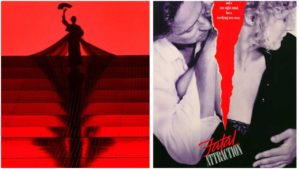

Opera Meets Film: The Narrative Parallels Between ‘Fatal Attraction’ & ‘Madama Butterfly’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features “Fatal Attraction.”

What do “Wall Street” and “Fatal Attraction” have in common, besides both starring Michael Douglas and New York City? They are both modern retellings of a classic opera. While “Wall Street” is “Rigoletto” through the lens of the corrupt business world, “Fatal Attraction” is what happens when “Madama Butterfly” gets turned upside down.

“Fatal Attraction” tells the story of Dan Gallagher, a married man with a daughter. He meets Alex Forest at a party and promptly has a weekend love affair with her. But when he tries to shake her off and move on with his life, he finds out that she’s pregnant with his child and refuses to be thrown away. The more he rejects her, the more aggressive she becomes, eventually entering his home and attempting to kill his wife.

The parallels between the Puccini opera and the Adrian Lyne thriller are actually quite potent. Dan is Pinkerton, a man who thinks he can have a good time and then pretend it never happened; when faced with Alex’s pregnancy, he simply tries to sweep it under the rug. He tells her that he’ll pay for the abortion and when she tells him that she’s having the baby, he questions why he can’t have any input in the decision. The film was released in 1987 and was clearly intended to relate to Dan’s point of view as much as possible. But over 30 years later, the complexities of the relationship actually allow for the audience to assimilate the perspective of Alex more readily.

She, of course, is the Cio-Cio San stand and the film actually makes this parallel very obvious with its use of two excerpts from the opera. The first time we hear a passage from “Butterfly” is in the midst of Dan and Alex’s weekend together. They’re enjoying lunch while listening to the opera. In fact, Dan notes that it’s his very favorite opera and even mentions that he saw it at the old Metropolitan Opera with his father. He goes so far as to note that he wasn’t ready for the opera’s ending when Butterfly ultimately kills herself. The music they are listening to is actually the very ending when Cio-Cio San prepares her suicide and sings one final time to her young child. As the scene draws to an end, the camera cuts to a close-up of Alex, the final dissonant chords ringing over her smiling visage. It’s a rather twisted and uncomfortable image to juxtapose with the music, but it does a few things. It hints at the danger that Alex will eventually become for Dan, but also aligns her with Cio-Cio San’s tragedy quite prominently. The rest of the scene is played out mostly in a wider two-shot, so the choice to punctuate the tragic scene with a specific closeup is meant as a very direct narrative and emotional device for the viewer. The fact that both characters are prominent parts of this scene only adds to the subtextual suggestion that their story is but another version of the one they are conversing about and listening to.

But the connection is strengthened later on when Alex realizes Dan wants nothing to do with her. In one of the most potent scenes of the film, Alex is shown sitting on the floor turning a lamp on and off as the camera moves toward her. Meanwhile, the scene cuts back and forth between Dan, his wife, and his friends, at the bowling alley having a blast. In the background, non-diegetically, we hear Butterfly’s yearning hope as she narrates to Suzuki about her hopes of seeing Pinkerton again. This entire scene, despite the back and forth editing between scenes, is told from Alex’s point of view. She’s immersed in Butterfly’s own longing.

But that’s where the narrative makes the shift. Both women hold on to the hope of being with their lover, but realize the impossibility of the situation because of his status as a married man. But where Cio-Cio San is mostly passive throughout Puccini’s opera, Alex is actually the most active character in the entire movie. Dan’s increasing rejection drives her more and more toward madness, spiraling down a tragic path that mirrors Cio-Cio San’s. Their respective fates are thus self-imposed in a way, even though the film suggests at Alex’s mental instability throughout.

What is worth noting is that while Alex is ultimately the antagonistic force in the overall narrative, the film does take pains to illuminate her perspective, much as the opera focuses on Cio-Cio San’s suffering. Alex isn’t simply an obsessive woman trying to have something that doesn’t belong to her. She’s a woman that feels abandoned and thrown aside and she’s speaking out against it. Ultimately, the damage done to the Gallagher’s isn’t the result of a crazy woman trying to ruin their existence, but the consequence of a man making selfish decisions for his own pleasure and then trying to act like it never happened. Like Pinkerton, Dan’s behavior causes suffering for those that love him the most.