Opera Holland Park 2023 review: Rigoletto

Cecilia Stinton’s Smart New Production Frustrated by Uneven Vocal Turns

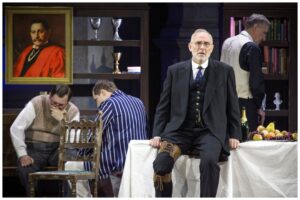

By Benjamin PoorePhoto: Craig Fuller

Opera Holland Park’s (OHP) 2023 season opened with Cecilia Stinton’s new production of Verdi’s “Rigoletto.” It leads a pack of new productions including “Hansel and Gretel,” the world premiere of Jonathan Dove’s new opera “Itch,” and “Ruddigore,” another G&S collaboration with Charles Court Opera.

Stinton’s handsome production (designed by Neil Irish) is “Rigoletto” by way of Evelyn Waugh – think Mantua College, Oxford. The titular fool is a College Porter, whose leg-brace and war medals suggested an injury sustained in the Great War, hinting at an external cause for his distress. It also makes him, ultimately, another kind of victim of the entitled British ruling class that make up the Duke and his courtiers, who resemble a Bullingdon-club-style drinking society of student who revel in rituals of sexual and physical humiliation meted out to women and each other (in a bracing opening scene of their peers is initiated into the club by having his head brutally dunked in a water bucket).

Entitlement & Cruelty

The opera’s themes of entitlement and cruelty, with a big dollop of misogyny on top, sit well in this setting, which has a special political valence given the background of many senior politicians – two recent prime ministers – in this milieu. Sometimes it’s more Wodehouse than Waugh though – Monterone is rather comically paraded around in his underpants, wrapped in bunting, and beaten with boathouse oars in Act two, which rather mutes the music’s sense of doom.

OHP have retained their set up from the last couple of years, with orchestra in the middle, with an apron at the front, which gives us the interior of Rigoletto’s home, closed off from the rest by two grim metal gates. It’s a good way of framing Verdi’s favorite tension between public and private, and the masks that need to be put on to traverse these arenas.

There are plenty of zippy period touches worked into the production. The pub in Act three is kitted out dartboard and cigarette posters, and sharpens the class divide between town-and-gown in the piece. the banda for the opening scene is replaced by a swinging jazz-band piped through the gramophone as the chorus cavort about in a smartly-choreographed party scene (the wide, distant upstage area isn’t easy to fill without it looking too busy, Caitlin Fretwell Fresh’s movement and a complement of actors make the world feel lived in, heightening Verdi’s feel for psychological realism).

The fixed audio elements that proceed each Act – party noises at the start, a frightened heartbeat after Gilda’s abduction – are less successful, adding nothing to a score already precision-tooled by Verdi for tension and insight. Jake Wiltshire’s lighting, though, is a great boon – stark and dramatic – and stops the setting from feeling too “Jeeves & Wooster” or operetta-ish (one could surely stage “Die Fledermaus” using the same basic set.)

Stinton handles Gilda especially well. We first see her coming back from a party, hiding an empty champagne bottle and flapper sunglasses before putting on the demure, bookish persona expected by her father; we have the sense she is already making her way in the world, despite her father’s misguided, suffocating insistence that she stays in and reads books. Her ultimate sacrifice therefore seems to come from a place of maturity and agency. In the final scene, she rises as if transfigured, Rigoletto clutching the bloody sheet in which she was draped – she is finally separated from her father, even if only in death, and made into someone wholly new.

Mixed Singers

It’s a convincing vision of the opera, but let down badly on the night by baritoneStephen Gadd’s performance. Clearly unwell, though with no announcement, he struggled to sing above the stave and was forced into a gamut of unmusical compromises, transposing whole passages down an octave and foregoing many of the role’s most thrilling and intensive top notes. Gadd is a fine actor and tried to fold some of the vocal shortfalls into the role – his “taci,” normally a top F in Act two’s “Cortigiani” sequence, was a pathetic (in the right sense) moan of anguish. But this was a pale imitation ultimately. Whilst not every version of the role has to foreground Olympic vocal gymnastics, there are moments – the climaxes of Acts to and three – that really call for baritonal eruptions. It felt like a night where Gadd should’ve stepped aside for a cover to take his place; one can only hope his health improves for the rest of the run.

Alison Langer’s Gilda was a different story, happily. The vocal assurance – bang in the middle of the note – is the perfect match for the character’s burgeoning personhood in Stinton’s production, and her coloratura in “Caro nome” – especially the nosebleed-high trills – was razor-sharp. When she needed power it was there in spades, defiantly soaring over the orchestra in the Act two finale as she makes the case for mercy over vengeance (vocal and moral strength of a piece). Her dying duet with her father shimmered – a searing performance.

Alessandro Scotti di Luzio gave a slightly uneven account of the Duke. He’s believable enough as a posh Oxford boor, with the power and mettle of his voice translating well to the boisterous swagger of the opening scene, and indeed the arrogant self-assurance of his meeting Gilda; he also put on a good show prancing for the pub goers in “La donna è mobile,” who are both incensed and intrigued in equal measure by this toff in his scarlet hunt coat. But often he sang just slightly under the note, with the heft of his voice proving rather inflexible, particularly when pushing for the money-maker top notes; by the same token, softer and more delicate colors at other moments would’ve been welcome indeed.

Smaller roles see some familiar faces at Opera Holland Park, and are cast with characteristic strength. Jacob Phillips’ Marullo is a malevolent presence, with a baritone as precise and neatly-clipped as his mustache (he is a young singer who continues to impress, and I look forward to hearing him debut in a more substantive Verdi role.) Matthew Stiff brings his cavernous, charismatic bass to Monterone (following an opulent Prince Gremin last year in “Onegin”), even if the direction does quite marry his intensity to the production.

Simon Wilding’s Sparafucile boasted a mean bottom F, and rolled out the old bravura trick of singing it upstage while walking off at the end of his aria – if you’ve got it, why not flaunt it? The men of the Opera Holland Park Chorus – complemented by a troupe of actors – inhabit music and action with ease, and populate Stinton’s world with conviction. Hannah Pedley’s Maddalena brought a velvety, seductive quality to the Act three quartet.

Lee Reynolds conducted Opera Holland Park’s regular orchestra, the City of London Sinfonia, in a lean distillation of Verdi’s score with single woodwinds and brass by Tony Burke. Strings were lean and mean, and the oboe solo in “Tutte le feste al tempio” was desolate and poised. Despite this being a score that often calls for great dramatic explosions of sound – think Monterone’s appearance in Act two – this reduced version spoke to the opera’s many chamber-like moments with solo spotlights, and our heightened awareness of single players helped underline the opera’s acute psychological portraiture. Reynolds took things at a considerable lick, which stops the score getting saggy in this big open space, though the opening aria was so brisk there was scant room to breathe for the Duke. It was precise playing, rather than imposing, but had a different impact accordingly; other teething troubles, such as ensemble wobbles in the prelude, will surely sort themselves out as the run goes on.

It’s a strong vision of the work, if frustrated by a couple of vocal performances.