Q & A: Composer Paul Mealor & Librettist Grahame Davies On Their New Opera ’Gelert’

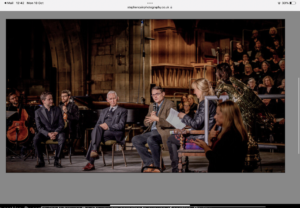

By Alan Neilson(Stephen Cain Photography)

The North Wales International Music Festival this year celebrated its 50th anniversary, and to mark the occasion, commissioned a new opera from composer Paul Mealor and librettist Grahame Davies.

Together they decided to base their opera on the tale of King Llewelyn’s faithful hound, Gelert, a legend known to even the youngest of Welsh schoolchildren. The subject was deliberately chosen so as to appeal to the whole community, and in fact, the opera was labeled as a community opera.

The premiere took place in the cathedral of the small Welsh city of St. Asaph. Two versions of the work were performed, one in Welsh, which took place in the afternoon, and one in English, which took place in the evening. Again, this was a decision taken so that it could appeal to the whole community. The performances, containing both a children’s and an adult choir, three soloists and a small orchestra, were warmly received by the audience, who joined with the cast at the end in a reprise of the final chorus.

However, apart from appealing to the community, which is certainly a noble aim in itself, what exactly do Mealor and Davies mean by a community opera? In between the performances, OperaWire sat down with the two creators to talk about the opera and find out.

OperaWire: What are your creative backgrounds?

Paul Mealor: I grew up in Connah’s Quay, but I was actually born here in St. Asaph and was a choirboy in the cathedral. I started studying music with William Matthias, the festival’s founder, which was a bit daunting as I was only nine at the time. I then went on to study with Nicola LeFanu and then Hans Abrahamsen. I decided at an early stage that I didn’t want to be pigeon-holed and that I wanted to be able to write music of all types. So this is what I do: I write everything from TV and film scores to symphonies and concerti to pop-songs. I love being able to do this. My inspiration comes from people like Malcolm Arnold and Richard Rodney Bennett, who could turn their hands to everything. I am also a Professor of Music at the University of Aberdeen, but I am doing less and less of this now, but I was full-time for 15 years.

Grahame Davies: I am from Wales, and I started out as a Welsh language poet. In the late 90s and early 2000s, I started to work in English. Since then, I have worked bi-lingually, writing volumes of poetry in Welsh and English, which initially centered on social commentary. Then I moved on to novels and social history. Since 2003, I have been working on libretti for classical composers. I started collaborating with Paul in 2013.

OW: How did you get in touch with each other?

PM: It was through a commission from Salvi, the harp company. They built the harp for the Prince of Wales. It was his 65th birthday, and they wanted to do something for him, so they brought us together and commissioned “A Welsh Prayer” for choir and two harps. It was performed here in St Asaph’s cathedral with that harp in 2013.

OW: What sort of working relationship do you have?

GD: We get on very well. Sometimes Paul receives a commission and calls me, and sometimes it goes the other way. We rarely have disagreements. For this opera, I wrote a section early on in the opera which was a historical preamble conceived in a mock heroic, playful style, and Paul said it just doesn’t fit. That’s completely fine. I would rather write too much and trim it down. Things end up on the cutting room floor, like in many creative activities, such as film-making.

OW: What do you mean by a community opera? How will it differ from a normal production?

PM: My first thought was to create a community event to mark the festival’s 50th anniversary, but what should it be called? Is it an opera, a musical, or something else? How would I define it? This is difficult. How do you define an opera? How is it different from a musical? It is to do with style, with syntax, with voices, and how you deal with the narrative, in much the same way as Benjamin Britten did with “The Little Sweep.” I landed on the idea of a community opera, as it is a work intended to involve the whole community. It is a community event, for want of a better term.

We wanted to include everyone we could from the community, and of course, when you do that, there are a variety of standards in the performances. Some people can produce a fabulous performance, and others less so, in terms of how you would classically define good and bad. So it is necessary to write music that can include everybody, and that is very difficult to do.

The idea is to move the opera around so it can be played in church halls and community centers. Most communities are likely to have groups of musicians, such as a pianist and someone who can play the violin, and I have to write music they will be able to play. The music can’t be too difficult. Yes, there will be difficult parts, but I have to be practical about this.

OW: What drew you to the legend of Gelert?

PM: There are plenty of Welsh legends, but we wanted a story from this part of the world. Every single child involved in this knows the story. It is about friendship, it is about loss, it is about big issues.

GD: And we also thought about the relationship children have with animals. We give children animal toys when they are babies, they watch animal cartoons, and they have animals as pets. They have a special relationship with animals; they are a sort of transitional object, that can stay with us throughout our lives. They appear to be crucial to children’s emotional development. The legend of Gelert has this relationship at its heart, as well as that of loss, an unjust loss, and in the original story, it is an irredeemable loss. There is no happy ending in this story, and that is the challenge we have to deal with, and what appealed to us about this story.

There are many children taking part in this opera, and they will be able to relate to the emotions of the story.

OW: You have changed the story slightly. Llewelyn recounts the events in old age, and the role of the wolf is expanded. What was the thinking behind this?

PM: Very few species kill like we do. If you look at wolves, they are very social animals and kill to stay alive, but we tend to anthropomorphize them. We never hear from the wolf, and it was Grahame’s idea to give the wolf a voice. I mean, was the wolf actually going to attack the child? We don’t know.

GD: Of course, behind this is the idea of the shadow, the denied parts of our psychology from Jungian psychology. So we gave Llewelyn the opportunity to admit the wolf rather than exclude it and treat it as an external threat. I thought it would be interesting to use that element and integrate it into the work at the end. This is quite challenging material; we dealt with the unjust, premature loss of a beloved object, but then there is also the challenge of what to exclude and why we are excluding it, and are being honest in so doing. We are trying to speak about the question of “othering.” It seems to me, these days, everything is being polarized, and everyone wants to be pure by condemning someone else as completely reprehensible, which clearly can’t be right. This is an attempt to see the light in the darkness and the darkness in the light, and to integrate these polarized positions. The wolf and the hound are two expressions of Llewelyn: the part he wanted to admit and the part he wanted to exclude. In the libretto, I have Llewelyn admit Gelert when he turns up at the door. So, in this context, Gelert is a proxy or a symbol for Llewelyn’s faithfulness and goodness, an expression of what Llewelyn wanted to believe about himself, and the wolf was an expression of what he refused to admit about himself, and so is excluded. Then there is the question of Gelert being rescued, and to what extent this is compassion and to what extent it is narcissism.

OW: How long did it take from the initial idea to completion?

PM: The initial idea was quite a while back.

GD: Yes, but the writing didn’t take too long.

PM: I would say about two years in total.

GD: Yes, but it was complicated by the fact that the libretto was originally written two-thirds in English and one third in Welsh, but then the festival asked for two libretti, one in English and one in Welsh, so I had to write out the other parts, but obviously they couldn’t be literal translations. I had to get the rhyme correct.

OW: So there are two versions of the opera, one in Welsh, and one in English. The two languages are very different with regard to cadences, intonation and rhythm. How did you go about creating the two versions? Are they different in any way?

GD: OriginalIy I wrote the text, which Paul then set to music. Then when they wanted a completely Welsh version and a completely English version, I had to translate the parts and mould them to fit the music, which can be quite tricky, but we have worked on bi-lingual compositions before. So, although the texts are not identical, the stress patterns are the same, and the overall meaning doesn’t change. It is actually easier to translate your own work than someone else’s, as you know exactly what your own intentions are, and what you want to say, and how you want to say it.

PM: I didn’t have to do anything. The two versions are musically the same.

OW: How did you decide on the format of the text?

GD: The intention was to provide a variety of formats for the composer to work with; a variety of line lengths and a mixture of rhyme and prose to accommodate recitative, duets and choral pieces. It is mostly in rhyme because it helps with accessibility, which is important for a community opera.

PM: One of the biggest criticisms of opera is that it is all recitative, and we didn’t want that. From the beginning, we decided to create something with duets, arias and trios. Obviously, there has to be some recitative to move the opera forward, but we kept it to a minimum.

OW: What type of musical language did you employ?

PM: It is tonal, but there are sharp edges to it. I had no option really, because when you are writing for a community choir you can’t write something like Ligeti as they wouldn’t be able to sing it. So it has to be kept fairly simple. It has parts which are tricky parts. For example, at times the choir has to sing unaccompanied, which can be difficult, but it is possible. It can be learnt. There had to be melodies, particularly for the children. I could push the orchestra more than the choir, so the writing was more demanding. I wanted percussion in there to create a disconcerting feel that runs through the piece.

I modeled the work on the music of Benjamin Britten, Malcolm Arnold and Richard Rodney Bennett.

OW: How did you decide on the orchestration?

PM: it was written for piano, flute, violin, cello, clarinet and percussion. The idea behind it was that it is the kind of group that you could find in most towns and places, but I also wrote alternatives in the score, so that if you don’t have a clarinet or a flute, there are transpositions available.

I wanted lots of colors and textures, and the percussion adds a lot of color. Generally, the piano is a kind of body. It provides the notes and harmonies, and the other instruments are there to add color to the duets and other parts, and are also used to bring out the line a bit more. I also used the orchestra to fill out the drama and to create a bit of an atmosphere in the quieter passages.

OW: What did you expect from the singers?

PM: I know the singers. They are professionals, and I know what they can do. So I wanted to give them a bit of variety, and I wrote to their strengths. I think they did a good job.

OW: How pleased are with you with the performance?

GD: It turned out much like I expected. I thought it was great.

PM: Yes, it was very good.

OW: Do you prefer the English or the Welsh version?

GD: Well, as it was originally written two-thirds in English, I feel that it has primacy, so I would say my preference is 66% to 67% in favor of the English version.

PM: One of the funny things about today’s performance is that the majority of the choir speak Welsh as their first language, and, therefore, they found the English more difficult to sing. So the evening’s performance will be more difficult for them.

OW: How would you judge the success of the opera? Would you consider it a failure, if it were not reprised?

PM: If it wasn’t performed again, I would be disappointed. But I don’t judge success or failure by popularity. I remember William Matthias, the festival’s founder, once said, “Pieces survive because people want to perform them, not necessarily because people want to listen to them.” The buzz from the performers and the audience today makes me think we achieved something. As long as we have done what we set out to do, and as long as the performers and audience got something out of it, then we have succeeded. The intention, however, is to tour it around Wales next year.