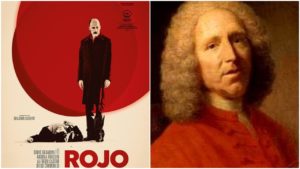

Opera Meets Film: How ‘Les Indes Galantes’ Highlights The Emotional Turbulence of 1970s Argentina in ‘Rojo’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Benjamín Naishtat’s “Rojo.”

“Rojo” is a unique cinematic study in structure. While it does have a major plot thread and central character that dominates the film’s overall story, it in fact operates on a far larger scale in which the central character is the world of Argentina in the 1970s before the military coup that would change the country’s destiny in the years thereafter.

As such, the film winds up tracking a series of different narratives of differing focus and length, all unified under themes of male corruption, violence, and the disappearance of the innocents. The film opens with a house raided by a number of people, symbolic of the country being destroyed from within and pilfered by anyone who sees the opportunity to do so.

From there, we track the story of Claudio, the town’s upstanding lawyer as he murders a man and then hides the crime. While Claudio has to deal with the repercussions of this crime, he also helps a friend make a backdoor deal on the abandoned house while his daughter’s jealous boyfriend acts out on his own violent potential.

In addition to the colliding plot threads, the story also features a wide range of stylistic choices and tones, emphasizing the emotional instability of the period.

Among those choices is the inclusion of some music from Rameau’s famed “Les Indes Galantes.” We experience the famed baroque music during scenes in which Claudio’s daughter engages in her dance class, with her performance eventually closing out the film itself.

The music operates on many levels. “Les Indes Galantes” itself is a mixed genre work, combining opera and ballet in equal measure. What’s more, unlike most operas, it doesn’t feature one main plot for its four acts, instead following four separate arcs across four different exotic locations, including The Ottoman Empire, Peru, Persia, and North America). As such it operates both as a direct correlation to “Rojo” but also its antithesis, allowing Naishtat to draft a textual conversation between the two works. Structurally, “Les Indes Galantes” is similarly untraditional as “Rojo” in both of their respective art forms. But conversely, the French opera focuses on the expansiveness of its themes by showcasing it across numerous worlds while “Rojo” is all about expressing the insular qualities of its theme by placing it in one specific time and place of great historical importance.

The themes are also of great value as they are at odds. “Les Indes Galantes” is unified by the themes of love with each of the acts ending happily for the central couples in the work. As such, the opera-ballet is a profession of love and its power to overcome all challenges such as race, social stature, and culture, among other aspects.

But “Rojo” centers on death, disappearance, loss of identity, and jealousy, among other negative emotions and aspects. Men are at the core of the story and they are mainly hurting their natives, much as the incoming coup will harm the identity of an entire country for years to come. Where “Les Indes Galantes” celebrates humanity’s ability to come together, “Rojo’s” focus is on how we destroy those around us.

Finally, it is essential to take one last look at how “Les Indes Galantes” is brought into the conversation regarding “Rojo” – Paula. While everyone around the world of the story, including her own father, is destroying and damaging, she is creating. She is the lead dancer of the performance and is depicted as an inspirational force to others around her.

Emotionally, her scenes provide the audience with an escape from the general emotional turmoil and violence, giving hope of something pure emerging from the destruction. The fact that the film ends with her performance points toward the eventual phoenix that would rise from the turbulent years ahead. We sense this and feel this in the contradictory emotions that arise from hearing Rameau’s joyous music alongside the final images of the hypocritical Claudio looking on at the performance, facing no repercussions for the crime he committed.

Ultimately, the film remains hopeful despite the full knowledge of the pain that must come first.