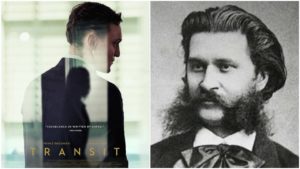

Opera Meets Film: How ‘Die Fledermaus’ Casts An Illusion Consciously & Subconsciously In Christian Petzold’s ‘Transit’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment will take a look at Christian Petzold’s “Transit.”

“Transit” is all about lost souls finding brief respite from the world’s hostile nature with one another. Throughout its running time, Christian Petzold’s thriller follows Georg, a refugee seeking solace from an incoming facist threat. He eventually settles on Marseille, under the guise of a dead author, he prepares what will inevitably be his escape to America.

During his time in Marseille, Georg finds companionship in a young boy Driss, who he spends time with in youthful activities such as playing soccer or going to a park.

It is during one of these scenes with Driss that we hear a brief excerpt from Strauss’ “Die Fledermaus,” specifically the waltz from the operetta’s overture, a complex emotional moment for the viewer.

Not all viewers will be conscious of the piece’s original context and Petzold might not actually care whether they do or not, but it still holds symbolic relevance. The waltz first appears during the overture, but then returns during the big party in which brings together a bunch of strangers who later profess their brotherhood toward one another. The film itself operates on a similar level with the refugees all congregating in Marseille, a purgatory of sorts, to provide comfort for one another.

We see it in Driss and Georg’s relationship or how he later helps Marie and Richard escape. We see it in the constant returns to the same restaurant where other similar refugees are bunched together. But like in “Fledermaus,” this moment is not meant to last, this brotherhood just circumstantial.

And so it is with the film’s emotional content, but in a different manner.

On a audiovisual level, the appearance of the “Die Fledermaus” excerpt’s upbeat and vibrant nature is a reflection of the scene taking place before our eyes. It bubbles with vitality like Driss’ smile as he interacts with Georg in the park.

But it so much more than just “Mickey Mousing,” or having a musical excerpt describe the emotion of a scene. It actually counters it too and works on a subconscious level for the viewer, informing him of the director’s own intentions with this relationship in the process.

The film’s score is composed by Stefan Will and its style is far more minimalistic and less melodic in nature; if anything, it is urgent and oppressive with its yearning. It is definitely not a Viennese waltz.

So the sudden appearance of this Straussian melody perks up the listener; it’s a fish out of the sonic landscape that has been created to this point. The few excerpts littered throughout the film offer similar counterpoint, but none more so than this grainy excerpt from a bygone era of dance and luxury in a far-off land.

And it is because the “du und du” feels out of place that the audience, whether consciously or subconsciously understands what Petzold is doing with the characters in this moment. They are meant to enjoy this moment, but like the waltz of a long-lost era, it is not meant to last. This moment is transitory.

Check out the trailer for the film.