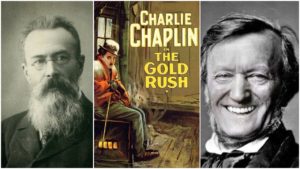

Opera Meets Film: How Chaplin’s ‘The Gold Rush’ Uses Wagner / Rimsky-Korsakov Quotes to Create his Most Operatic Film Score

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Charles Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush.”

“I had never seen grand opera, only excerpts of it in vaudeville – and I loathed it. But now I was in the humor for it. I bought a ticket and sat in the second circle. The opera was in German and I did not understand a word of it, nor did I know the story. But when the dead Queen was carried on to the music of the Pilgrims’ chorus, I wept bitterly.”

So said iconic film director and star Charles Chaplin upon seeing Wagner’s “Tannhäuser” at the Metropolitan Opera for the very first time.

The influence of Wagner’s music is felt in all of Chaplin’s films with some, especially “The Great Dictator,” rather openly utilizing the Bayreuth master’s music for the filmmaker’s means.

But perhaps no score is more indebted to Wagner’s genius than that of “The Gold Rush,” Chaplin’s most iconic piece and one that also borrows rather liberally not only from Wagner, but also from many works of Western classical music.

The 1925 film’s music is heavily reliant on the leitmotif, a fixture of Wagner’s operatic structure, and one that would go on to play a predominant role not only in most of Chaplin’s own scores but all Hollywood scores for years to come.

The most obvious use of leitmotif is every interaction between Georgia (played by Georgia Hade) and the Tramp (Chaplin). Chaplin utilizes a love theme that comes again and again as the two characters come together or when the Tramp ponders his love interest alone in his cabin.

Chaplin brings in “The Flight of the Bumblebee” from Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera “The Tale of the Tsar Saltan” for two bookended actions sequences in his film. Early on, the Tramp and Big Jim McKay arrive at Black Larsen’s cabin. As Larsen attempts to rid himself of the Tramp, the iconic piece dominates the soundtrack, the scurrying chromatic notes seemingly in synch with Chaplin’s fierce running in place as he tries to overcome the blowing wind from the door. In a subsequent shot, the piece’s propulsive fury adds to McKay’s own whirlwind entrance into the house. The piece’s inclusion drives the energy of the brief sequence, which while built on 12 shots carefully stitched together over a little over 30 seconds. If you rewatch the sequence without the music, some of the gags still work (especially McKay flying out the door the moment he enters), but some of the charm and energy is lost. This is a prominent display of how music is so crucial to the experience of silent film. Moreover, given the piece’s prominence, there is no doubt that audience recognition of the music will add to the experience through the cognitive consonance or dissonance that it might create.

Later in the film, the piece comes back when McKay and the Tramp fight to save their lives as the cabin lies on a precipice. Given the visible stakes of the scene, one could argue that music’s effect is slightly less reliant on the music for its dramatic effect. Instead, the importance of this specific piece being used in this context actually underlines the power of the leitmotif. We are suddenly reminded of that earlier scene where these two characters connected and forged their friendship. They overcame starvation together and now, in this climactic moment, they will not only overcome another sure death, but will become millionaires.

This is arguably Chaplin’s most clever use of leitmotif in the film, but there are a few other examples worth pointing out, if only anecdotally.

Remember that earlier quote about “Tannhauser” from Chaplin? Well, the opera’s famed “Song to the Evening Star” must have also impacted him because he explicitly quotes it as a leitmotif in “The Gold Rush.” Here’s a translation of the aria.

“Like a premonition of death, darkness covers the land,

and envelops the valley in its sombre shroud;

the soul that longs for the highest grounds,

is fearful of the darkness before it takes flight.

There you are, oh loveliest star,

your soft light you send into the distance;

your beam pierces the gloomy shroud

and you show the way out of the valley.

Oh, my gracious evening star,

I always greet you like happily:

with my heart that she never betrayed

take to her as she drifts past you,

when she soars from this earthly vale,

to transform into blessed angel!”

Wolfram’s aria yearns for hope and Chaplin uses it to similar effect in scenes where McKay and the Tramp are locked away in the cabin longing for food to overcome their starvation. Initial quotations of the aria are brief, but with each successive reprisal, Chaplin expands on the melody, creating a greater sense of longing as the melody is allowed to develop.

Finally, Chaplin quotes Siegfried’s motif from the Ring Cycle in association with the gold. The motif is not as obvious as that of “Tannhäuser” because Chaplin resolves the first phrase on a third leap instead of Wagner’s leap by a sixth (C natural to A flat), but discerning Wagnerians will immediately identify the piece when Chaplin repeatedly uses it in association with the gold. It’s very first appearance comes right after in the overture as Chaplin describes the challenges of the prospectors in Alaska. Slower iterations crop up when McKay finds the gold a few scenes later and at the climax of the film (it dovetails nicely with “The Flight of the Bumblebee”).

The score utilizes other quotations by Tchaikovsky and Elgar, creating what is arguably the most operatic score of Chaplin’s career.

Back in 1925, a score like this one emphasized the importance of music in silent film, a lesson that would continue to influence cinema thereafter.

Watch this enduring classic below:

Categories

Opera Meets Film