Opera Meets Film: The State of American Opera in Peter Rosen’s ‘New American Opera’

By John VandevertCurrently, opera in America in a state of unprecedented upheaveal. With the ongoing precarity occurring at the Metropolitan Opera House, from the recent dip into their endowement, noticeable drop in attendance, and the highly controversial partnership with Saudi Arabia, the idea of American opera is in a state of flux. While this was defended by Gelb as an example of cultural exchange, the fact the country has opera can be interpreted as a method of smoke-in-mirrors, a distraction from the country’s numerable, indefensible, human rights violations.

Back home, across the continental US, opera houses and non-profit organizations are having to make the best of an extreme situation. In Detroit, the Trump administration’s cut to arts and humanities funding leaving cultural life in the city highly vulnerable to external threats. The devastating effects of Trump’s slash to NEA funding on the basis of eliminating “wokism” and the ostensible threat of “gender ideology,” going so far as to centralize his dominance over American culture through co-opting institutions like the Smithsonian and the Kennedy Center, is making the importance of non-federal programs that much more important.

Funding opportunities like the American Opera Initiative, OPERA America and their programs, along with local arts councils and their initatives, are helping opera in America keep going. These cuts, as Philip Kennecott wrote for The Washington Post, is not about concerns for the financial well being of America but the ideological dominance over others. As a result, “what remains of the endowments are being explicitly politicized…made to align not just with big, broad administration priorities, but to serve…personal demands of the president.” Trump has become an operatic antagonist, the Cantonese show, “Trump: The Twins President,” poking fun at the convicted felon.

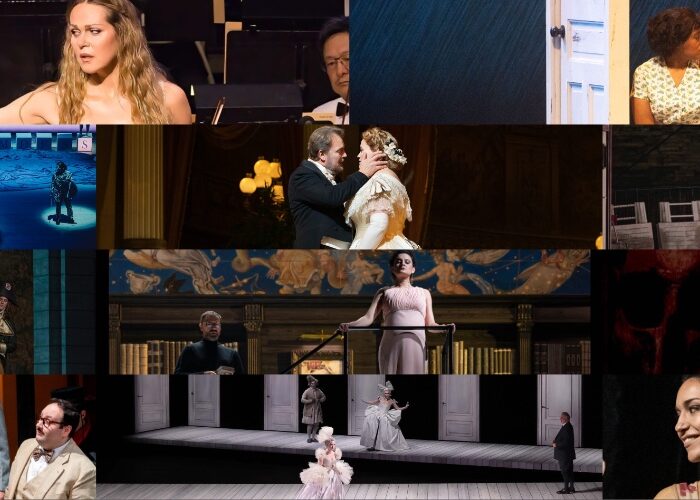

For the next three months, Opera Meets Film will be tackling the issue of America’s operatic cultural woes from a somewhat more positive angle, that is through the medium of documentary cinema, and what it can show us about the culture and those within it. This month, I wish to focus on a documentary currently in progress, Peter Rosen‘s “New American Opera” explores the contemporary American opera scene and the creation, rehearsal, and production of new works. Focusing on some of America’s leading opera composers and affiliated creatives, from Jake Heggie (“Dead Man Walking,” “Great Scott,” “It’s a Wonderful Life”), Kamala Sankaram (“A Rose,” “Formidable,” “Looking At You”), and producer Beth Morrison (Beth Morrison Projects), the documentary seeks to bring attention to the world of contemporary opera in America. However, the (in-process) documentary is not just about opera in America but the ways it has creolized the legacies of popular music in America as a whole,

New American Opera will explore influences from across the musical storytelling spectrum – opera, Broadway, alternative music-theater, etc.– that are contributing to the shift toward a new, uniquely American art form.

The documentary medium, as these next three months will show, is important as it demonstrates that while Trump’s America has rendered arts and humanities initatives vulnerable to external attacks, such work is by no means finished nor motivations atomized. Knowledge, legacies, and histories can continue for future audiences, but only if we do it together. While centralization occurs on one side, solidification of alternative networks of funding opportunities is occuring on the other, federal support no longer the only means for the sustainment of cultural life in America. The arguments for and against NEA funding are complex and multi-faceted. While one can argue either way, the idea that by eliminating the NEA, this would be “allowing artistic innovation to flourish without political interference or forced taxpayer subsidies,” is axiomatically idealistic, if not downright harmful.

A film about the development of new operatic works in America, with the express goal to increase ticket sales, an issue in its own right as 2023 statistics show (i.e., the higher the budget, the lower the ticket revenue was), getting audiences to experience contemporary opera is a task in its own right. The disagreements with new opera range in nuance and sophistication. However, Jenna Simeonov of Schmopera begs a good question, “Is it fair to say that people who go to the opera to hear beautiful music are missing a large part of the point?”

The role of the documentary opera film becomes a vital component here, and one whose role in contemporary opera works is increasing. Bringing to the fore the innumerable possibilities afforded to the contemporary composer, opera’s incorporation of the cinematic, the digital, and the virtual, allows opera to meet listeners at their level. But the documentary form allows even greater creator-audience interrelationality, taking a step away from the stage and into the preparatory realm behind the performance, performers, and spectacle of art itself. Many already exist, films like “Tenor,” “Viva Verdi,” “The Magic of Grace Bumbry,” and the documentary of Atlanta Opera’s 96-hour opera competition, providing unprecedented access into the world of opera past and present alike.

The discourse around the topic of the documentary’s true purpose and function centers around the notion that instead of cinema’s use of facts in a fictive way, as recent films like ‘“Maria” exemplifed, the documentary allows for the interrogation of real events and speaks to our desire to understand the world around us. Defined as epistemophilia (i.e., the obsession with knowledge), our yearning to know and discover new perspectives, outlooks, and orientations on the often overlooked details of life paints the documentary as a powerful mode of engaging with life. Coiner of the term documentary, Canadian filmmaker John Grierson, noted in his 1932 essay, “First Principles of Documentary,” that the documentary is an excellent method of showing life in all of its moving forms, that life provides the best material, and that cinema provides the best form to capture life and its complexities.

So too do I follow such line, that if one wishes to better know opera, while attending operatic performances does help to a degree, one can learn a great deal more through documentary exposure, where opera’s lesser-scene aspects can be experienced. The historical documentaries on opera available on YouTube are wonderful and a particularly benefital place to start, but it’s through documentaries dealing with the creation of works that we can learn about what it takes to not only contribute to but create artistic culture itself. With “New American Opera,” we’ll be able to step behind the curtain and experience what it takes to make contemporary opera in America.