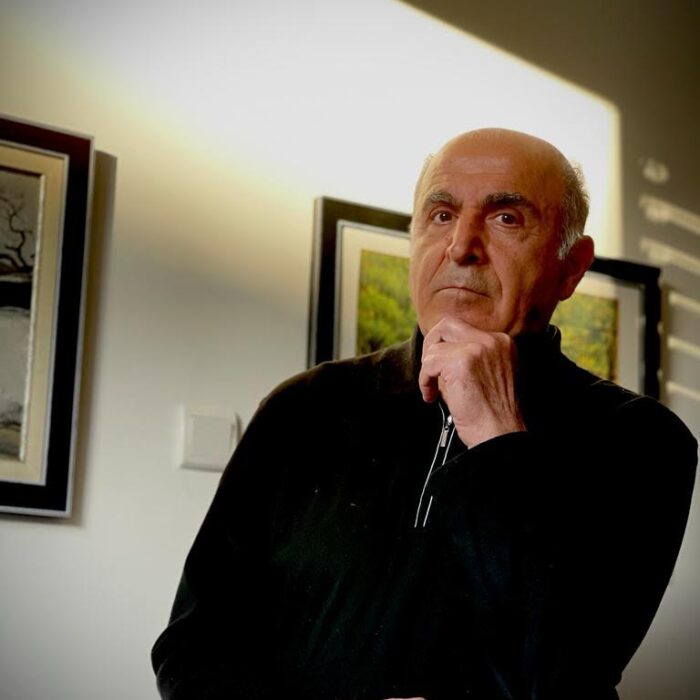

Q & A: Composer Yair Klartag on His Azrieli-Winning Commission ‘The Parable of the Palace’

By David Salazar(Photo by Anne-Laure Lechat)

“I was lucky to have a great music teacher in my teens, who gave us very inspiring compositional assignments. I remember the experience of going to school as a teenager and thinking about my compositions I was writing for the class, and fell in love with the experience of spending my thinking time on abstract sounds. There was something about how elusive sounds are, and at the same time so visceral, that was a very good fit for how my natural thinking and creativity functions,” says composer Yair Klartag in an interview regarding his Azrieli-Winning commission “The Parable of the Palace.”

The Israeli composer has been commissioned by such organizations as Donaueschinger Musiktage, Münchener Kammerorchester, MATA festival, Münchener Biennale, and ZeitRüume Festival, and his music has been interpreted by such ensembles as Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, Munich Chamber Orchestra, Geneva Chamber Orchestra, Tokyo Sinfonietta, Wrocław Philharmonic Orchestra, Ensemble Recherche, Ensemble Musikfabrik, Ensemble Mosaik, Ensemble Linea, Meitar Ensemble, and the JACK quartet, among many others.

OperaWire: What inspired “The Parable of the Palace?”

Yair Klartag: It is named after a parable that appears in the end of the “Guide for the Perplexed” – an amazing book by Maimonides (1138–1204), in which he tried to reconcile Aristotelian logic and reason with the Jewish beliefs. It tells the story of a palace, in which a mysterious king lives. There are different groups of people in different circles around the palace in different proximity to the king. The piece takes from the parable its geometric organization: in the core, there is the irrational – what goes beyond reason – and around it different circles with varying distances from the irrational. The inner circles are the circles of logic and science (that’s how Maimonides himself interprets parts of this parable). This image of circles surrounding an irrational core inspired the structure of the piece – the music spirals and circles around a very abstract musical material built from low double basses sounds and vocal material from the choir. The text is sung in its original version in Jewish Arabic. This is an extinct language that was used in Jewish communities in Arabic countries during the Middle Ages (Maimonides was residing in Egypt while writing his book) – it uses mostly Arabic words but written using the Hebrew alphabet. It was an important point for me to discuss such universal ideas (reason and irrationality) through the writings of a Jewish thinker who learned about Greek philosophy through Arabic translations. In the face of the horrors of the present, it was helpful to connect to a common humanistic historical universalism like that.

OW: Describe the musical language of your piece and how you arrived at it.

YK: The piece is always moving in space – between high, dreamy sounds to low and earthy fundamentals. The general atmosphere is very mysterious with many slow morphing sound glaciers and some ancient-sounding melodies emerging. It’s a musical language that tries to hint at the medieval nature of the text and the perceptual space that is between the rational and the irrational.

OW: What inspires your creative process?

YK: I can name three main sources of inspiration: the content of the text (meaning the parable) and my understanding of it in terms of Maimonides’s position towards rationalism and beliefs, the language of the text – the jewish arabic – with all the cultural heritage and complexity it carries, and the instrumentation – the massive four double basses with the huge spectra and their interaction with the choir.

OW: What were some challenges you experienced while creating this work?

YK: It is always a challenge for me to deal with concrete text, and in this case, with text of jewish origin. For many years I wanted my music to be completely universal. In recent years, I discovered that the type of universality I was looking for, relates in many aspects to some parts of the Jewish heritage that I wasn’t fully aware of. I was enchanted with diasporic ideas of replacing territory with books and writings as a way of existence and longevity. I found the unbelievably rich corpus of ideas, especially around the metaphysical and the way Middle Ages thinkers like Maimonides or Saadia Gaon understood rationality was extremely relevant to my upbringing. I still don’t know how to define jewish music, but one aspect that I notice is recurring among jewish writers is “doubt” – there is at the same time adaptation of artistic romantic ideas, and a constant disbelief in their authenticity. This is very noticeable in writings of people like Heine and Kafka, and I have noticed that it is very relevant to my music as well.

OW: What do you hope audiences take away from the experience of your piece?

YK: I hope people can immerse themselves in the dreamy atmosphere of the piece, but still be conscious of what are the processes that happen and where the music is going. I hope it raises some question about how our rationality works and what’s its role when experiencing music and maybe blur the limits between the reason and the pure experience.