Opera Meets Film: Why Susanne Bier’s ‘After The Wedding’ Would Make For A Perfect Opera

By David SalazarA few months back we took a look at some of the Oscar nominees that could potentially make for strong opera adaptations. Opera has been an artform that has often taken its greatest stories from other artforms. For a while, artists adapted their works from plays or myths. In more recent years, we have seen the development of operas based on longer novels and even movies.

So in continuation of that thought-experiment from the Oscar season, we are going to periodically pick out a film and look at why it might make for a strong operatic adaptation. In theory, any story can work. But some films simply have elements that make for even stronger operatic creations.

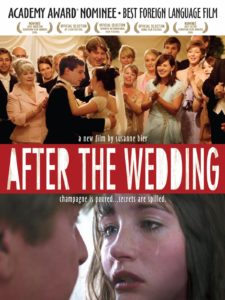

For this week’s installment, we are going to look at Susanne Bier’s masterpiece “After the Wedding,” which was recently adapted into a film featuring Michelle Williams and Julianne Moore. The original was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards in addition to a number of other major accolades.

The Story (SPOILER ALERT)

So what is “After the Wedding” and what makes it strong for potential operatic development.

The original 2006 Danish film by Bier is a potent melodrama about a Jacob, a Dane who is living in India managing an orphanage. He is offered an opportunity to potentially help the orphanage via a business deal in Denmark and is immediately forced to return home to confront his past. There he encounters Jørgen, one of the wealthiest men on the planet (in this film), who seems intent on helping Jacob and being friendly with him. From there, Jacob is invited to the wedding of Jørgen’s daughter where he not only runs into his former lover Helene (who is Jørgen’s wife), but also discovers that their daughter Anna, is actually the child born of Helen and Jacob’s previous relationship.

Jacob confronts Helene about the truth and Anna eventually learns the name of her true father (she knew that Jørgen was not her true father). But, of course, there’s more. Jacob finding out about his long-lost daughter is no coincidence and the entire scheme was masterminded by Jørgen. The reason? He is terminally ill and wants someone to take over for him as the head of the family. He wants Anna (and his twin sons) to have a father, he wants Helene to have a husband, and he wants his empire to have an heir. The reason why he picks Jacob (aside from all the personal links) is because of his selfless projects in India.

The film features a subplot regarding Anna’s failed marriage to Christian, who wants to be the family heir, but ultimately cheats on Anna shortly after marriage. There is also a subplot between Jacob and a young Indian orphan Pramod, who sees him as his father.

Opera’s Archetypes

It’s not hard to imagine a composer like Verdi taking this melodrama and setting it himself as its characters are very much archetypal of the ones he and other composers of his era often wrote about.

Jacob is the outsider with a mysterious past who has exiled himself from his native home. He, in turn, is a hero to another group of outsiders, this time orphans in India. Suddenly he is called back to his home country by a potent ruler, Jørgen, who wants to help him; this powerful figure, despite appearing controlling and antagonistic, is actually conflicted over the future of his kingdom and his family, and is seeking out an heir to take care of those things for him.

This is complicated by the archetypal former lovers with a tumultuous past and the ensuing love triangle that shapes up as a result. Throw in the reunion of a father with his lost child, a shocking and tragic death, and the ultimate conflict of this outsider coming to terms with where his rightful place might be, and you have the thematic ingredients for an opera that could be perfectly set in the medieval times (or any time period for that matter) if you so pleased.

Embedded Structure

All of these themes run throughout the world of opera in different ways. But what makes “After the Wedding” even stronger as a potential operatic source material is the film’s structuring and how it relates to traditional operatic storytelling.

The plot might seem like it winds and grinds the viewer, but the reality is that it only hinges on two major revelations coming to the fore; in between these general lines of action, Bier isolates her characters to allow the audience to have sufficient alone time with each of them, not unlike how the best opera composers have often worked with bringing balance to operas with multiple lead characters. Watch the film with opera in mind and you can already see a lot of how the story itself will unfold from musical-dramatic standpoint.

You have the big wedding as the structural centerpiece and on either side of it, you have two-person scenes full of intense emotional content that would make for strong duets. You have two strangers facing off, with a distrusting Jacob trying to find out what Jørgen is playing at. You have Helene and Jacob confronting each other over their tumultuous and painful past together. And then you have ample opportunity to develop these relationships via similar musical structures, which are pretty much outlined by the film’s own isolated scene structures.

You have a daughter learning of her adoptive father’s death and sharing a moment together to express their love for one another. You have a scene between former lovers as they potentially reconcile with one another and hint that their continued emotions. Jørgen’s big moment at the end of the film as he breaks down over his fate is nothing if not the perfect opportunity for an aria. And if you’re really feeling like utilizing traditional opera structures, there is even a scene for a drinking song, albeit an aggressive and violent one.

It also can’t be overlooked that at its core, the film’s narrative hinges on the relationships of four principal characters – two men and two women; voice types probably wouldn’t be all that difficult to differentiate the characters either.