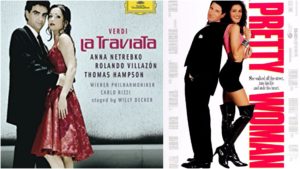

Opera Meets Film: How A Comparison of ‘Pretty Woman’ & ‘La Traviata’ Emphasizes Social Progress (& Lack Thereof)

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features the Richard Gere and Julia Roberts film “Pretty Woman.”

Verdi’s “La Traviata” is one of the greatest operas for a number of reasons. Music aside, its ability to make audiences empathize with a courtesan and weep over her failings is something that we now might take a bit for granted. And yet in its time, Verdi was going against social norms and challenging them. Simply put, courtesans were not women to look up to and by asking audiences to do just that, Verdi was destroying an age-old taboo.

And while society has advanced since, modern-day prostitutes, of all varieties, are still not seen as a social good. That taboo still stands strong, to the point that in many countries prostitution is illegal.

“Pretty Woman” is an interesting film in this context. A loose adaptation of Verdi’s opera, this film aligns itself with Verdi’s own destruction of social stigma, advocating for a desecration of social segregation and yet playing into it in its structure and character choices.

Changing Characters

Starring Julia Roberts as the hooker Vivian Ward, director Garry Marshall makes it clear from the way that he dresses her that she is among the lowest class of prostitute. Unlike Verdi’s courtesan, Vivian has no money and is desperate for whatever she can get. Whereas Violetta throws lavish parties and entertains Counts, Vivian works the streets until she happens upon Edward Lewis, a rich businessman who has trouble with relationships. Played by Richard Gere, he is our Alfredo surrogate.

The two spend a night together and then ultimately Edward asks Vivian to spend the rest of the week with him to accompany him on many of his business deals. They wind up falling in love, though Edward’s commitment creates some issues for him.

Some plot elements and characters correlate somewhat to Verdi’s masterpiece, such as Barney Thompson and Phillip Stuckey between the Germont replacements showcasing the polar opposite traits of the father figure. Thompson, the hotel manager, starts off stern and dismissive of Vivian but then becomes more paternal, helping along her transformation. Stuckey is an avaricious lawyer who sees Vivian as the cause for Edward’s sudden softening in their negotiations. He attempts to take advantage of her and thus push her away from Edward. While he is far more of an antagonistic schemer, he, like Germont, makes Vivian reconsider whether she is an apt companion for a man of society.

Opera vs. Film

Tying the bow together is the fact that the opera itself shows up about an hour and 25 minutes into the film as Edward takes Vivian to the opera. We hear the prelude as Edward comments on whether people can truly love opera after the first experience before the lights go up slightly on the opening party. Then we cut to “Sempre libera” before jumping to the climactic “Amami Alfredo” and then to the grand finale, the camera moving closer and closer to Edward and Vivian as if this experience were drawing them together. Vivian cries as the opera draws to a close remarking on its impact on her. Many filmgoing audiences might not immediately draw the connection between the content of the opera and film, but for those who do it, it isn’t a particularly subtle one. But in the context of the film, it does work, particularly with the ending.

Being a romantic comedy (as opposed to the melodramatic tragedy that is “La Traviata”), Edward and Vivian wind up getting together, in the end, something that Alfredo and Violetta themselves don’t get. As Edward runs up the stairs to meet Vivian, we hear “Amami Alfredo” roaring over the soundtrack. Whereas Verdi’s tragedy intuits that a woman of Violetta’s stature could never dream of living a happy life with a society boy like Alfredo, “Pretty Woman” asserts that in today’s society, this love can last and endure. Having Edward and Vivian come together at her decrepit apartment further emphasizes that the film vouches for the continued desecration of social classes and norms that are intended to segregate.

Lack of Progress

But not all is good for the film when it comes to depicting social contrast in comparison with the opera.

The biggest contrast between the opera and the film is in its lead character. Violetta is the driving force of the opera, while Edward, who lacks the insecurity and romantic experience of Alfredo, is the power figure in “Pretty Woman,” despite its title. In fact, the title emphasizes the objectification of Vivian, to the point where she is nearly powerless and subject to the whims of men throughout the movie. In the opera, Violetta decides the fate of the romance, first deciding to run off with Alfredo and leave Paris behind before eventually cutting it off, even going so far as to take his insults in front of others after rejecting him.

In the film, Edward is the one to set the conditions of his relationship with Vivian, inviting her to his room, setting the terms of her remaining with him, then rejecting her, and then ultimately, at the climax of the film, declaring his love for her. It brings to light an issue that has plagued the film industry to this day – the subjugation of women. Moreover, it emphasizes that opera moved along from that far quicker in giving women more dramatic power.