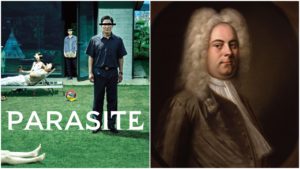

Opera Meets Film: How Joon-Ho Bong’s ‘Parasite’ Develops Ironic Narrative Through Handel’s ‘Rodelinda’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Joon-Ho Bong’s “Parasite.”

In reviewing “Parasite,” Indiewire’s David Ehrlich has previously stated that director Joon-Ho Bong is a genre unto himself. This very film starts off as a comedy of sorts as it follows a family of four slowly con themselves into jobs with a wealthier family. But then the film takes a turn into a darker drama that eventually borrows from the horror genre as it delves into the harsher realities of the story’s themes.

This interplay between a wide range of cinematic genres is matched only by opera, specifically that of the baroque variety. Its music might be full of sprightly bounce or soaring lament with its stories of mythical heroes only topped by the camp of their visual productions. Baroque more than any other opera genre matches Bong’s own cinematic style.

So it is no surprise that throughout his film, audiences are greeted with the splendor of baroque music by the likes of Handel at crucial juncture of the narrative.

But there are two particular passages that really resonate for their use of two arias from “Rodelinda.”

The first of these happens right when Kim Ki-taek, the patriarch of the family lands a job as a driver and as the family prepares to get rid of the housekeeper so that they can bring their mother into the fold to complete the quartet. Over an extensive montage, we hear “Spietati io vi giurai.”

In this aria, Rodelinda swears against the cruel men that want to do her harm. The music is full of agitation, explored by Rodelinda’s coloratura runs and the music’s own sense of drive. But in the context of the film, the aria’s bouncier nature comes through almost adding an innocent comedy to the family’s master plan and execution.

On the surface, this creates an effect that lightens the dark behaviors of the family in the audience’s eyes. Classical music of this nature creates relaxation for the audience and combined with the montage, we remain on the Kim family’s side.

But the music is a Greek chorus in this film, commenting on the events in unexpected ways. This is one such instance. Rodelinda’s angry cries of vengeance is a condemnation of the family’s behaviors for this is the first time that they obtain their positions not just by lying, but by methodically forcing their predecessors out of their positions. They have gone from con-men to evildoers, as fun as it might seem. This moral ambiguity is being called out by Rodelinda in her aria, even if the film audience doesn’t register it right away. It is also a warning for what is to come later.

The family is eventually found out by the housekeeper that they force out; she has been hiding her husband in the basement of the house for many years. After she gets killed by the family, he has his revenge during a major party scene.

And this is when we come to our second “Rodelinda” aria, “Mio caro bene.” Expressed diegetically by a singer at the party, this aria is one of adoration and joy, a major contrast to the earlier aria.

But this is where Bong’s genius really works. This scene, with an aria full of love and joy, expresses a scene in which the Kim family will be destroyed with one of its members killed. Rodelinda sings of “No ho più affanni e pene,” but the reality is that grief and pain is about to consume the family. Again, this contrast creates a mixed perception and tension for the viewer, accentuating the moral ambiguity at the core of this story. Our heroes commit despicable actions of usurpation in the context of an equally problematic world in which those on top seemingly don’t deserve those advantages due to their own sheer ignorance.

There is one more essential layer in the choice of “Rodelinda” for the film – like “Parasite,” the opera deals with the consequences of usurpation. In this case, Grimoaldo steals the throne from Bertarido, who must recover his throne and wife and child. Eventually, he wins it all back with the Grimoaldo forced to step down. The opera ends with status quo restored.

One might see this as a mere coincidence but the decision to use two, and only two, arias from this opera cannot be overlooked. Nor can the fact that “Parasite” also ends with status quo restored, but with a tragic bent. The Kim family members do not lose their positions of power like Grimoaldo, but have lost a member and are separated from the other. The house that they usurped is taken over by another rich family with another person from the lower class smuggled into its basement. Finally, the Park family must once again deal with the trauma of its youngest member.

But in Rodelinda everyone gets a happy ending. In this context, Bong is indirectly commenting on the opera’s aim at a fairy tale ending. In his films, happy endings don’t exist, especially for the characters that cross the line. “Parasite” is no different.