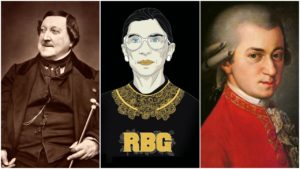

Opera Meets Film: How ‘RBG’ Employs Music From Rossini, Mozart, & Others Operas to Explore the Supreme Court Justice as an Icon

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will hone in on a selection or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perceptions of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features opera in the documentary “RBG.”

“When I am at an opera, I get totally carried away. I don’t think about the case that is coming next week, or the brief that I’m in the middle of. I am overwhelmed by the beauty of the music, the drama and the sound of the human voice, it’s is like an electric current going through me. Justice and mercy, they’re all in opera. Very grand emotions.”

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg is quite possibly the most famous and beloved opera fan in the entire world. Her passion for the art-form is well-documented and it isn’t rare to see her appearances at a performance here and there (personally, I was able to witness her presence at a recent Richard Tucker gala where she drew more applause than arguably any of the singers on stage that evening).

So it’s no surprise that documentary about her life and career would feature some well-placed operatic excerpts helping in the telling of her story. The film literally stops all of its momentum to make this point, showing the Supreme Court Justice attending the Santa Fe Opera’s 2017 production of “Lucia di Lammermoor” starring Mario Chang and Brenda Rae (the above quote comes during this section). Throughout the film, opera is used as a transitional tool to move from one moment in her life to another. Some are rather indicative of tone and transition, such as the dark chords that presaged the mad scene in “Lucia di Lammermoor” as the documentary shifts focus to the Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld case.

But then there are a couple of well-placed excerpts that really highlight the documentary’s playful nature and Bader Ginsburg’s own affability as a person.

The first of these comes right at the start of the film where we hear Rossini’s iconic “Il Barbiere di Siviglia” overture kick off the opening titles. The images of Washington D.C. shine over the vibrant Rossini music, giving a sense of sunshine and positivity. But then filmmakers Julie Cohen and Betsy West throw some nice counterpoint into the mix by means of men making some choice comments about Bader Ginsburg. “This witch. This evil doer. This monster,” says Michael Savage. “An absolute disgrace to the Supreme Court,” says a President whose very words are likely a more apt description of himself. “She’s anti-American.” “She’s a zombie.” All of these insults are thrust over this montage and yet, they have no impact.

Why? The sunshine of Rossini’s music coupled with the bright day portrayed in the images, makes those comments laughable. The music’s associations with comedy here extend to showing the transient nature of these comments as the film eventually settles on one final image – the Supreme Court itself. It’s a subtle political commentary told through a communion of imagery and music counterpointing dialogue. It also lets us know immediately what we’re in for – a demonstration that all of these opinions will be subverted, contradicted, and ultimately thrown aside throughout the remainder of the film. By the end of the picture, Ruth Bader Ginsburg will not be seen as “a witch,” or “a disgrace to the Supreme Court,” but a hero.

Later in the film, we cut to a montage of Ginsburg exercising. The segment emphasizes the Judge’s continued vitality into her 80s. One of her friends notes that while Bader Ginsburg can do 20 pushups three times a week, they can’t even find their way to floor. To emphasize this virtuosity, the directors employ a soundtrack featuring “Die Hölle Rache” from Mozart’s “Die Zauberflöte.” Again, like the Rossini, this is a renowned piece of music and most people that hear it recognize where it’s going – the series of high arpeggiations up to several high F’s, a feat for any singer. The connection here is less subtle than the film’s opening montage but no less effective. Ruth Bader Ginsburg is every bit the “Super Diva” the shirt she wears throughout purports.

The second example also builds on the film’s ultimate aim of not only establish Ginsburg as a remarkable human, but also exploring her myth and legendary status. It’s right there in the title itself. The opera and classical music excerpts, which really make up the most memorable musical moments in the film, are hundreds of years old. Their impact has reverberated through the ages. They are timeless. Through this communion of music and story, the film is also making a strong argument that its subject, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her life’s work not only transcends time, but will continue to do so for years after she’s gone (admittedly, it certainly helps that the Chief Justice is so passionate about the art form).

Categories

Opera Meets Film