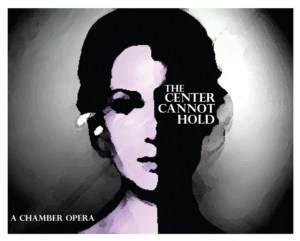

Exploring Mental Health in Kenneth Wells’ ‘The Center Cannot Hold’

By John VandevertOperas about the optimistic sides of mental health seem rare. Of course, we have opera concerning the fall of man and women, the results of a life mired by guilt and anger, the pursuits of love, and the death of loved ones. There are operas about the destruction of the world, the persecution of innocence, and the futility of trying to escape one’s predetermined fate.

There are many operas about the human struggle, the fight to live and not only survive but thrive. Immortal operas like “The Tender Land“ (Aaron Copland), “The Magic Flute” (W. T. Mozart), “Die Frau ohne Schatten“ (Richard Strauss), and “Don Carlos“ (Guiseppe Verdi) are but a few of a huge, and ever expanding, list of operas that depict the human ability of overcoming challenges and difficulties. When it comes to mental health and the stories of psychological manipulation and hardship, however, operas like “Madame Butterfly“ (Giacomo Puccini), “Wozzeck“ (Alban Berg), and “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat“ (Michael Nyman) show us how diverse being human actually looks like.

While opulence and lust, death and drama may excite us, it is the stories that reflect the visceral realism of the human condition that operatic theater is really all about. To celebrate Mental Health Awareness month, let’s look at an opera which puts mental health in a more optimistic light. An opera about overcoming one’s troubles and conquering life itself, Kenneth Wells’ chamber opera “The Center Cannot Hold,” speaks to the internal tenacity of the human spirit to overcome truly difficult conditions.

The Work

Wells’ two-act chamber opera was the brainchild of a collaboration with Dr. Elyn Saks, author of the memoir which the opera was modeled after. Having been invited to speak on a round-table for the premiere of Wells’ first operas, “Eleanour Roosevelt,” the two struck up a relationship. After reading, Wells realized that it was going to be the foundation of his second opera. Saks’ book, published in 2007, was a game changer in the realm of mental health and its relationship to one’s quality of life. A candid reminiscence of her struggles with schizophrenia, the book talks about how she overcame her struggles and became a highly regarded academic and whole person. Saks’ story was then pushed to the mainstream in 2012 thanks to her TED talk, “Mental illness – an insider’s perspective,” where she argued that it was through compassionate thinking that mental struggles can be more fully understood. Having taken the book and created a libretto from it, Wells had the music finalized by 2012 and by July of 2016, the opera was ready to be set onto the operatic stage. Premiered at Louis Jolyon West Auditorium (UCLA) under the directorship of Brendan Harnett and musical directorship of Stephen Karr, the opera has continued to have a performance life until the present day. A part two has been scheduled for this year. The event entitled, “Recovery,” there is a bright future for the opera it seems.

Performed by singers from the Pacific Opera Project, in collaboration with chorus members from both the Los Angeles Opera Company and the Los Angeles Master Chorale, the opera took audiences for a ride by personifying Saks’ split identity as she traversed throughout her student life at Yale University in the late 1970s. The three personas, or stages of life, that the opera dealt with were those form Saks’ experiences being hospitalized during her time at Yale University. First, as the student (sung by Jamie Chamberlin) Saks’ mental health is frustrated leading to her becoming the “Lady of the Charts” (sung by Danielle Marcelle Bond), although ultimately rising above the challenges to become a Professor (sung by Rebecca Sjöwall). A joint project between the Semel Institute Center for Health Services and Society at the University of California, the opera reflects the relationship that Wells holds between science and art. A relation, as he shared in an interview back in the mid-2000s, which stems from his family and their roots in both music and science. With a job that stems in multiple different directions, from a Senior Scientist at RAND to a Professor of Health Services at the UCLA School of Public Health, Kenneth Wells’ second opera, of which there are three now, chose to look at the often taboo subject of mental health and recast its nature. Giving a light to the shadows, the human spirit can overcome.

Relationship to Music

Like many composers, Wells didn’t choose music as his solitary profession and yet had succeeded in creating works of great musical achievement.

Composers like Modest Mussorgsky (Boris Godunov), Alexander Borodin (Prince Igor), and even Antonio Vivaldi (Griselda), have routinely studied one thing and chosen music as their side passion. But equally as common, or perhaps uncommon, is having a family steeped in both scientific pursuits and musical pursuits in equally as vigorous measure. For Wells, this was indeed the case for him growing up. Many of his older family members were busy with their musical lives outside their main profession. Ruth Wells was the first woman thoracic surgeon in the U.S, whereas his paternal grandfather was both steeped in the medical profession and yet at the same time the choir director at International Church of the Foursquare Gospel in California. His grandmother was a semi-professional soprano and his uncle was both a painter and a pianist. Thus, it’s easy to see, much like Samuel Barber and his whole network of family and friends, how music all but fell into his lap as a hobby and semi-serious professional pursuit.

But when it came to composing, he had begun quite young and knew from an early age he wanted to write an opera. As he noted, “My best friend in junior high introduced me to opera recordings, and I decided that someday I would write an opera.” Despite his interest in music, having begun lessons at the age of nine, he pursued a medical path but ultimately found his way back to music over time. He had originally never quite understood why, when it came to opera, that there were so many stories of operatic death, gloom, and destruction of life, “Why couldn’t someone tell a powerful, compelling and entertaining story that lifts us up and gives us hope?” Thus, over time as he grew, this decisive vision stayed with him.

Inspiration and Story

“The Center Cannot Hold’s” primary inspiration was Saks’ life story and her ability to rise from her struggles to become the Professor and academic researcher that she is today. The memoir of Saks could have possibly been written under a false name. However, although encouraged to do so, Saks did not choose to use an alias and instead chose to use her own name. As she noted, “I wanted to open a window into the mind, to bring understanding to people who don’t have schizophrenia and hope to those who do.” Wells, after talking with her and reading her book, knew that this was going to be the theme of his newest opera for a very simple reason, “I’m attracted to turning points.” Clarifying the point, he noted that Saks’ somehow innate ability to modify her methods of dealing with her mental health throughout her life initially attracted him to her story and life.

As a psychiatrist, he has noted that he is fascinated by moments when the human condition changes, “I am impressed with her resolve to withstand all that happened to her and move forward, return to law school and become ‘somebody.” Instead of leaving law school, Saks completed her studies and entered her field, quickly becoming a respected member of the community and a leading researcher of mental health. The opera itself deals with the period of life when she was at Yale University and the process that led her to become hospitalized and the journey to liberate herself from that. Having her personhood split between three characters showed the fragmentation that she felt during this period of her life. Discussing the theme of the opera Wells notes that the opera was about triumph,

“The Center Cannot Hold” is really about falling apart psychologically (i.e., the center cannot hold) and learning that maintaining some degree of control through insight, even if it is an appearance of control, can be the starting point of recovery—coupled with treatment and compassionate support from genuine friendship.

Categories

Special Features