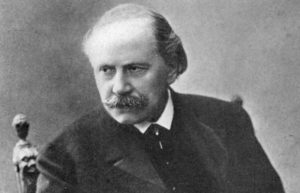

Jules Massenet was born on May 12, 1842 and would go on to become arguably the most impactful French composer of the Romantic era. When we look at the standard repertory, Massenet’s place is firmly locked in with two of his works among the greatest ever created.

In celebration of his birthday, some of our writers came together to muse on their personal favorites by the composer. While his repertory is rather varied and unique, you’ll notice that some familiar titles prevailed.

John Carroll – Manon

Manon” is not only my favorite Massenet work, but one of my top-choice operas of all time. It’s just so perfectly and utterly French! So many of the most famous operas by French composers are not truly French to their core because they are set in other parts of the world. Think about it: “Carmen” is set in Spain; “Werther,” “Faust”, and “Mignon” are set in Germany, and “Les Contes d’Hoffmann” in Bavaria; “Thais” in Egypt;“Lakmé” in India; “Roméo et Juliette” in Italy; “Les pêcheurs de perles” in Sri Lanka; “Samson et Dalila,” “Les Troyens,” and “Orphée et Eurydice” in Antiquity; and the list goes on. Though these librettos are in French and the music has all the telltale signs of French composition, something about the distant cultural settings imbues these works with non-Gallic influences (and rightly so).

“Manon” is set in and around 19th century Paris so is as gloriously French as can be. Massenet’s exquisitely crafted score is a marvel — a continuous series of beautifully judged moments that connect into a sweeping story of a passionate relationship between two young lovers, clearly meant to be together yet never quite in sync for long. The score feels like a long duet between Manon and Des Grieux as they have full duets or shared scenes in all five acts. Interspersed among these are spotlight solos for both lovers that reveal their inner thoughts or struggles, especially Manon who has eight arias or significant solos. With a fine balance of intimacy and virtuosity, sentiment and flair, empathy and narcissism, Massenet’s Manon is quite a role. What’s more, beyond the two incredible leading characters who rightly dominate the show, the score has so much color and character, it’s downright cinematic.

PS: I want to put in a special honorable mention for Massenet’s exquisite “Cendrillon”— in my view its lush, delightful score and charming take on the classic Cinderella tale are criminally undervalued.

Greg Moomjy – Manon

In the 1890s as Puccini was working on “Manon Lescaut,” he was asked why he was writing an opera about “Manon” if Massenet had just written an opera based on the same subject in 1884. His response was that Massenet wrote the story as a Frenchmen and he would treat it as Italian. While this may be rather vague, I believe that the two versions are very different and Massenet’s is far better.

To begin with, the sound world he creates perfectly captures the atmosphere of mid-18th century France. It not only riffs on 18th century musical forms like Manon’s Gavotte and the Ballet Suite, but it also captures the joie-de-vivre of the French upper crust prior to the revolution. You hear this from the first notes of the Overture which are repeated in the opening to the Cours-la-Reine scene. The other part of this equation lies in Massenet’s treatment of Manon herself. His version is more complex and sympathetic than the femme fatale who needs to be punished by dying in the wilderness of Louisana. Despite dying young, Manon lives a very full life and unlike in Puccini, she’s able to finally strike a balance between her desire for money and the honest love of a young man.

In Massenet, Manon’s tragedy is not that the two forces that drive her can never meet, it’s that when they do meet, it doesn’t last very long and she still dies young. Furthermore, throughout the course of Massenet’s opera, she acquires a worldly wisdom which gives her the ability to know when her drive for love and riches goes too far. Additionally, the French version calls for a greater cast of characters and this allows for Manon to interact with society. Consequently, the audience understands her need for power and position because that was how French society measured success. She is, therefore, more than just a heartless femme fatale.

Lastly, Manon offers prime examples of Massenet’s so-called conversational melodies, which is used particularly well in Manon’s Act one entrance aria. Here the lush romantic melody is briefly broken off when she tells her cousin that many times during her journey she would laugh without knowing why. This line of text is mostly spoken as if she was laughing it off, but it is kept with a gorgeous trill, which perfectly captures Manon’s youthful spirit and defines her for the rest of the opera.

Sophia Lambton – Werther

A premonition of the unearthly events (and ensuing portentous music) of the twentieth century, the date of Werther’s writing flummoxes its listeners. With perseverative, tempestuous tremolos on the strings percolating the opera, most of its eerie passages foretell catastrophes of World War I over two decades prior to the fateful shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand; it pits jocose children’s singing portentously against unexpected minor-key intervals on strings to create a surreal, Brechtian palette of music one might only expect to derive from the fifties.

The shocking facet of Werther is not that it centers on a young man in love with a married and (sadly) virtuous woman who eventually takes his life as a result. That part we’ve seen and heard before; the work’s originating novel by Goethe was written in 1774. It’s that, in contrast to most deaths and suicides across the spectrum of Romantic opera, the frenzied, incessant underpinning of the motif that foresees Werther’s death is less a musical device than it’s an inescapable, harsh rumination on the value of life and the essence of existentialism. Long before the births of Jean Cocteau and Albert Camus, Massenet’s music seems to ponder the purpose not only of living when one’s love is away, but of playing with children, of staying faithful to one’s husband, of celebrating the haunting “Noël, Noël, Noël.”

Unlike most cursed heroes of opera, who are either a victim of fate (take your pick) or their own self-defeating character (Tchaikovsky’s obsessive Herman in Queen of Spades; even his lackadaisical, perpetually bored Eugene Onegin), Werther is emblematic of the precarious nature of life itself: a man who questions why he’s here. Most productions of the opera will wrap up their sets in spells of choking snow, extrapolating symbols of the work’s dismal end from the start. Although the later “Tosca” and “Madama Butterfly” will make their own use of intimidating, menacing motifs, they won’t be left in their bare state for long: soon enough another luscious, innocuous melody will wrap them up in a protective blanket to disguise the imminent moroseness. In “Werther,” the tragedy of life itself – Werther’s, Charlotte’s, even the fifteen-year-old Sophie who naïvely thinks that Christmas will forever be the annual highlight of her life – is palpable and resonant throughout. Despite the different voices, themes and keys used to paint them, it is a work that has no hero, villain or even damsel in distress. The mystery of life is the antagonist, and we the audience are tasked with sensing its inevitable horrors from its bleak start to its hopelessly prognosticated end.

David Salazar – Werther

What makes Massenet’s “Werther” such a veritable masterwork is how the composer juxtaposes the increasingly self-immolating emotions of its titular character with a general ease and calm everywhere else. Children open the opera with chants of “Noël” and at the end of the work, with Werther dying, we hear the young ones continuing their innocent behavior. Sophie becomes a personification of this chorus of children throughout the opera, providing brightness and spark to the darker musical movements of the titular character his beloved.

What makes this so effective is how it continually offers a reminder to the audience that Werther may in fact find some hope and that his tragedy is the result of his own inability to adapt. He destroys himself, not the world. There is still beauty in nature, as he adeptly states during his first aria moments after the opera opens. But more importantly, Werther, an adult, creates the complications in his life while more innocent beings simply rejoice in the world around them.

But Werther isn’t the only one to complicate matters for himself. While in the original work by Goethe Charlotte’s feelings are never accessible to the reader, Massenet allows the audience an opportunity to explore her own confusion of emotions. She reveals her love for him at the end, but the audience can already sense it because Massenet’s music hints at it repeatedly. This ambiguity adds to the tension of the story and amplifies the tragedy that much more.

The music itself is full of glorious melodies and Werther’s several solo moments only seem to build on top of one antoher, each more desperate than the last. Even if you struggle to empathize with Werther’s reasoning and behavior, the music does the heavy lifting when it comes to making you empathize with his feelings. And it never lets up. When the ending of the work comes around, you feel that you’ve gone through a devastating experience. One that simply won’t leave you.

Francisco Salazar – Manon

To pick a favorite Massenet opera is a difficult task. He’s a shapeshifter of sorts with each work having its own musical style to suit its narrative. “Werther” has such passionate music while a work like “Thaïs” is more restrained and in many ways very formal. “Cendrillon” is jovial and playful and some of the other works like “Hériodade” and “Le Cid” hue closer to the French grand opera structure. Few composers have ever exhibited the versatility that became Massenet’s signature.

But “Manon” sticks out for me because it is both grand opera, but the most intimate of works as well. Massenet gives some of his most tender and passionate music to des Grieux, contrasting him with the ever-complex Manon. Her music has a playful touch at the beginning followed by a flirtatious quality in the second act. Her Cours-de-la-reine scene adds sexual tension, which morphs into unrestrained passion in Saint-Suplice. The fourth act is a masterpiece as it juxtaposes Manon’s passion and sensuality in the opening trio before exhibiting a more banal nature in her ensuing aria. Moments later we see Manon’s suffering during the final concertato. We truly get it all.

While the opera is lengthy, Massenet always keeps the music unpredictable, mixing a vast color palette from one scene to the next. From gavottes and miniatures to impassioned and intense ensembles, it’s a work of irresistible nature.