Metropolitan Opera 2025-26 Review: The Magic Flute

A Cast of Young Stars Shine in Holiday Production

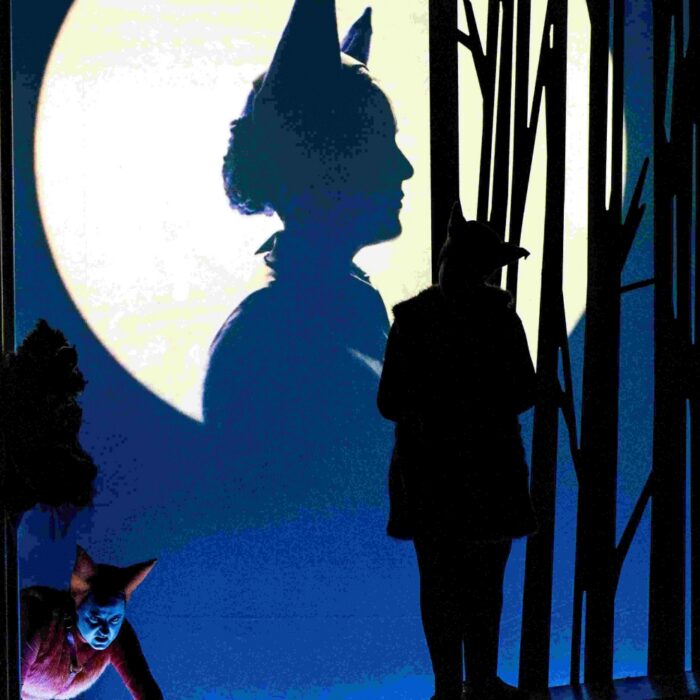

By Chris Ruel(Photo Credit: Ken Howard / Met Opera)

Every year, the Met Opera ushers in the holidays with its abridged, English-language production of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute,” delighting children and adults alike. This season was no exception. If anything, the 90-minute performance offered a welcome reprieve from a world that seems to have lost its bearings—and, oddly, slid back toward the superstition and ignorance Mozart’s fairy tale confronted when it premiered in 1791, at the height of the Enlightenment’s push for reason and knowledge. As fairy tales go, good prevails over evil, offering a small hope that the same might yet prove true beyond the opera house—fingers crossed.

The December 18, 2025, performance was as charming as its predecessors and featured several fresh faces, notably Rainelle Krause, who made her Met debut as the Queen of the Night and made an immediate impression. Mid-run, the production showed no real rough edges. At times, the energy and volume ebbed and flowed, but never to the point of dragging. Some moments that usually draw the biggest gasps—the Three Spirits atop the giant goose, the ballet of the birds, and even a few showpiece arias (save for the Queen’s)—received more restrained reactions. That had less to do with the quality onstage than with the audience itself: many were newcomers to opera, including a sizable number of children, who are understandably less inclined to shout “bravo.”

One striking aspect of the house was the noticeable lack of international visitors. The holidays are typically prime season for tourists in New York, yet while the performance was well attended, the usual mix of accents and languages was absent—a dispiriting reminder of the United States’ increasingly hostile border policies.

Fresh Faces Delight

In the pit, Steven White led the Met Orchestra, looking elegant in white tie. Although the overture is omitted in this abridged version, the orchestra launched the evening with spirit and precision, drawing out Mozart’s wit and buoyancy. Under White’s baton, shifts in color, volume, and pacing were precise and fluid. He navigated the orchestra through lively passages while giving singers space in colle voce moments, shaping tempo with care, stretching fermatas and rests in ways that heightened the drama.

The holiday run featured Julie Taymor’s beloved production, which continues to resonate with younger audiences and opera-curious newcomers. The puppetry remains enchanting; the Queen’s costume, spectacular; the Dada-inflected geometric chorus attire, intriguingly odd. Sarastro’s robes paid direct homage to kabuki theater, as did Tamino’s white-painted face and makeup.

Tenor Paul Appleby and soprano Joélle Harvey led the cast as Tamino and Pamina. Krause’s Queen of the Night soared, while Alexander Köpeczi’s Sarastro explored the depths with equal authority. Baritone Michael Sumuel brought warmth and humor to Papageno, the good-natured but hesitant bird catcher. Thomas Capobianco relished the grotesquerie of Monostatos, and Harold Wilson completed the cast as the Speaker.

Individual Performances

Appleby as Tamino was notably confident—secure in his love for Pamina and his sense of duty, and assured enough to face the Brotherhood’s trials without hesitation. His naturally heroic timbre, less brassy than noble, reinforced this characterization. “This portrait’s beauty (Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön)” was delivered with sincere longing, lending credibility to love at first sight—even when sparked by a painted image. His acting matched his vocal assurance, presenting a hero who was resolute without arrogance. This Tamino also showed less patience for Papageno’s dithering, urging him to focus on the task at hand.

Harvey’s Pamina mirrored that confidence. She emerged not as a naïf, but as a young woman navigating between two worlds: her mother’s realm of supernatural menace and Sarastro’s vision of enlightened order. When vulnerability was required—particularly during Tamino’s imposed silence—Harvey allowed Pamina’s despair to surface fully. Believing herself abandoned by Tamino and Papageno alike, she teetered on the edge of hopelessness. The closing bars of “My heart is full of sadness (Ach, ich fühl’s),” as the strings descend into hushed desolation, never fail to pierce the heart.

The evening’s undeniable centerpiece was Krause’s Queen of the Night. “The wrath of hell (Der Hölle Rache)” is her calling card—one she knows so well she has sung it upside down in solo performances. An accomplished aerialist, Krause brought that physical confidence to the role, handling the demands of the staging without sacrificing pitch or clarity. “You, you, you (Du, du, du)” merited far more applause than it received. In the big aria, she offered a reading that felt entirely her own, with no trace of imitation. Though the role is very familiar to her, having performed it with houses ranging from Deutsche Oper Berlin to North Carolina Opera, the Met appearances confirmed her as a fast-rising Queen.

If Krause owned the upper register, Köpeczi’s Sarastro claimed the depths. While high notes often provoke the audience’s anxious anticipation, the courage required to sustain Mozart’s lowest lines is frequently overlooked. These notes are prolonged, leaving nowhere to hide. In “Within our sacred temple (In diesen heil’gen Hallen),” Köpeczi delivered a calm, grounded authority that filled the house.

Sumuel as Papageno served as the production’s comic anchor. Less clown than everyman, his bird catcher felt like someone accidentally swept into an epic journey. His entrance aria, “I am Papageno (Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja),” landed as a burst of uncomplicated pleasure—a joyful song sung by someone genuinely happy with his job and his place in the world. Though a supporting role, Sumuel gave Papageno a clear arc, creating the sense of parallel adventures unfolding alongside Tamino’s. He even slipped in a sly contemporary joke—counting “six, seven” between two and three as Papagena’s arrival neared—clearly aimed at the younger crowd, who caught it immediately.

Closing Thoughts

At a broader level, one scene remains questionable for a family audience: Papageno’s aborted suicide attempt. Unlike past interpretations, Sumuel did not place the noose around his neck, nor linger beneath the dangling rope. The moment he touched it, Papagena appeared, cutting the scene short. His handling was sensitive, but the inclusion still feels misplaced. Given how much music and material is trimmed in this version, it’s puzzling that one of the opera’s darkest moments remains. A brief overture showcasing the orchestra would be a far better use of time than implying suicide as a response to heartbreak—especially for children. In an era of ubiquitous content warnings, it’s surprising this moment passes without comment.

The Met’s holiday Magic Flute has long been a reliable offering, and this year’s production upheld that standard. If anything, it felt especially consoling. In uncertain times, the reminder that love and knowledge can outlast cruelty and ignorance still resonates. Sometimes, it takes a fairy tale to say what needs saying.