Metropolitan Opera 2022-23 Review: Tosca

Aleksandra Kurzak, Michael Fabiano & Luca Salsi are Outstanding in Met revival of ‘Tosca’

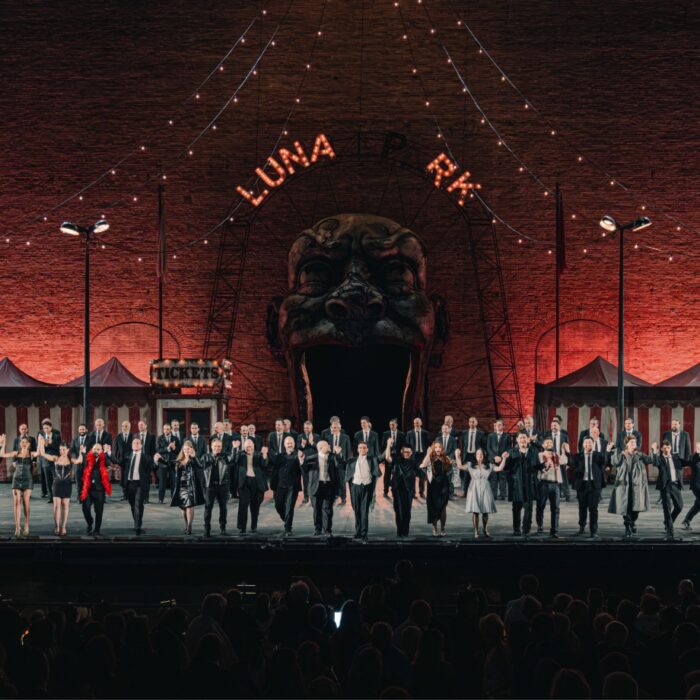

By Chris Ruel(Credit: KarenAlmond/Metropolitan Opera)

A “shabby little shocker.” That’s how musicologist Joseph Kerman described Puccini’s “Tosca.” Shabby? No. A little shocker? No. It’s a big shocker. Perhaps we’ve become inured to how dark and violent “Tosca” is with scenes of rape, murder, torture, and suicide. There was no mistaking the grittiness of Puccini’s fast-paced thriller at the Metropolitan Opera. The October 4, 2022, show was “Tosca’s” season premiere and performance number 944 of Puccini’s potboiler at the Met.

The show had a rock star principal cast: Michael Fabiano as Cavaradossi, Aleksandra Kurzak as Floria Tosca, and Luca Salsi as Scarpia. On the podium was Carlo Rizzi.

Some opening nights can feel like a final dress with kinks in need of smoothing. That wasn’t the case in this production. Unfortunately, the crowd on hand was light for such a well-known show, but it was a Tuesday evening when typically the hardcore fans settle into seats as opposed to date-night attendees, and judging by the raucous applause, the buffs were more than pleased.

The grittiness of “Tosca” is the apex of verismo, providing an unvarnished slice of life in an authoritarian regime at the turn of the 18th century. The opera has a depth not present in the composer’s other works. Librettist Giuseppe Giacosa thought there was too much plot (and subplots) but Puccini was determined to take Victorien Sardou’s stage play, “La Tosca,” and mold it into an opera. Puccini completed the work in 1899 and “Tosca” received its premiere in Rome at Teatro Costanzi in January 1900.

While the opera received a so-so reception from critics, the public liked it and the show ran for twenty auditorium-packed performances. When the opera moved to La Scala, under the baton of Arturo Toscanini, the famed house was full for each performance, likewise when the production moved to London. “Tosca” came to New York’s Metropolitan Opera in 1901, and by the start of World War I in 1914, the show had visited 50 cities across the globe. It has never left the repertoire.

Realism and the Alpha Male in “Tosca”

Author Peter Conrad, in his book “A Song of Love and Death: The Meaning of Opera,” calls out the atavistic nature of Puccini’s realism. He calls the composer’s characters “emotional primitives, sensual savages.” Conrad identified two undercurrents that drive verismo, stating, “Realist opera is almost sadistic in its defiling of people,” and “The subject of realist opera is a pathological desire.”

“Tosca” ticks each of Conrad’s boxes, and it didn’t take a wild reinterpretation of the work to bring out the animalistic contours of Puccini’s “Tosca” characters. David McVicar’s production, with sets designed by John Macfarlane, is a traditional staging, and rather than making the production ho-hum, it allows the audience to focus on the narrative, not the trappings of the sets, not that Macfarlane’s are aesthetically boring quite the opposite. He recreated the Church of Sant’ Andrea della Valle, faithfully, though not exactly; Scarpia’s chambers in the Palazzo Farnese are sumptuous, and the Castel Sant’ Angelo is accurately replicated. Puccini replicated the exact pitch of the great bell at St. Peters in his quest for realism. Rome is to “Tosca” as Florence is to “Gianni Schicchi.”

Deciphering Conrad’s notions of realism in “Tosca” is straightforward. Tosca is driven by jealousy and passion for Cavaradossi. Scarpia has a pathological desire not to love Tosca but to destroy her, and Cavaradossi is driven by his own pathological passion for Tosca. The very atavistic battle between Scarpia and Tosca reaches its apex when Scarpia attempts to rape Tosca. Scarpia is used to taking what he wants, and he wants to conquer Tosca as he has many others. As he states at the beginning of Act two, with women, he likes a smorgasbord. “Hence I must strive for the thing I desire/I possess it, and then discard it/turning to other pleasures/God created beauty and wine of various merit/I choose to taste all that I can of the heavenly produce.” Don’t be fooled into thinking Scarpia is merely a lech. He revels in power, and rape is at the top of the list of heinous ways to exert power and defile. It’s the primitive drive to be the “alpha male,” to take what he wants by force, including women.

The Challenge of the Knife and Candles

Act two is brutal. Scarpia was at his most satanic and Tosca at her most vulnerable. It’s visceral and hard to watch. Though it doesn’t register as a mad scene in the traditional sense, it is. Kurzak’s approach to Act two was entirely believable, and believability is crucial. Fred Plotkin, in his Opera 101, has an interesting look at how small things matter. He specifically pointed to the knife and candle scene and the singer’s interplay with the props. If realism is key, her reactions should be realistic. Let’s look at how Kurzak handled the moments.

The knife. When Tosca spies the knife on the table, it would be cartoonish to use grand gestures. It’s subtle as it might be in real life. Kurzak’s circling the room, and as Scarpia prowls panther-like, looking for another opportunity to pounce, she glimpses the knife. As she passes where it lies on the table, Kurzak stops. You see her thinking. She glances back, reticent, but decides to take the chance and picks it up. As Scarpia comes at her, he receives “Tosca’s kiss.”

Kurzak went full bore, stabbing, jamming, and screaming. The knife slides into Scarpia’s gut. “That’s the way Tosca kisses!” Tosca jams the knife into his neck. “Your own blood will choke you!” Tosca stands over Scarpia. “Die in damnation, Scarpia. Die now!” As Scarpia lies dead, she’s shaking, she’s confused, and a bit sickened by herself. Whoa. Even by today’s standards, that’s hardcore. Watching Kurzak’s Tosca break with reality and turn into a blood-crazed assassin was one of the most powerful scenes in the production. She was so good, you wanted to tell her, “Ease up. He’s dead already.”

The candlesticks. Like the discovery of the knife, Kurzak avoids the kitsch. She has her hand on the door before she takes notice of them. There’s a moment of introspection, and then she takes up the candles. A singing-actor has to be intentional in Act two. The spell of the scene can be wiped out instantly by cartoonish, unrealistic moves and reactions. Should you see a production, pay close attention to how the singer navigates the knife/candle acting challenge.

Karen Almond/Metropolitan Opera

Operatic Heresy

Let’s be opera heretics. What if “Vissi d’Arte” were eliminated from the scene above? Wait, don’t clutch pearls just yet; there is precedence. While Callas wanted the aria cut because it distracted from the action, it was Leontyne Price who actually had it removed and did it as an encore. It was the right call.

Kurzak and Luca Salsi built Act two into a frenzy of emotion. It was edge-of-seat opera. Kurzak and Salsi have you completely sucked into the drama. Then, an exquisite but ill-placed aria breaks the action in the worst place possible. It absolutely does. Including the aria smashes the magic. Devastatingly so. The impassioned back-and-forth is interrupted, the aria sung, and it’s back to Scarpia terrorizing Tosca. “And now back to our regularly scheduled program;” that’s what it feels like. Nixing “Vissi d’Arte” is a non-starter, so there’s not much to worry about. If you disagree, that’s fine, but give it a few moments of thought. What if “Vissi” didn’t split Act two? And instead of waiting for the big takeaway number, you allow the power of the Act to bring you into the opera.

She Lived for Love

Continuing with“Vissi d’Arte,” Kurzak crushed it. Because the aria is so beloved, the pressure’s on. Ways to mar “Vissi d’Arte” are plenty: oversinging, going beyond melodrama and into parody, poor use of dynamics and shading, bad tempi, park-and-barking, etc. The purpose of arias is to bring the audience into the character’s head, which means the artist must remain in character and not hand the audience a beautifully sung concert piece. Tosca must remain Tosca. That means Kurzak must remain Tosca, not Kurzak singing an aria from “Tosca.” Breaking character and not singing with the same personality developed through more than half the show would be a letdown. If an artist has developed a fiery, defiant Tosca, that fire should be reflected, not discarded in the name of pretty singing. Kurzak sidestepped all the pitfalls and delivered an emotionally moving presentation.

Kurzak’s was a tempestuous Tosca whose emotional state was always in flux. In Act one, she’s playful yet dominant. Cavaradossi would do anything to keep her happy and not wildly jealous. She was furious that Cavaradossi’s Magdalene looked like Marchesa Attavanti and ordered him to change her eye color from blue to dark. Cavaradossi does as told. Entering Act two, Kurzak’s Tosca is defiant. She’s thinking of ways to outsmart Scarpia, but that doesn’t remove the fear. When we arrive at “Vissi d’Arte,” she’s been worn down, outmatched, and realizes all may be lost. And that’s how Kurzak expresses the music.

The score sets the initial tempo at Andante Lento Appassionato/40 quarter notes per minute and instructs the vocalist to sing sweetly with huge sentiment. Kurzak and conductor Maestro Carlo Rizzi kept the tempo right. Did Kurzak sing it sweetly? It’s not a sweet moment. Kurzak’s shading was introspective, and sad, and expressed the uncertainty of the future. The beauty was in the sadness.

Of particular note, Kurzak’s forte high B flat on the second syllable of Signor was a heartfelt cry, and two bars later, she let the E drift into the ether with stunning pianissimo.

A Place Among the Greats

Michael Fabiano as Cavaradossi. One word: supernatural. Anyone who’s heard him knows the sheer power of his voice. At the closing of “Mario! Mario! Mario!”, with all eyes focused on Kurzak, Fabiano came out of nowhere from stage right with a stupendous, forte high B flat on the “Ah!” of “Ah! M’avvinci ne’tuoilacci.” Fabiano possesses an instrument handed down from the greats. It’s thrilling, it’s brilliant, and he stands among the most esteemed tenors of our time. That’s why we love to see him in action. However, the same awe-inspiring B flat destroyed any chance of hearing Kurzak, not because she’s not powerful enough for the role, but because Fabiano can overpower almost anyone on stage. As the evening progressed, adjustments were made and the Fabiano/Kurzak pairing was more balanced.

Fabiano’s entrance was fiery, confident, and in charge. His Cavaradossi got in people’s faces. He was not a timid painter; he was a painter with an attitude, unless with Tosca. Her coquettish playfulness held threats, which he took seriously.

Tenors face an early test in “Tosca.” They need to come out ready to sing “Recondita armonia” with its high tessitura, high A’s, and a big B flat towards the end, which Fabiano sat on. Was he grandstanding in doing so? Perhaps, but let’s put his bravura Act one in context. Fabiano is a North Jersey guy, so singing at the Met is a homecoming of sorts. Of course, he’s going to put on a barnburner performance for the home crowd. But also, this was a rainy Tuesday evening performance, with empty seats. Things felt weighed down, not just subdued, but heavy. Fabiano changed that. The electricity he brought flowed into the audience and got the blood pumping. His singing was a delight for the ears and caviar for the musical mind. This is what audiences come to hear, and Fabiano delivered it in spades. Likewise, with “Vittoria! Vittoria!”

“E lucevan le stelle” is to Cavaradossi as “Vissi d’Arte” is to Tosca. It’s the big tenor moment the audience waits for all evening. Fabiano showed his versatility, both with his acting and his singing. Gone were the trumpet blast notes of the happy and in-love painter. The piece is gut-wrenching and one of the most beautiful tenor arias. Fabiano took it slow, letting the audience take in his lovely legato lines. When singing the words “… forme disciogliea dai veli,” Fabiano used his head voice to sing the high notes—the top note being a high A. It was a surprise and going falsetto gave the impression of shying away from the topmost notes. Whatever the reason for the head voice, he sang a full-throated high A a few bars later, and, again, he sat on the note, and it felt right, not showy. Passion filled each note.

He Deserved Every Stab and Then Some

Baron Scarpia … Just saying his name makes you want to take a shower. Sadistic, satanic, and plain gross, Scarpia is one of opera’s top villains with absolutely zero redeeming qualities. Anyone taking on the role needs agility as Scarpia switches from terrifying to smarmy to evil personified.

The reigning Scarpia is Željko Lučić, but coming up behind him is Luca Salsi, an Italian baritone whose rep has included Sharpless (“Madama Butterfly”), Scarpia (“Tosca”), Germont (“La Traviata”), Rigoletto (“Rigoletto”), and Amonasro (“Aïda”).

When Salsi entered Act one, he might as well have been Darth Vader. Scarpia had arrived, and he was not fooling around; he was out to mess people up, dominate them, make them cower, and bend to his will. Get in his way or on his bad side, and you had better run before his goons grab you and send you for a painful visit with Roberti, Scarpia’s torturer-in-chief. Salsi’s Scarpia is unforgettable. His stature commands the stage, and his deep baritone is well suited for the character’s declamatory vocal line. Lust consumes him, not simply lust for sexual pleasure, but a lust for destruction, particularly that of women unfortunate enough to catch his eye. Scarpia is a master at finding weaknesses and exploiting them. He recognized immediately that Tosca’s pathological jealousy could lead to her undoing, so he uses it.

When Scarpia climbs on top of Tosca to rape her, it is too real. It’s repulsive and stomach-churning—just as it should be if we look at Puccini’s realism through Conrad’s lens. That the production doesn’t sidestep the horror of the assault, and because you get sucked into the drama like water to a sponge, you forget it’s not real. After Tosca escapes his grasp, spots the knife, and prepares to use it, you cheer her on. Give it to him, Tosca! Kurzak’s Tosca loses herself in the violence and becomes Scarpia in her cruelty. Knifing him in the neck, mocking him, and watching him choke on his own blood is brutal. Good for her. Such feelings are a testament to Kurzak’s interpretation of the character. If she were a run-of-the-mill Tosca, you wouldn’t catch the same vibe as Kurzak sent into the audience. She elevated Tosca from victim to hero.

Karen Almond/Metropolitan Opera

The Orchestra as a Character

“Tosca” is regarded as Puccini’s most Wagnerian work. Puccini employs motifs to great effect. Scarpia’s theme is found in the opening bars with its raucous chord progression. The love theme appears first in “Mario! Mario! Mario!” Angelotti has a theme. Places, and even the character’s inner thoughts are represented. Unlike Wagner, Puccini’s themes are static, whereas Wagner worked with his motifs, expanding upon and shaping them.

“Tosca” is very much like a television show or movie, and that makes sense since it was born of Sardou’s play. The vocal lines are more like speech, with scant lyricism save for the takeaway arias. This significantly pressures the orchestra to stand out without overpowering the vocalists. Timing is key in Act two since the orchestra is providing the soundtrack. So much of Act two’s impact is delivered through the orchestra. The conductor needs to be an excellent storyteller, and Rizzi is such a conductor. He didn’t force the music from the players; he enticed the beauty to reveal itself using elegant gestures, not wild arm waving. Overall, the maestro led the orchestra in a well-balanced performance that stayed faithful to the score unless freeing the singers to set off some vocal fireworks.

Supporting Cast

A Met production of “Tosca” wouldn’t be complete without Patrick Carfizzi as the curmudgeonly Sacristan, and he was delightful as ever, bantering with Cavadarossi and doing his best to keep things in order at the church.

Angelotti, played by Kevin Short, was quite good vocally and added a subtle dash of humor as he appeared annoyed at Cavaradossi for repeatedly pushing him into the Attavanti chapel, especially when the reason for hiding was Tosca. Short gave Angelotti a face that questioned who was more important. Me or Tosca? When pushed back into the chapel, he got his answer.

Rodell Rosel’s turn as Spoletta was well played. As Scarpia’s toadie, Rosel gave off a menacing vibe. His Spoletta seemed to like his job as a sadistic sycophant.

As Sciarrone, Christopher Job gave a solid performance as the gendarme.