Q & A: Alexander Shelley & Joel Ivany on What Makes Opera a Vital Part of Canada’s Vibrant Culture

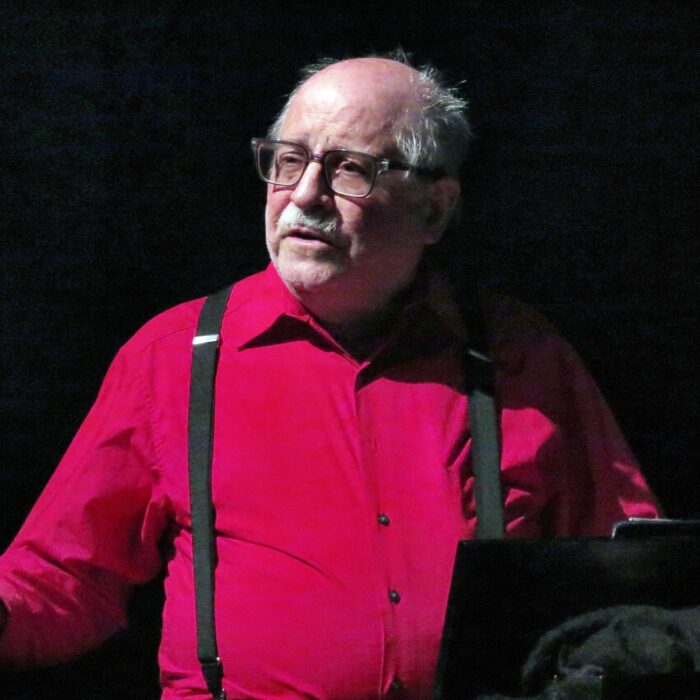

By Jennifer Pyron(Photo: Alexander Shelley © Rémi Thériault / Joel Ivany © Taylor Long)

OperaWire recently attended Canada’s National Arts Centre (NAC) for their National Arts Centre Orchestra (NACO) semi-staged production of Puccini’s “Tosca.”

The day after their opening night performance, OperaWire was invited to sit down with the Music Director and Conductor of NACO, Alexander Shelley, and the Artistic Director of Edmonton Opera, Joel Ivany, and learn more about what makes opera a vital part of Canada’s vibrant culture and how including more opera in the repertoire of orchestras promotes positive change.

OperaWire: Alex, what brought you to the NAC in 2015 and inspired you to take on the roles of Music Director and Conductor?

Alexander Shelley: The short answer is: I fell in love with the orchestra. I came here years before that in 2009 for my debut with the orchestra and I started to come every season and as I’m sure you know, it’s a weird thing how and why chemistry builds between certain conductors and orchestras. Sometimes it does, and sometimes it doesn’t. In this case, it did and I remember not knowing that much about the organization or the orchestra and having my socks blown off, thinking: oh my god this is a fantastic group of musicians. So, I loved coming back. I came back in 2012 as one of my visits and debuted “La Bohème” with Opera Lyra which is now defunct. During this time, I learned a bit more about the history of opera in this city, including the great summer festivals, amazing directors, and productions that came through and the amazing work that this orchestra and singers did. I loved doing “Bohème” and spent a bit of time in the city during that production and really understood the quality of life in this place. Ottawa is a G7 capital with all the trappings of interesting diplomats and politicians in that hub. You get anywhere in ten minutes. You can be in the hills in 15 minutes for skiing and hiking. And the artistic relationship with the orchestra continued to blossom and grow. They had a long tenure with Music Director Pinchas Zukerman, a legendary violinist who was my predecessor, and they took their time looking. I was approached about the opportunity while in Nuremberg at the time said absolutely I would love to be considered for the role. I began as a Music Director designate and then took over in 2015. This is my final season, 2025, and “Tosca” is the opening project. I have mixed emotions because right now I’m in the thick of the artistic and I’m not really thinking about the end of my tenure. That’ll come in eight months time, I think. But in the meantime, I had two children born here. They’re Canadian and just born a couple of miles away from here in the hospital. I’ve had an unending number of extraordinary artistic experiences with this orchestra. I remain their biggest fan. They have an extraordinary collection of musicians and people, and my mixed emotions are because this is the kind of place you never want to leave. But I believe I’m leaving at a place where the orchestra is on an upward trajectory and the momentum of the orchestra is upwards. It’s been a wonderful time and continues to be.

OW: How would you describe your learning process while in this role and over the course of 10 years?

AS: I would say that everybody is always learning everyday. Particularly with this organization what has been so fascinating is the Federal Mandate as well as the local. I’ve found the combination of conversations between reaching and speaking to local audiences, growing local audiences, but then thinking about the responsibility to also be a stage for Canadian artists from across the country to lean into commissioning works and doing the things that many organizations that are funded differently from us. We have direct federal funding, in thanks to the politicians that make the decisions being pretty stable and the work that goes into that. I’ve loved being part of the conversation around why one would have national arts organizations and what the responsibilities are of those organizations. For me, as an artistic leader, what work I need to put in, in order to support the ecosystem. This is, I think, a very beautiful and rewarding privilege and I’ve learned a lot through it. It’s something I’m, in a sense, addicted to. It’s actually quite rare there are not many orchestras in the world that serve as a national mandate in this way and that’s something I’d very much hope to have in my future as well.

OW: Is there a recipe that you designed along the way that made you feel capable of balancing all of these expectations in a free-flowing way?

AS: We’ve commissioned, up until now, 50 orchestral works since I’ve been here over the course of ten years, which is actually quite a lot and we are continuing to do it. Right now, for example, we have what I also need to balance for the orchestra, for example, our audience. You know we all experience life in two different ways. We all need to have the meal that we know we love and we know how to cook it with the same ingredients. I need that–which is why McDonald’s works. (You know whether you’re in Timbuktu or in London, you get the same thing. Whether you like it or not, you get the same thing.) And then you have to balance that with the new and the exploration. I think the local and healthy ecosystem of an audience is a concert hall where you both cherish the museum pieces and see them brought to life in different ways but particularly because there’s a rhythm in engaging with the creation of our time because then you are reminded that Puccini’s creation, Beethoven’s creation were born out of an era where they were very violent and they were discussed and they were poked and prodded. They remind one self that those were living beings that weren’t museum pieces when they were created. And this is so obvious–I find the juxtaposition between the old and the new are very important. We’ve started to get into a real rhythm of that with Strauss tone poems, a recording cycle of them, to sort of push and elevate the orchestra’s relationship to them artistically. We’ve also commissioned, for each one of the tone poems, a partner work–a response work from our time from great Canadian composers of all different stripes. By the way, that’s another great thing about the age we live in and terrifying if you’re a composer–every musical language is being explored. Every single one. So, Puccini had somewhere to begin with a mid to late romantic language. For composers now, one can go back to Monteverdi’s language or be completely open and free and use electronics. Where do you start? I imagine this would be a bit daunting for them, but there are some brilliant voices. It’s a combination of old and new, and trying to make, through that combination, everything feel vibrant.

OW: I want to segue from this same thought process and ask Joel: how do you feel your creative process keeps you abreast of the old and the new, while being a contemporary Artistic Director?

Joel Ivany: It’s like cut and paste in terms of everything is old and new because you need to know where you started from and what gets people’s attention, what they know, but then where do you go with that and how do you either make something old brand new. In terms of, it felt like last night (NACO’s “Tosca”) there were people watching this opera for the very first time and they didn’t know how to respond and so that is kind of a beautiful thing because you’re free to imagine what architecture can look like and hint to it with lighting, but then ask: what does the church look like? I played with taking old music and putting new text on it. When “Tosca” premiered, the opera used to be in Italian in Italy and English when it was in London. When it went to Germany it was in German, so I played with this and the different responses the audience had when hearing opera in their own language is very different; they laugh when they hear it as opposed to when they read the surtitles above. So, it’s that relationship which is beautiful to hear: how you’ve tied to build that relationship with the audience and see how that trust develops where they may not love everything you do, but they trust you enough that they look forward to the next one and they can’t wait for the next one as well.

OW: I think it’s interesting how you mentioned “Tosca” felt brand new because that’s one of my takeaways from last night’s production. I’m curious about how working with the singers really allowed you to have that response with them– to make this feel brand new– when most of them come from a traditional and classical staging of this opera. I am interested in knowing what you both have to say about working with the singers directly and what you learned along the way.

AS: A semi-staged opera like this is an animal of its own because having the orchestra on stage and hearing facets of the score and the resonance differently, the balances naturally can be different. But there’s also an opportunity for us to just go back to the score again, to remind ourselves where certain rallentandos are printed and we can work with them from where the singer’s dialogue arrives. Ailyn Pérez, who knows the role of Tosca backwards and forwards, having performed it all over, performing it here with Matthew Cairns for his first time–what was so beautiful was to see the meeting of those two kinds of preparation. One has to work from muscle memory that has been prepared for years and rework some areas based on looking at the score together and the rallentandos. Matthew came in as super prepared and took his role debut very seriously. We had fun with this and there were a lot of little details that we just tried to re-explore.

I do this in a lot of symphonic work and know that the person who knows the piece best is the person who wrote it and if they suggest this metronome mark, for example, then the first thing to do is just try that out. I have never had an experience where this doesn’t work. There are reasons, totally valid reasons to do other things, and some traditions have evolved totally but it’s always fun to go back to the original score. This is what we did for “Tosca.”

Then you also have the extraordinary part of the opera which is the live singing of the singers, which is a human feat. The language, the movement, the vocal performance, the acting. It’s all part of the fun of a live performance and we were trying to tighten up the timing together.

JI: You even said, at that moment, “more urgent,” and I think that from a story and director’s point, Mario’s friend, a colleague who he knows, (Angelotti) is hiding out, maybe even dying in the chapel. So, it’s like, I want to check on him, and I think that’s in the drama and is written as well, which it’s easy to forget that because there is the beautiful love duet (‘Ah! quegli occhi’), and it’s so beautiful you want to just enjoy it. But there is a big difference between this and what Angelotti is experiencing at that moment.

AS: I find at the beginning of that scene, they don’t present as totally balanced individuals. She is pissed as hell and obviously a jealous person, and Mario is living this totally bohemian lifestyle. So we are meeting two typically flawed artists living like this and so it makes it slightly unstable between all the beauty of Puccini’s score and I felt it would be nice to have markings that make sense of that.

JI: We looked at the score’s details with the singers and went by what it said, based on where the cast was at certain points, and tried this out together. It’s great to work with singers, who have performed this role many times and who are still open, along with singers who are making their role debut and looking at this for their first time. This makes the score come alive in a new way.

OW: I felt like there was a multidimensional experience unfolding on stage among the singers and the musicians. The use of the stage as a whole, when there was action taking place or a sense of urgency, really made Puccini’s throughline feel very fluid and this opera flew by. And, this is Puccini, but it is also the magical recipe you two made together that felt like a cinematic experience.

JI: You do your job in order to make it look very seamless, and a lot of the rehearsals are just timing of the little stuff that happens around there. I worked one time with a conductor on a Verdi opera in the United States where we needed two more bars to change the set and he decided to just play two bars, two more times and it was very freeing to not be bound by strictness. I felt like last night (“Tosca”) was seamless in these little corners.

AS: I find opera particularly interesting when it comes from those sort of discussions around where one can take it because on the one hand, for what it is, “Tosca” is perfect. It flies by because Puccini has paced it so perfectly. But then with Mozart, for example, we know that when he wrote a scene, he would have a different singer try it out and then if that would not work at all, he would just completely rewrite it. So there was nothing inevitable about the opera because he was the arch pragmatist. He just happened to, when he did change something, also be a genius at doing it. There’s also the linguistic element. I’ve longed felt, particularly for contemporary audiences, the immediacy of hearing an opera in one’s own language is unbelievably valuable. And yet of course there are aesthetic changes to the sound of the music once you take it out of Italian and put it into German or another language. But, I know that, well what is your take on that?

OW: I don’t really have a position on that because I love understanding opera through multiple perspectives. Opera as a whole, for me, is a play-out of the human experience through the story and the language, especially when I hear opera in English, is remarkable, but when I hear opera in Italian it becomes very dreamy.

AS: Yes, and sometimes it’s disappointing because you discover they’re talking about a breadbasket (everyone laughs).

OW: But it sounds most beautiful in Italian!

(everyone laughs)

OW: Nathan Berg as Scarpia in last night’s performance felt like he was really part of making “Tosca” feel brand new, too. I feel that in full staged productions his role is the villain who is often in the background doing the dirty work, but it was really cool in this semi-staged production to see him at his desk at the front of the stage with his laptop propped up for all to see. I want to know what your process was like when working with Berg to develop his character.

JI: Part of the aesthetic is when you walk into this beautiful space and see the orchestra on stage wearing beautiful clothes, in some instances if the performers were wearing traditional costuming maybe it would transport the audience somewhere? But what we get with this production is when we see the projection screen at the back, and the television on stage right, along with the digital camera as the props, it’s not necessarily foreign to what is today. And this is the thing, it’s June 1800s but we are in 2025 and somehow it just works really well. The corruption and abuse of power is something, again, you just go on your phone for five seconds and see it everywhere and it feels relevant in this way.

AS: What I find is that the actual story of “Tosca” can be set at any time. It’s an opera where Napoleon just won the battle. But, to me, the framing of the music and the politics is to underscore certain aspects of personality which is that whatever the belief system is, Scarpia excuses his behavior which is very human. That jealousy and violence has existed throughout history by hiding behind ideologies. It doesn’t really matter what the ideology is and similarly, Cavaradossi, I don’t think he really cares about any of this stuff. But he has that moment of hiding himself also, because he feels he is standing up, because there is an ideology he stands for–or you are a rebel and you speak to who he is as a person. This actually is kind of how people divide themselves nowadays–I’m this type of person. Or, well that vaguely chimes with who I think I am. Or, I’m kind of blue and progressive. Or that detail, like whether I actually agree with what they say doesn’t really matter–they’re my team. And so, I’ve always found the framing of this interesting in the opera but it seems, I think it’s an interesting device that gives them a shield so many need in life to explain their behaviors.

JI: You see politicians who at the end of their speech will say “let’s pray” and it feels very foreign but they’re using religion as something, well and this goes back in history and is what Scarpia represents–the church. The ‘Te Deum’ represents all of the people of Rome and they’re saying in theory we are with you, Scarpia, even though he is what they are all cheering against. And so what’s interesting about the protest signs used in this production is to ask the question of “what is it that we are protesting?” What’s behind what we are protesting? Who’s right and who’s wrong? I don’t think there’s a right or wrong. We have opinions and we rally around–just like the past few months here in Canada, we’ve been rallying around Canada. We use “Made in Canada” slogans and “Elbows Up,” which is to say we are supporting one another. I don’t know if there is a right or wrong, but it’s important to present it.

OW: Were the images used on the protest signs during last night’s performance meant to be vague protest images or were they from some specific event?

JI: There are some specific ones, but yea you’d have to zoom in to see. They’re very contemporary as opposed to the projections. Well, the projections are contemporary but we are dealing with a real life story, an opera set in the 1800s as well. But these are real places and a real moment in history.

OW: Joel, I’d love to know about the highlights of your role as Artistic Director of Edmonton Opera.

JI: Mentoring young artists is a big part of what I have done and giving hope to young singers in terms of this industry is always going to be here, it will probably always look a little different. But, how can we give them the opportunity? And say, hey, stick with it because you’re valued. This country values you and you’re really good. We have the whole cast, the three roles we are switching up tonight and they’re giving a whole performance with the orchestra. They are really good and so how do you inspire confidence in them and pay respect to these traditional pieces, but also how do we move the art form forward at the same time? We can’t commission 50 operas a year because opera is expensive. But we’ve commissioned a new Indigenous opera this year and it’s important for Canadian composers as well to say, hey I’ve got this awesome gig coming up, and that’s furthering their development and career and how to write operas, which is not an easy thing to do as well. This is what it is about and I love the international industry that we have but it’s also a question of how do we push this national awareness.

AS: This opera is going to Whitehorse, Yukon. (Following the two sold-out performances in Ottawa, a second all-Canadian cast from the Emerging Artist Program, led by rising soprano Leila Kirves, is bringing “Tosca” to Canada’s North for a one-night-only performance at the Yukon Arts Centre in Whitehorse, Yukon, on September 20, marking the first opera staged in Whitehorse in more than 50 years. The production will also travel to Canada’s prairies for a performance with the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, on September 27. Some members of the Emerging Artist Program also rounded out the Ottawa cast, playing some of the more minor roles.) It’s been since the 1960s since this has happened, but it’s been around 80 to 90 years since an orchestra has done something like this there and I wish I was going to be there.

JI: This is another big part of how the NAC is keen on having this extension made possible in Yukon and Saskatchewan.

AS: Will you work with the Assistant Directors there? Will they lead based on your support?

JI: Exactly, I’m going to try and get the Assistant Director to make decisions and be with her to see how that is supported and she will run the calls in Saskatoon. That’s the thing, when you have a lot more experience, it’s easy to make those calls. When I was growing up I wish I had someone just to guide me. Part of life is that you see that a bit in like these Star Wars tv franchises where they give these opportunities to help people along. We need more of that in this industry.

OW: When working with emerging singers especially what is your process when cultivating and nurturing their talent? How do you lead them forward successfully?

JI: I think it’s about obviously supporting them as much as you can, giving them as much time, but also letting them absorb by watching and shadowing. That’s one thing. But then putting them on their feet and letting them make their own mistakes and correct them. There was a moment when working with Ailyn Pérez and having Leila Kirves watch what Ailyn was doing in her physical gestures, like with her shoulders, she was singing out to the audience because she wanted everyone to hear her. It’s about being consciously aware in moments like this. Ailyn was supportive of that and vice versa. It’s not a competition about who is going to sing the role better.

AS: It was also interesting how Leila was not trying to mimic Ailyn in how she moves and plays the role. Leila is confident that she is herself and it’s lovely to see how she’s doing it so beautifully.

We have a wonderful resident conductor here, Henry Kennedy, who will conduct tonight’s performance. There’s a wonderful conductor, Judith Yan, who will conduct the performance in Yukon and Saskatoon as well. Henry did the first week of rehearsals here. (He first appeared in Italy in December 2021, following his participation in the Riccardo Muti Italian Opera Academy, which was filmed in Milan by RAI. Invited to substitute for Riccardo Muti, he conducted scenes from Verdi’s Nabucco at concerts in Rimini and Ravenna with the Orchestra Giovanile Luigi Cherubini, which joined him again for “Tosca.”)

JI: It’s also about making time for these singers to sing with the orchestra which is invaluable. It’s nearly impossible to just book an orchestra for yourself. So, this is a way to give them what they need and for Alexander to make time for this is incredible. The singers are on cloud nine and just loving it.

AS: They were beautifully prepared. They’ve taken the opportunity and it’s very impressive.

JI: Leila even sent a bouquet of flowers to Ailyn to say thank you for that support and Ailyn loves the opera and wants to support Leila. It’s really cool to see moments like this.

OW: I also really enjoyed seeing the chorus on stage, engaging with the musicians and soloists. How did you configure where to put everyone when everyone was on stage at the same time?

JI: It was in week one when we looked at the ground plan and where the orchestra was going to be on stage and where the risers would fit, and we have 63 people in our chorus so we had to really plan for it strategically. Instead of setting it, we just asked the question of where we could put people, and it’s scary getting close to musicians actively playing very delicate instruments.

AS: The majority of the singers are members of the community here. They sing in the Ewashko Singers ensemble and are really beautifully prepared. But it’s a difficult thing if you’re not accustomed to it. You are sort of running on stage to Puccini’s score and some guy on a camera is pointing a finger at you (meaning the conductor was live streamed, using a television at the back of the hall for singers at the front of the stage to see his cues in real time). The timing is hard but they did a beautiful job.

JI: Yes, the whole conductor behind the chorus is a whole thing.

AS: Yes, it comes off as weird and sometimes it’s hard to hear what’s going on. I watched the first film of Star Wars with my kids recently and remember when Luke Skywalker is trying to use a light-saber for the first time and Obi-Wan says to put the helmet on and the screen down. And I’m like, this is what we have to do. You have to listen to the space and guess the right moment. Also, you have the option as a conductor to give in to the score, but that takes out all the space for the singers to really place it and you don’t want to force singers. But it’s fun to figure out.

OW: The ending of the opera, which everyone always wants to know in regards to a semi-staged “Tosca” especially, was effective. How did you come up with the idea?

JI: We knew there would be some kind of effect with lightning and something, and that came together very organically towards the end with the question of “what if?” We just tried out this ending and it felt very magical and very fitting in the same way. So, I think it works very well for what it is. This is what I love about these types of things that are more interpretive than finite.

OW: What did the white sheet that Tosca held up before she jumped signify? Innocence?

JI: Exactly. A lot of heroines in these early operas are the only female character in the entire opera which is not the best representation and so it’s about how to give her strength in a moment of her leading the way.

OW: Alex, in knowing this is your final season here with NACO, what have been some of your most memorable take-aways?

AS: There have been many special experiences, for example in my first season (2015-16) we built a project that led into the sesquicentennial celebration of Canada’s confederation. I remember visiting with the then Managing Director of the orchestra, Christopher Deacon, who is now the CEO of NAC, about how we celebrate Canada’s 150th anniversary. We did a lot of reading and thinking about what this meant. We ended up coalescing around four stories. One was by Alice Munro called “Dear Life,” it’s a short story that she had only recently written. It refers to her childhood of growing up in rural Ontario. Another story was a poem by a Mi’kmaw elder and poet Rita Joe, C.M. called “I Lost My Talk,” which described her experience at Schubenacadie Residential School in Nova Scotia here and around the time that the Truth of Reconciliation was happening. (The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada was established in 2008 to document the history and devastating impacts of the Canadian residential school system on Indigenous peoples.) The third story was by Amanda Todd who was cyberbullied and had to move communities several times and ultimately ended up making a YouTube video set to a ten minute musical soundtrack where she held up these cue cards describing what happened to her. As her mother, Carol, says she bounded downstairs after doing it in a cathartic moment and tragically, just a few weeks later, took her own life. It became a big international story about the dangers of online. The fourth story was by Roberta Bondar, the neuroscientist who became the first Canadian woman in space. We felt that each of those stories was both universal and rooted in Canadian communities. We thought we’d explore those and we created a show called “Life Reflected.” We commissioned four new scores around these four stories and worked with Donne Feore to create a multimedia show. This was a wonderful experience in and of itself, working in the deep end of Canadian creatives. We then took “I Lost My Talk” to Rita Joe’s community and built a relationship with them and her family on the reservation and then we took that to Eskasoni and performed music around it. They held a feast with music and welcomed us with performances the night before we performed. The whole community celebrated. The next day they had cleared the hockey arena and put in hundreds of chairs and we became the first orchestra to perform on a Canadian First Nation. For me to be welcomed like that, someone coming from London, England, was breathtaking. Traveling to these communities that have their own culture and their own music and finding a way to connect and share is a human urge through sound that articulates something in here (touches his chest). Being able to have this human connection is the most beautiful human experience. I’m not sure I would’ve had this privilege otherwise and so I would say this is THE highlight of my time with the NACO.

OW: Is there anything you two want me to add that hasn’t been mentioned yet in this interview?

JI: I think more orchestras should explore opera more and how it’s done.

AS: I also want to mention how we brought back opera every other season here in one way or another. Behind the scenes here, this is a G7 capital. How do we not have opera in this city? We all know opera is a crazy business that makes absolutely no sense whatsoever and is a serious human endeavor. There are all the reasons not to do it. But there are ALL the reasons to do it. Look at the faces in the audience, look at the numbers of audience members who attend, look at the stories that we’ve told for hundreds of years across cultures, across languages and different styles of music through this ultimate art form. If we can, as a national capital, re-engage with this conversation about how to make opera a more regular experience here, I feel it will be a really positive outcome. I would advocate for this.

JI: There are so many great composers that aren’t necessarily in the orchestral repertoire because they only wrote operas.

AS: By the way, the composer who wrote the opera that Joel will be premiering, Ian Cusson, is a brilliant composer. The living opera is also here. The opera of today and tomorrow is alive in Canada, with directors like this as well.

OW: Joel, tell me more about this opera.

JI: It’s based on a novel called “Indians on Vacation” about a middle-aged Indigenous couple who travel to Prague and he’s dealing with health issues, mental health issues, so I think it’s not unfamiliar to a lot of people that may be going through something similar. It’s about the relationship he has with these sort of voices in his head, or demons. They put him down or tell him things, and I think it’s a very normal thing but it also touches on our past. It’s a comedy and this is the only Indigenous comedic opera that has been written.

AS: It’s similar to what we did in “Life Reflected,” where we didn’t just want to hit Canada on the nose but instead to come in with a story and events and all the complexities of human experience that could be transposed anyway. But it’s also a Canadian story and this is a lovely access point for a lot of people.

Who adapted the text?

JI: Royce Vavrek adapted the text for it. He’s from Alberta originally, so this is great. We will have an understudy cast as well, and almost all the singers are Indigenous and so, classical Indigenous singers also need support and access that they may not have based on the systems.

The Edmonton Opera’s Emerging Artist Program also gives space and support to the stage management, technical, and design side of opera production. Opera is this elusive thing because there are so few opportunities to be involved with it. So, part of our program is also the mentorship and training on that side as well, so they’re capable of running the show. It’s important to give them an experience that makes sure they’re supported, even when mistakes are bound to happen, but how to give them that support and just the experience overall. It’s not just singers, but all facets that weren’t always there, as well.

AS: Yes, this is an important institution. Henry, I have such a growing admiration for him, he’s already growing into the role as a fabulous musician and he’s using the opportunity and building a great connection with the orchestra. There are some individuals when you see spaces opened up they really own it, and you know the next thing they go into.

JI: You can open doors, but they have to walk through it. And some do and some don’t. But this you can’t predict, you can’t know. But that’s the next thing. You can open doors for people and how they respond to that, especially when someone just thrives, is so incredibly rewarding. To see who takes off and you just support them through it.