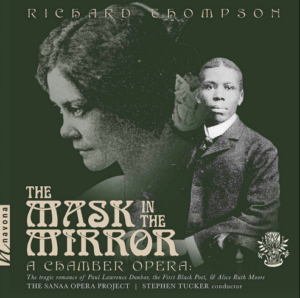

Off the Beaten Track: Exploring Race & Identity in Richard Thompson’s ‘The Mask in the Mirror’

By Chris RuelAs we wrap up June and African-American Music Month, Off the Beaten Track explores the 2019 recording of composer and librettist Richard Thompson’s “The Mask in the Mirror,” the story of the ill-fated romance between America’s first Black poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and Alice Ruth Moore, a New Orleans Creole, poet, journalist, and early civil rights advocate.

For those new to this monthly column, Off the Beaten Track looks at recorded operatic works from a variety of perspectives, and with “Mask,” examines how the concepts of race and identity shape the professional and personal ambitions of the opera’s central characters.

Before diving into the deep end of the pool, I want to introduce you to the composer, Richard Thompson, and my approach to this important work.

Richard Thompson

Born in Scotland, Thompson is of African descent. In addition to being a composer and librettist, he is a pianist and educator adept in a wide range of styles. He holds the position of Assistant Professor of Music at San Diego State University where he teaches music theory, history, and jazz performance.

Thompson injects the opera’s composition with elements of jazz, particularly Ragtime, and a quick nod to show tunes. Knowing Thompson’s abiding interest in jazz, and that Ragtime’s popularity was at its peak during the period in which Dunbar worked during the late-19th and early-20th centuries, the inclusion of these components seems very natural and necessary.

Outside jaunty interludes in Act two, the music is foreboding and tense, providing the listener with little escape from the tragedy as it unfolds.

Thompson’s libretto drives the story forward with a compelling narrative, dramatizing the fraught relationship between Paul and Alice in a manner that can be analyzed using any number of critical approaches to literature. Opera is text as much as it is music.

In the “Cambridge Companion of Opera Studies,” edited by Nicholas Till, Till states in the Introduction that “… a form like opera is inherently interdisciplinary, and therefore demands a wide range of critical approaches.”

I couldn’t agree more, so with “Mask,” the direction I’m taking is one that hones in on the characters within their historical context, and in doing so, explores race and identity — concepts that are at the forefront of global consciousness.

The Relevance of “Mask” at This Moment in History

I connected with Thompson via email, asking how he viewed “Mask” in light of the extraordinary racial justice movement occurring in the United States and around the world currently.

The opera premiered in 2012 by Trilogy Opera in Newark, New Jersey, close to a decade ago. It would have been hard to predict that less than a decade later, issues of race would overtake a deadly pandemic as the most pressing concern in the United States. Here’s what Thompson had to say.

“‘The Mask in the Mirror’ is suddenly very relevant, considering what’s happening, not only in America but throughout the whole world. I wrote it because Dunbar’s story is a great example of strength of will in the face of adversity. He showed that determination and perseverance can make a dent in a system that had woven racism into its essential fabric. He was the son of ex-slaves, who could not read. At the tender age of 21, he published his first book of poetry. Three years later, he published his second book. The review in Harper’s Weekly launched his career. Just think, not long after the Reconstruction era, a young black man made a significant difference to the American literary world. This shows remarkable inner strength, not to mention talent. It is sad that in 2020 there are still many doors closed to people of African descent in this country. Dunbar’s life is an inspiration for us now. With all the resources at our disposal, it should be possible to instigate a meaningful and lasting positive change.”

“I had another purpose in writing ‘Mask.’ America is the most culturally and racially diverse nation on earth. Yet, in the world of opera, most of the new operas are about white America. This does not reflect the country we live in. There have been a few operas written and performed since I wrote ‘Mask’ that deal with the black experience. Anthony Davis’ ‘Central Park Five’ and Terence Blanchard’s ‘Champion’ are two examples. It is wrong that African-American life is relegated very often to stereotypical images in film and in the theatre, or is completely ignored. There is so much more to the culture that needs to be portrayed.”

Paul Dunbar was well-aware of the stereotypes of which Thompson speaks. So, let’s begin with Paul’s battle to establish himself as a Black literary poet in the white-dominated, clubby culture of American letters and the impact it had on his identity.

Paul Versus the Literary Establishment

In Act one, scene two, literary critic Dean Howells sits in his gentleman’s club with a book of poetry in his hands. The book has no date, place, or publisher attached to it, but it grabbed Howells’ attention.

He knows it has been written by a Black man named Paul Dunbar — he studies the picture of Dunbar printed on the interior of the volume. Howells comments on Paul’s features — his hair, his lips, his eyes, noting “the pure African look.” The critic goes on to say:

“I would have thought the poet

about twenty years old.

He would have been worth,

Apart from his literary gift,

Fifteen hundred dollars

under the auctioneer’s hammer!

It is in his plantation poems

that we feel ourselves

in the presence of a man

with authority.

Mr. Dunbar opens vistas into the simple,

Sensuous, joyful nature of his race.

He has brought us nearer

To the primitive human nature

In his race than anyone else.

Mr. Dunbar writes literary English

when he is least himself.”

The review incenses Paul. Howells praises and denigrates the poet’s work in one fell swoop. Recognition as a literary poet drives Paul’s work; he doesn’t want to write and be known solely for his dialect poetry — his Plantation Poems.

At a poetry reading in Act two, scene one, Paul’s literary work is met with palpable silence and then polite applause. At that moment, he knows what it is they want to hear and he decides to give it to them.

“Oh, it’s sweetah dan de music

of an eradicated band;

An’ hit’s dearah dan de battle’s…”

Upon concluding the poem, the applause is enthusiastic and loud.

“All they want to hear is dialect, dialect!

I wish I had never written those damn things.”

Dunbar’s publisher’s representative waits offstage and as Paul bangs a table with his fist, the representative reminds him that it was the Plantation Poems that bought him the comfortable house in Washington DC, as well as the nice suit he wore.

“Nobody cares about black Byron or Longfellow,” the rep states.“I have my own identity, you fool,” Paul responds.

I surmise a second battle going on, a battle within Paul’s soul. While he vehemently states he has his own identity, does he truly know who he is? Is he ashamed of his blackness? Does he wish he could shed it so he can be placed in the pantheon of great poets such as Byron and Longfellow? Perhaps the answer resides in the woman he chooses to love, Alice Ruth Moore.

The New Orleans Creole & Racial Identity Within the Black Community

Alice Ruth Moore was a New Orleans Creole. She fell in love with Paul from afar after she wrote to him regarding her own writing. Paul responds favorably to her work and the two begin corresponding, writing love letters, and sending pictures. Both appear head-over-heels in love.

However, both Paul and Alice’s friends and family have doubts about the viability of the relationship.

In Act one, scene three, Paul’s friend Victoria chastises Paul. Victoria knows he’s a womanizer because she was one of his conquests. She says something very important related to racial identity when speaking of Alice:

“What makes this little creole special?”

Why does Alice’s Creole heritage matter?

Creoles, or Creoles of Color, was a descriptor used by a subset of Free People of Color living in New Orleans and South Louisiana. Both the Spanish and French assigned different meanings at different times to the term, but by the 19th century, the name denoted a person with mixed ancestry, particularly a blend of West African and European heritages.

Creoles owned property, were well-educated, and played a vibrant role within New Orleans society, contributing to the economic health and prosperity of the city as merchants, artisans, and businessmen. That all changed when the United States took possession of the territory. The Louisiana state constitution declared anyone with 1/8th African heritage as Black — period. The law stripped Creoles of their societal privileges, their property, their status, and their freedom.

While the state constitution determined what percentage of African blood made a person Black, those of African ancestry drew racial lines according to varying degrees of skin color. Creoles resided in a societal limbo: they were either too white to be considered Black, or too Black to be considered white.

It is against this backdrop that major tensions arise. Alice sees herself as better than those of darker complexion. In fact, she despises them. But in the truest sense of the term, Alice isn’t a Creole. She is the daughter of a formerly enslaved woman and an ordinary sailor. Her identity as a Creole is her mask. We see this play out in Act one, scene five when Alice, working as a school teacher in Brooklyn, enters into a vicious argument with the new headmistress.

ALICE: I hate to work under negro women

And my heart sinks at the prospect!

MS. LYONS: You would insult me for being

who and what I am.

Too dark for you to respect!

ALICE: Yes, you and all the other inkspots here

I detest you all.

MS. LYONS: You are deceived by your fair beauty,

you have lost yourself in the mirror,

with all this creole nonsense!

you are no creole.

It’s all a stupid lie!

The argument continues in this vein with Alice stating she would work for someone who is white, stating, “I can always get along with white people.”

If Alice cannot stand Black people and sees herself as their better, why would she fall in love with Paul? Imagine if Paul were not a famous poet, just a mediocre Black writer known for his drinking and womanizing. Would Alice have given him a second glance? Based on the above exchange, I’d venture to guess not. There is an element of hero-worship driving Alice’s desire to be with Paul. She states multiple times that she is marrying “The poet laureate of the negro race,” intimating that through their union, she will gain success as a writer. Her mother, Patsy, challenges the relationship and says as much.

“You give yourself to fame

And lose yourself in shame.

Your unwed mother looks on in pain

While my false little creole looks for gain.”

Here again, Alice is called out on her claims of Creole heritage, this time by her own mother.

In the tragic end, Paul’s struggle with his identity as a Black poet collides with Alice’s self-styling as a Creole. Paul rapes and abuses Alice as his drinking and anger intensify. Alice’s pain and suffering at the hands of Paul become too much to bear.

The final climactic scene that takes place in front of Paul’s mother, Mathilde, is gut-wrenching. All the dreams of love and success have been shattered and the masks are removed.

ALICE: “May the former slave

Love her darling little Black boy!”

MATHILDE (TO PAUL): “See how your sorrow and anger eat away

At your consumptive lungs!

This is the price you pay

For your lightskinned trophy!”

PAUL: “I know, ma, I know.”

Alice separates from Paul, and as he sits dying with a drink in his hand, he speaks his final words.

The creole and the ethiop.

We both do love and despise each other.

And the self that cries out

Lies buried within.

The lies of our past

Turn our radiance to grief.

Faced with crushing societal pressures, racism, alcohol abuse, violence, and the underlying racial tensions within their marriage, it was only a matter of time before Paul and Alice’s relationship imploded.

Despite the inner turmoil and confusion, Paul Dunbar and Alice Ruth Moore’s legacy is as Thompson wrote in his response to my question; they were pioneers who fought the system and came out on top.

Paul Dunbar is known as a great poet. That is something that can never be taken away from him. He paved the road on which future Black poets would travel.

Alice went on to champion civil rights, found success and respect as a writer and journalist, and wrote openly about her struggles with racial identity. The tale of Paul Dunbar and Alice Ruth Moore’s tumultuous journey broke ground that is now producing the fruit of change. Their story is one that is deep and rich. Thompson’s opera is one for our time.

Personal Reflection

At the time of this writing, books on race fill The New York Times Best-Seller List. To say there is a racial reckoning of tectonic proportions happening is not hyperbole. Navigating the complexities of race relations is difficult work. The questions are complicated, requiring answers that arise out of reflection, sensitivity, knowledge, and understanding.

I invite opera lovers to not just read but to listen — listen to “The Mask in the Mirror.” We know music and opera have incredible power, the power to challenge, to feel, to bring us together as people. It can help do so now. Opera doesn’t belong in a museum. It’s a vibrant art form that can bring about change, but as is often said, change begins within the individual.

For me, Thompson’s “Mask” was another point on my journey of understanding race, history, and privilege. What mask am I wearing? Where are my racial blind spots? It’s a question I’ve been asking myself a lot lately as I look in the mirror.

“The Mask in the Mirror” features tenor Cameo Humes as Paul and soprano Angela Owens as Alice. Richard Thompson is on piano while Stephen Tucker conducts the Sanaa Opera Project. The recording is available on Navona Records and distributed by Naxos.