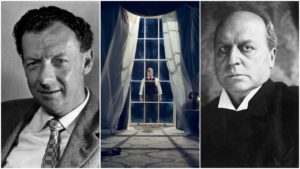

Page to Opera Stage: The Subtle Thematic Shifts Britten Makes In His Adaptation of Henry James’ ‘The Turn of the Screw’

By Carmen Paddock“Page to Stage” looks at stories – real-life or fiction, old and new – that have inspired operas, and the ways these narratives have been edited and dramatized to fit a new medium. This second instalment looks at Henry James’ and Benjamin Britten’s “The Turn of the Screw.”

A governess is hired to look after two children by a distant uncle on the condition that she never contact him. Upon arriving at Bly Manor, she finds housekeeper Mrs. Grose and children Flora and Miles a delight – but soon, she notices odd behaviors, hides Miles’ dismissal from school, and thinks she sees a man and woman lurking around the grounds. She describes her fears to Mrs. Grose, who recognizes the description of Peter Quint and Miss Jessel. But the former manservant and governess are dead – recently dead by misadventure and suicide. The governess, increasingly distressed by these apparitions and the children’s erratic behavior, confronts Flora and causes the girl’s nervous breakdown. She then confronts Miles, who denies involvement in the spirits but at the last moment seems to see something, shouts “Peter Quint—you devil!” – and dies.

Few novellas have undergone the range of critical interpretations and reinterpretations as has Henry James’ 1898 ghost story “The Turn of the Screw.” In an odd way, it is not surprising – the story of a haunted mansion and its inhabitants was written by the cousin of William James, the “Father of American psychology,” a contemporary of Freud, and the founder of functional psychology and pragmatism. Perhaps an era of such interest in and nascent understanding of the human heart and mind made for fertile literary ground.

At any rate, the material is ripe for psychological and subtextual investigation and reanalysis. James’ ghost story is deliberately ambiguous, notably regarding the Governess’ reliability as a narrator and the nature of the ghosts. Are they real? Are they present but unseen? Are they figments of the Governess’ imagination, and is she the real danger to the children? To paraphrase Benjamin Britten’s operatic prologue, it is a curious story indeed.

After a commission from the Venice Biennale, Britten and his librettist Myfanwy Piper adapted the novella into a two-act opera consisting of a prologue and sixteen scenes in 1954. It is one of Britten’s most explicitly atonal operas, with a variation of the twelve-tone “Screw” theme opening each scene. The beauty of the chamber work – scored for six singers and 13 instruments – is that it is as open to interpretation as the source material.

Its premiere came 20 years after the literary critic Edmund Wilson had suggested that the governess’ sexual repression causes her to hallucinate the ghosts, and many interpretations of the opera have leaned into such psychoanalytic readings. But more modern understandings of psychology and trauma, class (the children of the gentry and their working-class caregivers), and pure supernatural scares offer equally valid re-readings of the original and adapted texts.

As each reader has their opinion of James, each singer and production can take Britten’s and Piper’s libretto in many directions, making “The Turn of the Screw” an exciting adaptation to continually re-adapt. The novel is told through the point of view of the Governess as found in papers she left behind – a conceit the prologue of the opera borrows – but the opera allows several other characters to take the lead in the storytelling. However, the one choice that the libretto makes is the existence and at-least-partial visibility of the ghosts. Not all characters always have to see them when they are present on stage, and some characters may never see them depending on the production, but there is no doubt that they are there and hell-bent on the children’s souls.

This choice is cemented in Act two Scene one, when the ghosts confront each other about their sins in life while the house sleeps.

MISS JESSEL

Why did you call me

from my schoolroom dreams?

QUINT

I call? Not I!

You heard the terrible sound

of the wild swan’s wings.

MISS JESSEL

Cruel!

Why did you beckon me to your side?

QUINT

I beckon? No, not I!

Your beating heart to your own

passions lied.

The unholy pair clearly have unfinished business with each other, entirely separate from the humans they plan to ensnare – something that reads as quite autonomous and separate from the Governess’ or children’s imaginations. The children, though, are not far from the ghost’s minds. Each is clear in their desire for a young victim to follow them in their exile.

QUINT

I seek a friend –

Obedient to follow where I lead,

slick as a juggler’s mate

to catch my thought,

proud, curious, agile, he shall feed

my mounting power.

Then to his bright subservience

I’ll expound

the desperate passions

of a haunted heart,

and in that hour

“The ceremony

of innocence is drowned”

MISS JESSEL

I too must have a soul to share my woe.

Despised, betrayed,

unwanted she must go

forever to my joyless spirit bound,

“The ceremony

of innocence is drowned”

The quotation is not from James but from W. B. Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming.” Yeats’ poem was written in the aftermath of World War I and the influenza pandemic, and its dreamlike lines are often found in songs and titles (such as Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart” and Joan Didion’s “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”). While the poem pre-dates his semi-occult book “A Vision,” which he claimed he and his wife wrote through automatic writing, much imagery overlaps – and the psychic and unconscious themes tie into the ghosts of James and Britten.

The composer’s inclusion of the “ceremony of innocence” line also emphasizes his favorite theme of the loss of innocence – here, a loss intentional and unimagined. Through this, Flora’s breakdown at interrogation by the Governess can be seen as a manifestation of this that she does not have the words for, and Miles’ death in defiance of Quint is the ultimate price to fight off this corruption. Again, these are possible readings, but it is hard to imagine Peter Quint and Miss Jessel merely figments of an overactive imagination when they are such unforgettable vessels for theme and narrative.

Quotes from Piper’s libretto and the Project Gutenberg text of “The Turn of the Screw.”

Categories

Special Features