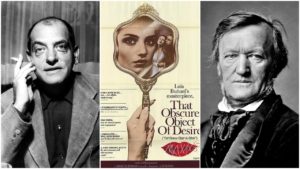

Opera Meets Film: How Luis Buñuel Comes Full Circle With Wagner in ‘Cet Obscur Object du Désir’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Luis Buñuel’s final film “Cet Obscur Objet du Désir.”

Luis Buñuel’s “Cet Obscur Objet du Désir” ends with an explosion.

Given the context of the film and its creator, the literal flames that cover the frame have a metaphorical purpose in a film in which the passions of the two central figures Mathieu and Conchita are full of instability, but endless desire. In the backdrop of this back-and-forth “love” story, is a series of terrorist attacks by extreme leftist groups.

The film tracks the duo’s relationship coming together before inevitably falling apart, with both pursuing one another and yet, as Conchita makes note, not really wanting each other as they are. Faced with Mathieu’s unquenchable lust for her, Conchita notes that if she were to give him her virginity, he would no longer want to be with her. Mathieu, meanwhile, professes to simply wanting to “possess” her. There’s also the fact that both characters are portrayed by two different people (Conchita by two actresses, Ángela Molina and Carole Bouquet, while Mathieu performed by Fernando Rey and voiced by Michel Piccoli), which furthers this notion that neither could ever have the other fully.

For over an hour and 45 minutes, we are treated to this non-stop back and forth between the two, with no end in sight. Even when after Mathieu violently assaults Conchita before making his way to a train station leaving for Paris, Conchita finds herself following him onto the train.

So it is that in the film’s final scene, the two are back in a blissful state, likely headed toward a restart of the same pattern.

They head to a shopping center where we hear an announcement. The duo then looks into a window to observe a woman working on what appear to be bloody white linens she has removed from a mysterious straw sack that has followed our protagonists throughout the film.

Suddenly over the loudspeakers, we hear a voice stating, “Now let us have music.”

Suddenly, we hear the love duet between Siegmund and Sieglinde from Wagner’s “Die Walküre,” precisely at the moment when Siegmund utters “Ein Minnetraum gemahnt auch mich: in heißem Sehnen sah ich dich schon! (A love-dream wakes in me the thought:

in fiery longing cam’st thou to me).” The symbolism of the text in this setting couldn’t be clearer if Buñuel tried.

Siegmund and Sieglinde’s forbidden love, briefly previewed in this final scene thus provides a perfect companion to Conchita and Mathieu’s. While theirs is not an incestuous one in the way that Siegmund and Sieglinde’s is, it is never intended to be fulfilled. Like the Valsung siblings, the moments of joy will continue to be brief, overtaken by immediate grief and suffering, something we witness throughout the film.

And just as Wagner’s music surges forward – the Explosion! And the film comes to a close.

It’s an apt metaphor without any doubt. Mathieu and Conchita’s back and forth had nowhere else to go but to an inevitable self-destruction for both. Death was the only thing that would save them from this cycle.

Of course, Death is what saves many of Wagner’s characters from their continued unfulfilled desires and endless suffering in the “real world.” “Tristan und Isolde” obviously provides the major template there, but so does “Die Fliegende Holländer.” Death also proves a cure in the Ring Cycle where the evil of the old order can only be eradicated by flames so a rebuilding of a new one from the ashes can take place.

Finally, one cannot overlook the fact that Buñuel returns to Wagner throughout his oeuvre, starting with his first film “Un Chien Andalou” and continuing with “L’Age d’Or” as well as numerous references in other films including “The Exterminating Angel” and “The Phantom of Liberty.” The link between “Un Chien Andalou,” his first film, and “Cet Obscur Object” is particularly striking.

In that earlier film, Buñuel turns to Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde” in moments presaging death. A bicyclist falls over and we hear “Tristan.” A young man is shot and we hear “Tristan.” In portraying Wagner as a preview of incoming death in his final film, he has come full circle, connecting the start of his career with its very last frame.

Categories

Opera Meets Film