Opera Meets Film: How Werner Herzog’s ‘Fitzcarraldo’ Frames Its Conflict With Enrico Caruso, Verdi & Bellini

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Werner Herzog’s “Fitzcarraldo.”

A man on a mission to build an opera house in the middle of a hostile jungle. This is a statement that can apply to anything relating to art, the modern world often hostile to the advancement of the arts, despite their importance to our social development.

Director Werner Herzog literalizes this struggle in his famous “Fitzcarraldo,” a film that actually took Herzog to the extremes of his art. For those unaware (massive plot spoilers ahead), the climax sees the characters try to push a massive 320-ton steamboat over a hill. Instead of using practical effects to achieve the cinematic effect, Herzog decided to do it for real, calling himself the “Conquistador of the Useless.”

It is ultimately rather fitting for how the entire film plays out with the hero Fitzcarraldo ultimately failing in his goal and being forced to settle for a makeshift opera house.

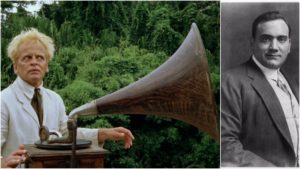

Opera plays throughout the film, most prominently with a few recordings by Enrico Caruso that Fitzcarraldo shows to the natives of the region. These moments express precisely why the hero is so intent on building his opera house – he sees it as a means of connecting with others, despite the fact that the words of the music are foreign to the indigenous people. In one glorious moment, he gets natives, who seem primed to attack, to calm down and listen. While we never see the natives, we feel the palpable connection between them, the music and Fitzcarraldo.

A Staged Failure

These moments of connection are flanked by formal performances of opera, one in a traditional theater, and another on the steamboat at the film’s climax. The first performance is supposed to feature Enrico Caruso in the final trio of Verdi’s “Ernani,” a piece well-conceived for the film’s overlying theme. In that trio, Ernani and his beloved Elvira try to convince the evil Silva to withdraw his claim on Ernani’s life. Of course, Ernani himself made an unbreakable oath to kill himself when Silva sounded his own horn. But Ernani’s pleas are useless, his own self-inflicted pain inevitable. This mirrors Fitzcarraldo’s own fate, his decision to become a conqueror of the useless, a goal he set without any pressure from anyone else. His suffering was his choice. Moreover, as Ernani is making Elvira suffer, Fitzcarraldo’s selfish mission also causes issues for his beloved Molly, who he leaves behind on his voyage.

From this passage alone, we know that he is doomed to fail in his mission.

The Polar Opposite

But the solution he ultimately comes to at the climax of the film subverts this all as the steamboat returns with a makeshift production of “I Puritani,” the glorious “A te o cara” being sung rather prominently. Instead of the tragedy left from Verdi’s staging at the start, the choice of one of Bellini’s most gorgeous melodies leaves the film on an uplifting note. Moreover, the aria starts off as a solo passage before transitioning into a massive ensemble that features soloists and chorus. The trio in “Ernani” was one of individuals in pain, but the Puritani passage explores an entire community in rapture. While Fitzcarraldo does not get the success he longs for, he gets this one beautiful moment of catharsis, as does everyone involved.