Opera Meets Film: Kotlyarevsky’s ‘Natalka Poltavka’ From Stage to Screen

By John VandevertUkrainian writer Ivan Kotlyarevsky wrote the original story of “Natalka Poltavka” in 1819. Scholars and nationals alike consider Kotlyarevsky to be the “father” of Ukraine’s literature. Having helped Ukrainian literature make the jump from its older form to its new form in the late 18th to early 19th centuries, Kotlyarevsky (much like Pushkin for Russian literature) mirrored the societies in which he lived, often in masterfully satirical ways. Like most upper-class families, military service was de rigueur. After the military, Kotlyarevsky attended seminary from 1796 to 1808 before finding his way to the theater. He started his writing career in the late 1790s with his three-part poem “Aeneid,” credited with being the first piece of “New” Ukrainian literature written in the vernacular. Ukrainian literature’s transformation at the end of the 18th century took place within an equally transformative network of literary and linguistic developments.

From Page to Stage

In literature, emphasis on celebrating folk traditions and the cultural pride of the Ukrainian people, marked by satire and humor, helped fuel the growth of a nationalist sense of individuality obfuscated by the Russian empire. Additionally, the Enlightenment had spread across Europe, bringing with it the movements of Sentimentalism and Romanticism. In Ukraine, literature was the premiere spot for critiquing social injustices, “old” conceptions of morality (morals lie above social reality), and, most importantly, developing the national identity. Arguing the illegitimacy of the “Little Russian” title, the new Ukrainian literature advocated not only for the preservation, but for the celebration of the Ukrainian worldview and way of life. Kotlyarevsky depicted Ukrainian existence at the time, and the poem quickly grew in popularity as a nationalist embodiment of Ukrainian life. The play became the basis for Ukrainian operas such as “Aeneas on a Journey” by Y. Lapotynsky and “Aeneid” by M. Lysenko. In 1816 Kotlyarevsky became the director of the Poltava Free Theatre, Ukraine’s first professional theatrical group. Many great playwrights wrote for the theatre, including Russian writers Denis Fonvizin and Vladislav Ozerov and operatic composers such as Stepan Davydov and Cavos Katarino. In 1819, Kotlyarevsky wrote the play “Natalka Poltavka” and vaudeville “Moskal the Magician” and, just like “Aeneid,” the plays instigated the serious development of Ukrainian dramatic literature.

The first musical adaptation of Kotlyarevsky’s play began around the early 1830s with Ukrainian composers like Anatoly Barsystsky, who, in 1833, published a series of songs corresponding to their play alternatives (the original sheet music is quite something). Other nationalist composers like Alois Jedliczka and Russian composer Sergei Vasilyev would make their own versions, but in 1889 the most well-known setting premiered.

Born in the Poltava region of Ukraine in 1842 to a highly educated and affluent family, Mykola Lysenko is a legendary figure in Ukraine’s musical history as a voracious folk-music ethnographer, pedagogue, and, most prominently, a people’s scholar and artist. Having begun his musical training as early as five, composing his first piece at age nine (“Polka”), at 14, he had become extremely entranced by the Ukrainian folk culture thanks to the poems of Taras Shevchenko. Lysenko’s ethnographic passion, however, would fully blossom during his time at Kharkiv University. Kotlyarevsky formally studied the natural sciences yet informally participated in Ukrainian student folk choirs. He began his musical ethnography, mastered Ukrainian, and earned a place within the “Old Community,” a 19th-century circle of Ukrainian intellectuals focused on developing a national cultural identity. During his final year of studies, he had begun work on his first opera, “Natalka Poltavka,” yet halted due to inexperience. However, by 1889, the year “Natalka” premiered, he had five operatic works under his belt.

Nevertheless, after a brief time at the Leipzig Conservatory and a sizeable expansion of his ethnographic work, in the early 1870s, he convened with members of “The Mighty Handful,” where he learned how to synthesize his nationalist folk research with Europeanized compositional structures and methods. However, during this time, he faced censure because of his unapologetically Ukrainian compositions and sympathies. Later, in 1880 the ban was lifted, and Lysenko set about working on various projects, including the opera, “Taras Bulba,” a 10-year project never performed during his lifetime, although Tchaikovsky would offer a Russian-language staging in St. Petersburg of which Lysenko starkly denied. As a highly eminent, nationalist-oriented, and well-traveled ethnographer, his worldly approach towards the valorizing folk culture itself brought him into contact with not only Ukrainian culture but Serbian, Czech, and even Polish as well.

During the 1880s, he was busily expanding Ukraine’s amateur choir culture, authoring scientific texts on Ukrainian folk culture, and, most importantly, in 1885, composed one of the most recognizable pieces of Ukrainian music culture to date, “Prayer for Ukraine.” Finally, after completing two more operas in 1889, Lysenko published the comic opera “Natalka Poltavka,” although, by his own account, he only wrote the piano parts. In truth, he turned melodies into arias, duets, and choruses and created orchestral accompaniments while also including monologues and spoken text. The opera premiered in Odessa on December 24th and featured Igor Stravinsky’s father, Fyodor, in the role of Mykola. In 1925, the opera entered the Kyiv Opera Theatre repertoire and was most recently used as the headliner for the house’s 2022 season prior to the start of the Russo-Ukrainian war.

From Stage to Screen

In the 1930s, the world was a very turbulent place. In Germany, the political influence of the Nazi Party was rising, while in America, the Great Depression had just begun. In Soviet Russia, the first and second “Five-Year Plan” (a strategy for economic development), as well as the “Socialism in One Country” state policy, were enacted, while from 1932 to 33, the Ukrainian “Holodomor” (artificially designed famine) would ravage the country’s population. On top of this, in 1936, the Olympics would be held in Berlin, an event saturated with antisemitism and global participants’ empty threats of boycotting the games. The infamous phrase, “politics has no place in sports,” was coined by the then US Olympics Committee president Avery Brundage during this period. This is all to say that the Ukrainian director Ivan Kavaleridze brought an overtly pro-Ukrainian film into a world that was anything but calm.

Ukraine’s cinematic culture, at least in the country’s Western part, annexed by the USSR in 1939, was robust in scope, with Lviv being its main hub. However, filmmaking in Ukraine’s central region was mostly dominated by the company “Ukraine-Films” (of the Dovzhenko Film Studios) based in Kyiv. Starting as early as the 1920s, Stalin’s policy of “Ukrainization” sought to bolster Ukraine’s national consciousness to foster increased participation in the Bolshevik project. While elements of Ukrainian culture were championed, it was only under strict pretense, as the “Red Renaissance” showed. In 1930, the Soviet government consolidated cultural institutions for propagandistic use, and the censorship of cinematic art began in earnest. Stalin’s aesthetic policy of “Socialist Realism,” formalized in 1932, also contributed to the alienation of the film industry. As a result, the studios had to create brazenly political works whose aesthetics couldn’t align with the specter of formalism. Yet, the 30s marked a period of technological expansion, most notably the creation of color films and the mastery of sound accompaniments.

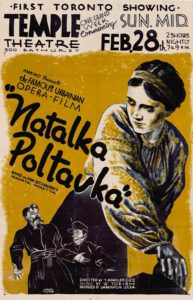

In the 1930s, Ukrainian director Ivan Kavaleridze had earned himself a reputation for dissidence as some of his recent films pushed the aesthetic line at the time. Prior to “Natalka Poltavka” in 1936,he released the film “Prometheus,” that same year, receiving pushback from Soviet critics. He soon released “Natalka,” shot by Ukraine Films, the first operatic-themed opera in Ukrainian film history. Using an actor/singer structure (i.e., lip-syncing), the film would receive its US premiere in February 1937, yet a year earlier, in December, another version premiered. Shot by Edgar Ulmer, with assistance from Ukrainian choreographer and “father” of Ukrainian folk dance Vasyl Avramenko, the version was partly an attempt to earn much-needed money but also to counter the Sovietized nature of Ukrainian cinema and raise awareness of the Ukrainian identity. To do this, in 1934, Avramenko created “Avramenko Film Production.” After having met Ulmer, who gained popularity in Hollywood for his interest in ethno-nationalist themes, filming began.

Apparently, Ulmer and Avramenko’s version received wonderful feedback. As soon as they released it, the film made its rounds in America, going from the East coast to the Pacific Northwest, before eventually making its way to Canada. However, even though its publicity had earned the film considerable capital and attention, critics were quick to point out its structural flaws and its producer’s inadequate training. Quickly as it came, the film fell from public radar as Kavaleridze’s film made its American tour thanks to Amkino Corporation (1926-1970), the official distributor of Soviet films for the United States marketplace. Kavaleridze’s film’s American popularity was an intense three-week period, during which it was screened at the Roosevelt Cinema in New York—an underappreciated piece of cinematic history. (The theater was known in its history for Yiddish burlesque before undergoing a name change.) In 1941, the venue was split into two theaters, with one being destroyed and replaced with a parking lot. According to journalists at the time, the film did its duty and entertained. In 1969, Dovzhenko Film Studios updated the film, and in 1978 the movie was again remade. This time, Ukrainian director Rodion Yukhymenko directed the film, which starred some of Ukraine’s leading stars, including Nataliya Sumska, Fedir Panasenko, and Les Serdyuk. Featuring color and sound, the film is certainly a joyful rendition.

What “Natalka Poltavka” Means

But what does the story of “Natalka Poltavka” mean, and why is it important to the cultural identity of Ukraine? It begs repetition that Kotlyarevsky wrote the story in order to boost the repertoire at the Poltava theatre where he worked. However, some point out that it was also written in nationalist retaliation towards Ukrainian playwright Oleksandr Shakhovsky’s unfaithful depiction of the Ukrainian people. When Ukrainian self-consciousness was a highly sensitive issue, any depiction seen as mis-representational was inexcusable. How was it that Kotlyarevsky’s play was so relevant it became a calling card of the Ukrainian cultural identity itself? Generally, the play depicts the Ukrainian people as not as culturally bequeathed to Russian influence nor victims of circumstance and anomic along identity lines. Rather, Kotlyarevsky depicts the Ukrainian people as tenacious, moral, troubled but good-hearted, kind, selfless, and religiously devoted, not skewed by Orthodox teachings but by the spiritual core of what it means to be believers in God. He showcases the dignified nobility that was peasant existence, not shying away from the hardships that such an existence brought.

Kotlyarevsky also pulled from Ukrainian folk culture’s rich pool of ritual practices, traditions, and music, using folk songs to underscore the character’s temperament and symbolism. Songs like “You can see the ways of Poltava” and “Oh, I’m a Natalka girl” are paradigmatic of Ukraine’s authentic musical soundscape. The story itself, however, subverted the conventional “old” literary notion of internal morality, suggesting that the social construction of one’s environment had as much to do with one’s moral code as one’s internal temperament. In this, Kotlyarevsky critiques the Imperial system and serfdom for pushing the peasantry to the brink of destruction and forcing them into morally questionable circumstances. Kotlyarevsky also re-conceptualized happiness as a construct, suggesting that its creation is as much dependent upon external influences as internal, making Kotlyarevsky’s anti-imperialism sympathies clear. Further, each character was also a symbol of some element of Ukraine’s national spirit. Natalka and her mother, Terpelikha, were sincere, poor but selfless, chaste, opportunistic, and deeply principled individuals, showcasing the refined identity of Ukrainian women. Peter, Natalka’s lover, is quiet and submissive, yet highly moral—qualities of the righteous Christian believer. Mykola is an example of the happy helper, using his internal joy as a mediator between conflicting parties, while the Coachmen represent the morally good yet externally hostile, believing in love and affection yet unhappy in one’s life.

Thanks go to Pavlo Artymyshyn for his recent article on the 1936 film by Ulmer and Avramenko. Read it here.

Watch the 1978 Film