Page to Opera Stage: Wilde’s and Strauss’ Scandals with ‘Salome’

By Carmen Paddock“Page to Opera Stage” looks at stories – real-life or fiction, old and new – that have inspired operas, and the ways these narratives have been edited and dramatized to fit a new medium. This week, we look at a theatrical work adapted for opera: Oscar Wilde’s often-banned “Salome” and Richard Strauss’ no-less-controversial operatic reworking.

Over the past few weeks, this column has looked at novels, novellas, and poems that have been transformed for the operatic medium. In this and some following explorations, the transposition is more of a lateral move – from the theatres of Europe to their operatic stages. And in the case of Oscar Wilde, Richard Strauss, and a section of the New Testament, these words, characters, and plot are virtually unchanged.

Today, “Salome” – the tale of the Judean princess, stepdaughter of Herod, who becomes enamored of John the Baptist and demands his head – is far better known in its opera form than in its original play format. This is in no small part due to Wilde’s unorthodox authorship and censors barring early productions across Europe. Wilde was known as a critic but not as a playwright when he began work on his Biblical reworking in 1891. By some accounts, he had been considering the subject since his undergraduate days at Oxford. Wilde, never one to do things by halves, had not yet had a play on the English stage and challenged himself to write “Salome” in his second language – French. He explains his reasons in an 1892 publication.

I have one instrument that I know I can command, and that is the English language. There was another instrument to which I had listened all my life, and I wanted once to touch this new instrument to see whether I could make any beautiful thing out of it. The play was written in Paris some six months ago, where I read it to some young poets, who admired it immensely. Of course, there are modes of expression that a Frenchman of letters would not have used, but they give a certain relief or colour to the play.

Wilde’s French was idiosyncratic, lending the play a declamatory feel and an added exoticism to the scandalous material. An English translation was completed by Lord Alfred Douglas (“Bosie”), which was widely edited and revised by Wilde prior to its 1894 English publication. The playwright initially wrote “Salome” with Sarah Bernhardt in mind for the leading role but the play was shut down by the Lord Chamberlain, who acted as the theatrical censor. Bernhardt vowed to perform the role in Paris – and Wilde published the play in France in 1893.

Unfortunately. Wilde never saw a production of his cause célèbre. He was imprisoned for homosexuality – tragically on the information provided by Bosie’s father – when the first theatrical production was mounted in Paris by the Théâtre de l’Œuvre. Wilde had been dead for two years by the time Richard Strauss saw “Salome” performed in Berlin in Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation.

Strauss immediately set about composing an opera, using Lachmann’s translation as the libretto but cutting roughly half of the text. The result is a dialogue-based libretto, where conversations flow without aria structures but recurring rhetorical and melodic devices lend the story continuity. As Salome progresses through each of her requests, refusals, and professions of love/lust, each appears three times with success or capitulation appearing at the third repetition. This pattern lends an order and inevitability to the proceedings: these characters are unwise and unwieldy, and a block will only engender more vehement desire.

Thematically and textually, Wilde and Strauss are separated by language and length but little else. Strauss’ music, however, adds added pressure and dissonance underscoring the unnatural, animalistic lusts at its core. He utilises leitmotifs, specific key signatures, and distinct instrumentation for different characters and plot points (for instance, the tambourine at every mention of Salome’s dance), but scholars throughout the 20th century have not agreed on the meanings of their different modulations. This lack of prescription clouds character motivations and opens the story up to many different readings.

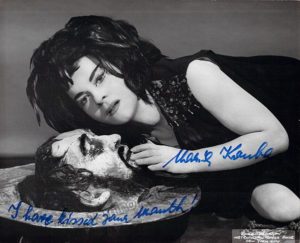

Strauss, a composer who often lent towards the self-indulgent and philosophical, here uses polytonality and chromaticism in his dense, lush orchestrations to drive up the tension. The opera usually runs around 100 minutes, leaving no room for narrative bloat. Much has been written about the famous chord – a A dominant seventh mixed with a higher F-sharp major chord – as Salome kisses Jochanaan’s severed head, but the build-up to its “epoch-making dissonance” is no less thrilling and engrossing. As Wilde himself said, his play has “refrains whose recurring motifs make it so like a piece of music and bind it together as a ballad.” One imagines his likely pleasure at Strauss’ homage.

On the operatic stage, “Salome” has had a longer, higher profile place but no less controversy in its first years. The original Salome at the opera’s Dresden premiere, Marie Wittich, refused to perform the Dance of the Seven Veils due to its scurrilous context. Thus began the common practice of a dancer stepping in for the prima donna in this section (a choice that breaks dramatic continuity but allows neither dramatic soprano voice nor movement to be compromised in performance). Olive Fremsted continued this practice at the Metropolitan Opera’s United States premiere; this run was cut short due to discomfort around the story. Strauss’s reported favorite, however, was Finnish soprano Aino Ackté; she both sang the role and performed the dance. In 21st-century performances temporarily replacing the soprano with a dancer is less and less common, making Salome a fiendishly difficult role to cast.

As modern mores around irreverent and perhaps sacrilegious Biblical stories on stage and screen have relaxed, “Salome” has enjoyed a less scandalous and equally high-profile place in the operatic canon. Preserving Wilde’s text (albeit in translation) and adding some of Strauss’s most finely constructed music-drama, the story of a princess obsessed to the point of bloodshed still retains its unsettling power.

Categories

Special Features