doing a combination of works that are constantly performed as well as [some] less familiar. Our audience has the opportunity to see all our operas in a very short time, so doing “The Merry Widow” will be a contrast to “Susannah” by Carlisle Floyd, a strong piece dramatically and one that can be very disturbing. With “La Bohème” and “Il Trovatore” we continue our commitment to the great repertoire that has kept opera alive for centuries and still continues to bring us new audience.

OW: How did you originally come to the world of opera? At what point did you know that you wanted to be engaged with this artform long term and what motivated you to pursue this path?

VDR: When I was in elementary school, I had a teacher who built sets for a small opera company on Staten Island NY, where I grew up. He kept encouraging a group of us to go see a performance and, in an attempt to make him stop bothering us, a few of us went. It was “La forza del destino.” We thought we could be polite and tell him how much we enjoyed it, but that we wouldn’t need to go see an opera again. At least that’s what happened with everybody else. That performance with a piano, not very good singers, makeshift sets, and no chorus showed me something I had no idea existed. I started helping my teacher build sets, I was a super in productions, and I eventually started singing in the chorus. At that time, I really liked opera, but when I bought a recording of “Aida” and heard Renata Tebaldi sing, I became obsessed with [it] and with a love of singing. I had already been studying music, but I have always had what I think is an unpleasant voice. As a teenager I really admired the man who conducted that small company and I wanted to do what he did. Starting at that time, all of my interest was in classical music and opera, at first just seeing it, but eventually being a part of it and performing it. Like many of my contemporaries, I became steeped in it.

OW: Looking forward, what are some new things that you hope to accomplish with the company?

VDR: As I mentioned, this is the 100th anniversary of our Opera House, which will be celebrated in a two-day event involving much of the Sarasota community. We are planning continued collaboration with other Sarasota arts organizations. We are looking forward to producing neglected works that are worthy of performance. There are many works that either have not been done recently or are not done as much as they used to be: lesser-performed Verdi operas, as well as works not seen in America beyond big cities, like “Fedora” or Zandonai’s “Francesca da Rimini.” Since our mission is to perform opera as the composer intended and not scaled down, those works can be appreciated in our 1100-seat theater in a way that is not possible in some bigger theaters. In the long run, opera will be fine if we trust it and remember it will be here long after we are gone.