Opera Zurich 2019-20 Review: Arabella

Robert Carsen Relocates Strauss’ Light Opera to The Third Reich and Uncovers its Deeper Themes

By Alan Neilson(Photo: T+T Fotografie / Toni Suter + Tanja Dorendorf)

Vienna in the 1860s was a period of change, of unrest. Whilst the armies of the Empire had suffered numerous military defeats throughout the 1850s and 60s, its Emperor Franz Joseph undertook a programme of works aimed at modernising the imperial city: the city walls were demolished and the Ringstrasse completed, along which were built the many magnificent buildings which dominate the city today, including the opera house, parliament and town hall. It was a time in which fortunes were there to be made, but it was also a city living beyond its means and during periods of such feverish change there are bound to be casualties.

It was against this background that Strauss sets his opera “Arabella,” of which the Waldner family, around which the drama turns, is one of its losers. Unlike in “Der Rosenkavalier,” to which it is often unfavorably compared, this was not a self-contented society, but an uncertain, even vulgar one.

Nazi Control

For Zurich Opera’s production of “Arabella,” the director Robert Carsen decided to focus his attention on this wider context, highlighting the anxiety and uncertainty brought about by large scale change in a world in which values clash, where social and economic relationships are in a state of flux, the old accepted formulations are under threat, and in which the comfortable lifestyle of the Waldner family hangs in the balance. Rather than setting the work in the Vienna of the 1860s or even of 1933, the year of its composition, also a time of change and upheaval in which the country had lost its empire, the world was in the midst of the Great Depression and in both Germany and Austria Nazism was on the march, Carsen opted to move the drama forward to post-Anschluss Austria, a time in which Vienna was under the firm control of the Nazi jackboot, one which is more clearly connected in the minds of the audience with a society riven with anxiety, fear, loss and opportunity.

And it proved to be an inspired decision, one which enabled Carsen to successfully develop the drama in a coherent, dramatically gripping manner, which captured the usually ignored deeper themes embedded within the work. It was also a reading which elevated it above the sentimental folksy work with which the opera is often tagged, and at the same time significantly distanced itself from “Der RosenKavalier.”

Carsen and his stage designer Gideon Davey took every opportunity to insert the Nazi presence into staging ensuring the audience was aware of context and consequent underlying tensions.

The hotel lobby, the primary location for the work, was populated by the usual suspects, intermingled with soldiers in Nazi uniform. Arabella’s three suitors Elemer, Dominik and Lamoral are members of the SS, which cast a sinister shadow over their behavior, especially when Elemer, angered by Arabella’s rejection inveighs against Mandryka, a Croat, an outsider, “You’ve fallen for that stranger from Wallachia, or wherever he is from!”

The Act two coachmen’s ball is turned into an opportunity to display Nazi power, with swastikas draped from the sides. As the final curtain falls on Arabella and Madryka’s reconciliation, German soldiers rush onto the stage, guns in hand. It is payback time, the message is clear: you cannot take up with an outsider and expect to walk free!

In fact, the portrayal of Mandryka was expertly crafted. Within the context of Third Reich he is no longer the simple exotic foreigner, his differences are far more pertinent and far more dangerous, he is separate from the rest, less than the rest. He was portrayed as raw and always socially askew, he did not fit in. His hair was long. He mixes his native costume with sophisticated Viennese dress, and his behavior when he loses control is sneeringly condemned. He is not at home in this society, and is made to feel so, and in the process his erratic behavior becomes easily believable.

Each aspect of the drama slipped neatly into Carsen’s vision, so that even the Faikermille whose presence can often have a jarring effect, was seamlessly integrated. The Third Reich is not known for its cultural sophistication, and the mixing of the brash and the gauche with higher forms without discrimination was more the norm. The Faikermille, in this case accompanied by Bavarian peasant dancers, presents herself as a commonplace example of the vulgar underbelly of the regime’s tastes as she enjoys her folkish yodelling and crude behavior, as she frolicked with the guests at the ball.

Carsen also took the opportunity to shine a spotlight on the psychotic and dysfunctional behavior of the regime. During the prelude to Act three, Carsen introduced a dance scene, choreographed by Philippe Giraudeau, in which the dancers dressed as Bavarian peasants and Nazi soldiers indulge in violence and schizophrenic behavior. Although it was clearly aimed at mocking the cult of Nazism, it was simultaneously disturbing and uncomfortable to watch.

The staging was simple but very effective, consisting of a single set, comprising a hotel lobby overlooked by three floors of guest rooms. The entire space was red, which added to the tensions and sense of danger, as well as the heated emotions. The style was typical Art Deco, which when added to the formal, the folksy and military costumes created a stage which at times dazzled.

(Credit: T+T Fotografie / Toni Suter + Tanja Dorendorf)

Making the Most of the Opportunity

On the musical side, Fabio Luisi led the Philharmonia Zurich in a wonderfully expressive performance, which captured the twists and turns in the drama expertly. The playing was confident, energetic and bright and when given its head as in the third act prelude the effect was ravishing.

The sound had a rhythmic vitality, charged with eroticism, which drew in the listener. Textures were beautifully revealed. Orchestras under Luisi’s management always play with a high degree of precision and exactitude, occasionally to the detriment of emotional sentiment. Not so here. This was a beautifully balanced performance which whilst not compromising on precision allowed the score’s emotional excesses to flourish.

The soprano Jacquelyn Wagner in the role of Arabella was a last-minute stand in for the indisposed Julia Kleiter, not that this would have been obvious from her confident performance which blended seamlessly into the presentation. Hers was a fairly aloof Arabella, socially confident and fully aware of her effect on men, yet she was also humorous and engaging.

Her voice was nicely suited to the role, possessing a bright, silvery, liquid quality with which she was able to capture the coldness she felt for Matteo as well as the deep love and eroticism of her feelings for Mandryka.

Her duets with Zdenka and Mandryka were the highlights of her performance along with the closing aria to Act one, “Mein Elemer! – das hat so einen sonderbaren” in which she reflects on her various suitors and on the stranger who has captured her attention, her voice blooming wonderfully as she span out long delicate lines, full of passionate longing, fear and doubt in what was a quality performance of contrasting emotions and beauty.

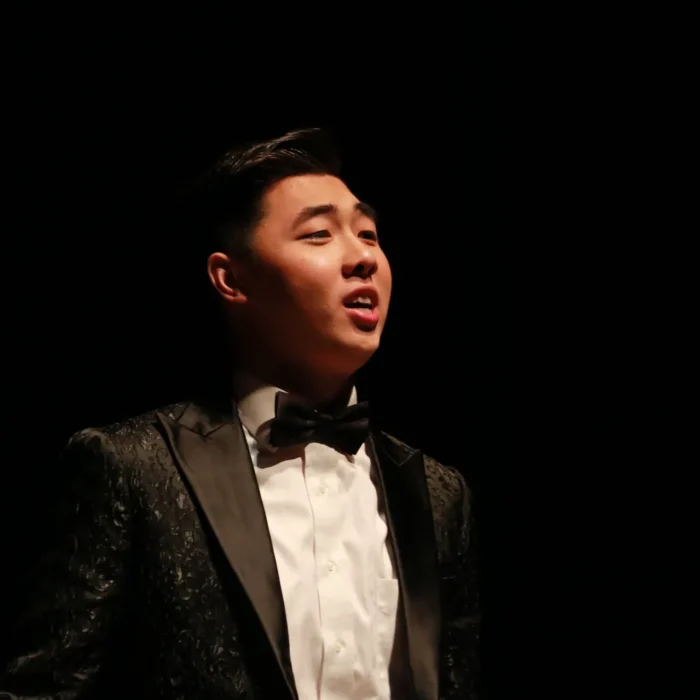

The role Mandryka was parted by bass-baritone Josef Wagner, who provided a lively, detailed and compelling portrait of the rural Croat recently arrived in the cosmopolitan city. He was raw, but chivalrous and fully aware of his own difference. Not only did he successfully look and act out the part of the outsider, but also provided a strong vocal interpretation which captured his changing passions and social unease.

He has a colorful, powerful and flexible voice, which fills out beautifully, underpinned by a natural lyricism. He transitioned between emotional states with apparent ease, yet always realistically so. His Act one aria, “Der Onkel ist dahin,” in which introduces himself to Waldner, talks about his about his estate and forests and his fight with a she bear, and does much to define his character as an unsophisticated country dweller was splendidly wrought with decency, naivety and a definite touch of swagger in the voice.

His duet with Arabella, “Sie wollen mich heiraten” in Act two in which they declare their love for each other was full of passionate intensity, and sung with real beauty, the warmth and depth of his voice embracing and caressing Jacquelyn Wagner’s bright silvery soprano.

(Credit: T+T Fotografie / Toni Suter + Tanja Dorendorf)

Deeper Meaning

Soprano Valentina Farcas was cast as Zdenka whose strong singing and solid acting performance was partially undermined by her costume. There are many ways in which it is possible to dress Arabella’s sister as a man, but having her dress in a dark business suit created the wrong impression; yes, she convinced, but everything she did appeared to be no more than a cold business transaction and had the effect of suppressing the communication of her latent passion, notwithstanding the fact that the style was an accurate representation of the period.

Vocally, however, Farcas produced a clearly defined performance in which her underlying ardour was never in doubt as she span out lines bursting with desire. Her relationship with Arabella was also carefully moulded, the two sister displaying a genuine affection for each other, which was wonderfully depicted in the Act one duet, “Aber der Richtige” in which the two soprano voices entwined beautifully and sympathetically with each other.

Even if Waldner is an irresponsible fellow, prepared to gamble with his family’s security, bass-baritone Michael Hauenstein cut a sympathetic figure as a man whose day had truly passed, unaware of the coming storm, his warm personality and the beguiling timbre of his voice covering his precarious position. It was a super performance, full of detail and expressive subtlety.

The mezzo-soprano Stephanie Houtzeel produced a convincing performance in the role of Adelaide Waldner. Another last minute replacement, this time for the indisposed Judith Schmid, Houtzeel slipped neatly into the part. She was suitably fussy, busying around desperately trying to find solutions to her money and her daughter’s marriage prospects in what was a fine acting interpretation. Vocally, she was equally impressive, her well-supported, expressive voice capturing the underlying anxieties of her character.

Matteo was played by tenor Daniel Behle. Always in a weak position in his pursuit of Arabella he often cut a pathetic figure, but by over-egging the acting he never really convinced, lacking the necessary subtlety. There were, however, no such problems with his singing, in which he used his strong, well-supported voice to characterise the role. His strongest scene was in Act three in which he finally finds the love he has been searching for, with Zdenka, in which his acting, now more relaxed matched his vocal quality, the pleasing timbre of his voice shining brightly.

Anabella’s three suitors, Elemer, Dominik and Lamoral were played by Paul Curievici, Yiriy Hadzetskyy and Daniel Miroslav. All gave convincing performances, but the tenor Curievici in the more substantial of the three roles was particular noteworthy. Singing with confidence he developed his character skilfully as brash, self-centred and full of bravado. The voice is strong and flexible with an appealing tone.

The soprano Aleksandra Kubas-Kruk was a fresh-faced appealing Fiakermilli. She gave a vibrant performance which meandered between the folksy and the crude and vulgar. She acted out the part well, and sang with a bright confidence, in which her yodeling delighted.

It was not by accident that Strauss opened the opera with Adelaide having her fortune read. Things are uncertain and people are looking for hope. The role of the Fortuneteller may be a small one, but it is important in setting the tone of the opera. The role fell to mezzo-soprano Iréné Friedli, who made a very good impression in creating an engaging scene, in which the beauty of the voice was notable.

Musically, this was a wonderful presentation, combining fine singing with excellent playing from the orchestra. What made it stand out, however, was Carsen’s imaginative production which managed to get below the sweet, simple, even vacuous love story that has left many commentators slightly dismissive of the work.

This was an “Arabella” which was given more depth and substance, one in which the behavior of all the characters becomes understandable as complex reactions to the changing nature of the society in which they are living, one based on the fear of a very uncertain future. Moreover, it is an interpretation which is in step with Strauss’ music and of the period in which the opera was originally set.