Metropolitan Opera 2022-23 Review: Die Zauberflöte

Crowned by a Top Rate Cast, This is the Best Met Opera Production in Ages

By David Salazar(Credit: Karen Almond)

It’s fair to say that the 2022-23 season at the Metropolitan Opera can be dubbed “The Mozart Season.”

“Idomeneo” took the stage on the second night of the season with a tremendous cast reviving Jean-Pierre Ponelle’s classic production. During the holiday season, the Met turned to its workhorse Julie Taymour production of “The Magic Flute.” And to close it all out, Met audiences have been treated to two modern takes on classics, both completely different in approach, but equally effective, magical, and humanistic in their own right.

While Ivo Van Hove employed a minimalist bent to deliver a message of light at the end of a dark tunnel for his “Don Giovanni,” Simon McBurney’s “Die Zauberflöte,” goes full blast for a modern retelling of this classic opera that confronts its seriousness (and problematic nature) while also enjoying its self-awareness. I won’t hide the fact that I think that it’s the greatest production that Met Opera has brought in years; quite possibly the greatest artistic success of the Peter Gelb administration. And the irony in all this, is that isn’t some massive revolution. In fact, a lot of elements that make it so good won’t be new to Met audiences in the least.

Without Any Warning (Lots of Spoilers Ahead)

The experience starts from the moment you enter the main hall, the stage opened up to the audience, the orchestra pit raised up so that musicians are in close proximity to the stage. There’s an apron around the pit, similar to what Bartlett Sher’s “Barbiere di Siviglia” production employs (but never fully takes advantage of). But the real shockers for the viewer are the two work stations at opposite ends of the stage – these will become vital to the overall experience. On stage right is a video camera, a chalk board, and some props that will make up the vital components of the production’s visual experience, led by visual artist Blake Haberman. On the opposite end is a station that looks like a bar with bottles and a bunch of other instruments, which will be the home base of foley artist Ruth Sullivan.

And at the center of the stage is arguably its most vital piece – a massive square plank that will take on all sorts of configurations throughout the show. It will be raised; it will be inclined and rotated; it will serve to project different environments. If you’ve seen the Met Opera’s Robert LePage production of “Der Ring des Nibelungen, you’ll recall the dozen planks that mis-en-scène required to create the visual experience of the famed tetralogy; this single square manages to all that one could and more without the noise or glitching (though to be fair, it could be excruciatingly resonant when objects were dropped on it, as evidenced by an unfortunate such moment during “Ach ich fühls’” softest section).

And then came the performance itself which started more as a combined invitation / call to action. With the lights still on and the chandeliers in their initial positions, conductor Nathalie Stutzmann walked up to the podium unceremoniously and brought forth the opera’s opening E flat major chord. Suddenly the chandeliers started to rise. People shuffled into their seats. All as the overture unspooled. After the opening half of the overture, a large screen came down and the visual fireworks got underway with Haberman writing out the title, composer, “1. Akt” on the projected chalkboard, his hands moving balletically in consort with the music. This table setting initially felt a bit confusing and I had my doubts about whether it would be a long-term distraction, especially with the audience howling and laughing throughout the overture; but of course, that the self-serious opera audience member in me, and that’s precisely the one that McBurney seemed to be challenging in that moment, asking me to look around and feel the energy from the rest of the audience and to enjoy the artifice of this opera, set in a magical land far, far away.

But far, far away doesn’t quite feel like the right expression here. Because once the overture concluded, Tamino and the three ladies rushed onto the stage from the audience. Just as with the opera’s opening gesture, the audience was very much a part of the experience from the get-go and would continue to be so throughout the night. What was fascinating about this opening entrance is that the Three Ladies are all dressed in camouflage. The program notes immediately let us know that the opera is set in a world at war with two factions in conflict. And while it’s never fully explained or emphasized, this wardrobe choice and the eventual presentation of Sarastro as some political cult leader (the opening of Act two starts off in a conference room that calls out to the War Room in Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove”) gave off the vibe that the Queen of the Night (who is portrayed as old and frail, walking about with a cane or in a wheelchair, always in seeming pain) and her tribe were guerilla warriors trying to topple the established world order, which is run exclusively by dudes; if we throw in our own modern sociopolitical world and the opera’s repetitively blatant and cringey sexism, that approach is further magnified.

It also gives this “Die Zauberflöte” its own layers of complexity in the overall design. The Queen of the Night wears black throughout, but almost everyone else, including Sarastro, are clothed in black or shades of grey; only Tamino, Pamina, and Papageno escape this treatment. The main couple is almost always in white to express their purity and unifying love; Papageno, the self-aware everyman of the opera, looks and feels like the tonal outsider with his yellow vestments and the ridiculous ladder he carries around the entire time. Sarastro himself tells Pamina at one point that the “darkness” in the Queen is something that he recognizes in himself and while Sarastro is the wise leader, there’s no doubt that beneath his kindness, there is a man willing to torture people (as he does with Monastatos, though to be fair, Monastatos attempts to sexually assault Pamina several times in this opera and probably deserved the beating and so much more).

And while McBurney doesn’t quite “solve” the problem of the opera’s overt sexism (one could say that all art for most of history is replete with sexism, and that is true; but Mozart unfortunately leans into it here and in “Così fan tutte” as if it were some badge of honor), he offers a compromise at the close. Instead of killing off the Queen, Sarastro comes to his defeated counterpart and offers up an olive branch. Is it an acceptance of women as equals in a society run by men? Or an acceptance of the old ways? Or both? McBurney leaves that us to decide because the Queen accepts, comes to her feet, and seemingly rejuvenated, joins the circle and society forming and building around the newly married Tamino and Pamina. Despite its problematic nature, “Die Zauberflöte” is ultimately an opera about hope for a better society. And McBurney manages to find a way to ensure that in his retelling of this story, it’s a vastly more inclusive one than the one Mozart intended.

Before the final notes of the opera’s ending sound, the entire cast comes to the front of the stage and starts to take their bows together, providing a perfect bookend to the immersive opening.

Celebration of Stagecraft, New & Old

Music is such a big part of the thematic foundation of “Die Zauberflöte,” and this production seems to be exploring what music is exactly, especially in opera and how we interact with it. Is it just the notes in the score? Or is it the overall sonic experience that we experience around us? One might argue that Sullivan, the foley artist, is just as much a member of the orchestra as the musicians in the pit. When Papageno plays his little whistles during his entrance aria, the repetition of that five-note phrase (four 32nd notes from G 5 to D5), was played with sound effects and the bristling of paper birds from the numerous actors taking the stage. In other moments, the crashes and bangs coming from the massive sounding board at her station were essential to the opera’s entrances and exits, creating aural leitmotifs of their own. And in others, Sullivan was literally engaging with the actors in time; during one of the greatest moments of the night, as Papageno sits alone waiting for something to happen, we get an entire comedy routine with a bunch of bottles with Papageno first playing a scale and eventually leading up to him playing the introduction to his second aria with those bottles; but it’s actually Sullivan making the magic and playing the music in her workstation, further cementing her position as a musician in the overall experience.

To add to this, two musicians in particularly became major participants in the experience of the opera directly on stage. One of them was Bryan Wagorn, who played the glockenspiel solo (until baritone Thomas Oliemans, in one of the best laughs of the evening, pulled off some bravura of his own at the end of the opera) and flautist Seth Morris. Morris in particular was made part of the action during the many musical moments where the flute becomes central to the story.

And that’s just the aural experience, which no number of words will truly allow you to feel. Ditto for the visual experience, which features an endless bag of tricks. The projections of the central square are incredible, but perhaps more impactful is how the front projection screen operates in tandem with the stage. When Tamino arrives at Sarastros temple, we see massive projection of books and they pull away to reveal entryways; but in reality, Haberman is actually using real books in front of a camera to create this trick. Safe to say, the effect is staggeringly beautiful. Ditto for the trials with the use of projections on the front and back screens as well as acrobatic cables to make Pamino and Tamino literally float in space.

And then there’s the use of the video camera to spotlight the audience and characters’ interaction with the audience. It isn’t a new trick and could prove messy and sloppy (as was the case in “Lucia” last season), but here it works precisely because of how self-aware it is. When Papageno is singing his second aria and begging for a girlfriend, he walks into and through the audience. The camera follows him, allowing those who can’t see him in the orchestra (those at the top of the theater) to be able to see what’s going on. But Haberman takes this further and at one point, he kept panning between Oliesman and an audience member he had made a connection with to see their reaction in real-time; the audience member looked a bit confused and the rest of the crowd couldn’t stop laughing with glee. Remember that bit about the audience being part of the experience? I can’t imagine how that moment will play out on different nights with different audience members for Haberman to have fun with (speaking of which, people were so invested in Papageno’s character that when he calls out for help in his final big scene, preparing for suicide, some child from the upper reaches of the theater called out to try and help him).

I can go on and on – Monastatos’ dance and the chalkboard squiggles that accompany it; the brilliant move of making the children into old, wise men with synchronized movements (also echoing the Queen of the Night with their walking sticks); the three women’s indoctrination of Tamino; the use of weapons; the payoff to Papageno’s ladder; the catharsis of his scene with Papagena and the audience interaction that follows – this production is truly wonderful and I can’t wait to see it again.

Karen Almond

Showstopper

The production is nothing without the performers and they are a key to this. The director as author is a major component of the modern opera game and as such, we often find performers working for the production; given that the end goal for opera productions is repeatability with different casts, this has to be the aim. The result of course is that, outside of the musical component, their individuality as stage artists is thus inhibited. The production is the star and the singers but supporting components.

But the feeling is quite different with McBurney’s where I feel there is undeniably a give and take going on. The production has a very clear goal and concept in mind and there’s no doubt that when we talk about this “Zauberflöte,” the production will always be king in the conversation, but the means are more flexible and happening in real-time. And as such, I think it allows performers the flexibility to add their own touch and taste to the proceedings. And this is very much what we got.

No one is going to replicate the performance that baritone Thomas Oliemans gave on that opening night. Maybe not even he will be able to. Brimming with energy from the off, with his opulent baritone, he provided the most arresting portrayal on the whole night. His voice always had a calm and collected demeanor with a roundness that resonated fully in the Met’s auditorium. Papageno’s vocal line, while melodic, is highly rhythmic and Oliemans managed clarity of sound and diction with great precision, especially with his entrance “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja.”

He also managed solid tonal shifts, none more present than the second Act’s attempted suicide where Papageno goes from singing his jolly tune to then preparing for death, lamenting his fortunes, and then suddenly being saved. The bright and comic tone grew more and more desperate until, with all hope seemingly lost (save for that child that shouted at him from the audience after “eins”), delivered a pained “Nun wohlan! Es bleibt dabei!,” his singing weeping with each descending phrase. When he shifted back toward the bright joy of newfound love, the effect was all the more powerful.

In spoken sections, he was king, coming through with tonal clarity in every moment that added to the humor. When he finally meets Papagena and is drifted off, nothing was more hilariously painful than his prolonged and held-out cry of “Papagena” as he’s carried out of the hall. And his physicality, aloof, but nervy really added to the grounding of his character, which was the basis of so much humor and our connection to him. When he spots Monostatos attempting to assault Pamina for the first time, the fearful interplay between the two was nothing if not hilarious. Ditto for that first interaction with Pamina and his hesitancy to come near her, which played up his awkwardness. His buzzing energy during the initial trial of silence was a perfect foil to Brownlee’s more reserved and concentrated poise.

But the humor wasn’t just about physicality, a device a lot of performers often rely on for comedic effect. There were some moments that relied solely on physical humor that really worked (the entire scene with the bottles and engagement with the audience), but he didn’t use it as a crutch. There was a precision in how he chose to emphasize those moments and when to rely on the delivery of the text or context to deliver the goods. He wasn’t chewing scenery or trying to be a scene stealer; he was constantly working in consort with his scene partners (or in his solo scene, the audience members), creating a glorious equilibrium that allowed the magic of the production to flow. Pacing in opera is so challenging, especially in this one where the second Act (as is the case with “Don Giovanni”) gets drowned down in waiting for something to happen. This is so true for characters like Papageno who have nowhere to go after a while. His big scene prior to meeting Papagena is a literal showstopper, cut off from the main plot and with no seeming direction. But when the actor on hand has such an innate sense of timing, knowing when to take his time and when to step away, as is the case with Oliemans, the result is thrilling and engaging. And this particular moment, where Papageno is literally all alone, might have been one of the most memorable of the entire night. The audience simply couldn’t stop laughing.

Karen Almond

Beautifully Matched Lovers

With Papageno often everyone’s favorite character, the two central heroes often get the shaft in most productions. And let’s be fair, where Papageno is self-aware and grounded, the love story is more archetypal in its character construction. Tamino is the noble prince who must be made wise to be king and Pamina is the damsel-in-distress. But this production and its performers, managed to give this couple more depth. With Pamina, it’s clear she’s a fighter from the start of the opera. She’s dressed in white with a blue track pants and white sneakers, and she’s not afraid to fight back against Monostatos. In Erin Morley’s hands and vice, there’s an unbridled passion from the off coupled with delicacy. Her initial interactions with Papageno were forceful enough to get him to help unstrap her; but she takes care of the rest of the restraints on her own. During “Schnelle Füße, rascher Mut,” Morley and Oliemans managed a solid vocal balance that exhibited their flexibility and joy.

But that confidence is slowly stripped from her. There’s fear in her meeting with her mother where the spunk from her initial scenes is neutralized and she’s physically cornered for most of the scene. Same for her meeting with Sarastro, where she’s often relegated to the same spot on stage, not allowed to move as freely as he is. And then of, course she gets shut down by her very own Tamino.

The standout moment is the famed “Ach! Ich fühl’s” where Morley reminded the listener of why she is one of the best singers in the world right now. The aria opened with a passionate but gentle plea, the agony of heartbreak felt in the soft high notes. This soft approach opened up slowly with the sixteen and thirty-second note runs on “Herzen mehr zurück!” “Sieh Tamino!” was thus more focused and potent in its delivery, Morley’s singing taking on greater desperation. And then, suddenly after following him about the stage, trying to connect with him, it almost as if it Morley’s Pamina gave up, her sound and singing growing softer and more intimate, the high B flat on “der Lieben Sehen” among the most gentle notes she sang on the night. She was no longer singing for Tamino but for herself. With each passing and softening phrase, she drew the audience into her increased physical stillness; the brusque crashing sound from the production was the lone blemish on this most intimate of moments; fortunately, it happened during one of the vocal rests.

Contrast the quiet desperation of that aria with the suicide attempt a few scenes later where Morley’s voice just rang out with abandon as she prepared to use her mother’s knife to kill herself. Here we saw the same fear that the character experienced when tasked by her mother to murder Sarastro as well as when she tries and fails to carry it out. The suicide attempt here might come off a bit awkward in other productions, especially because Papageno also attempts to do the same and the tones of the two feel quite in conflict with one another. But the production’s development of Pamina, from self-secure to increasingly conflicted and confused by both sides of the battle, allows for this moment to be more than just one of heartbreak – it’s also one born out of being literally torn apart by the world around her. And Morley’s vocal intensity here, arguably at its most fierce, matched that in spades.

To conclude her arc, she gets to work alongside Tamino to overcome the trials, allow her to complete the hero’s arc as well. Her “Tamino mein!” featured a luxurious piannisimo that made that brief opening moment feel suspended in time; ditto for tenor Lawrence Brownlee’s corresponding Pamina mein.”

Brownlee’s Tamino also goes through a similar confusion, though his arc takes a different direction. As a prince in a foreign and unknown land, Tamino here is definitely portrayed as a man who doesn’t know where he belongs; he enters with a purple running suit as if he were from modern-day NYC, gets stripped down to white undergarments and then ports a guerilla costume and a gun, before being stripped again and changed into something more neutral.

Brownlee’s initial physicality, always looking around lost, definitely exhibited this feeling of displacement. When he puts on the military suit, he looks like he’s trying to play the part, holding the gun clumsily (and dangerously) in his hands; it feels like he doesn’t know what to do with any of it, but he’ll try as hard as he can. But as the story develops and he finds himself more at home with the challenges Sarastro puts before him, there was greater poise and firmness in Brownlee’s demeanor. You could sense the confidence that had been lacking early on, the hero being born.

And through this, Brownlee’s singing retained a firmness that showcased his potential to be the hero. A lot of the early music for Tamino is placed in the passagio, with some ascensions to G5 and Ab5 that can be quite uncomfortable for any tenor. Brownlee pulled off that initial passage potently; interestingly he kept his voice in this higher register during much of the ensuing conversation with Papageno and the three ladies, allowing him greater comfort for the big aria “Dies Bildnis,” which famously (or infamously) starts with a perilous sixth lead Bb to G natural before hanging high and then even going rather low at one point from a G5 to an F4. A lot of tenors also take this one with ease and delicacy, allowing themselves to warm up into the evening. Brownlee displayed vocal poise throughout, allowing his bright tenor to shine without any restraint or trepidation. The phrasing here felt sustained and the tempo even a bit slower, but one could feel in Brownlee’s singing that his Tamino was savoring this moment of love at first sight.

In contrast, there was a warmer and more flexible phrasing in “Wie stark ist nich dein Zauberton” during which Brownlee matched the tenderness of Morris’ playing. But he also imbued strength in his singing as his thoughts went to Pamina in the middle of the aria, ascending to an astonishing potent A5 at “vieleicht.” The ending of this passage was delivered with the most muscular singing that Brownlee delivered on the night.

This forcefulness was present in other scenes, particularly in his initial confrontation with the Speaker, before his vocal demeanor turned more relaxed and restrained, echoing the character’s own evolution. The big ensemble that follows “Tamino mein!” featured Brownlee at his bel canto best with fluid lines that soared with the ensemble.

What’s beautiful about this production is that when Pamino and Tamina come together, it’s like two magnetics unity polar opposites. Three times they walk across the stage to embrace one another. The first time, it takes the power of the entire chorus to separate them. But the second time, even they can’t break them apart, so at the end of the opera, they circle around them in one of the most sublime visual pictures created on the Met stage this season. That level of magnetism is the result of Brownlee and Morley’s vital connection to one another throughout, their voices perfectly matched when asked to join together.

Karen Almond

Polar Extremes More Similar Than They Realize

And that brings us to the polarizing figures of the Queen of the Night and Sarastro.

Kathryn Lewek has become the Met Opera’s go-to Queen of the Night. Of her 44 performances at the Met to date, all of them have been in this role. And while it is easy to play this “villain” in one dimension, Lewek always seems to find shades and colors to explore. This is perhaps her most inspired turn to date. “O zittre nicht” was sung like a plea, full of sorrow and melancholy. Leaning into the Queen’s own frailty, you could feel the weight of the character in Lewek’s tender legato lines. Often, this is framed as a piece of trickery, the Queen emotionally manipulating Tamino into her bidding. But that wasn’t the case here with Lewek using the high-flying coloratura and the ascension up to that high F to express the pain and heartbreak the Queen is feeling. The final “auf ewig dein” were delivered with full throttle, furthering this emotional toll and coalescing beautifully with Lewek’s Queen collapsing into her wheelchair, completely spent. You can’t help but empathize for the Queen here, furthering the emotional conflict that you feel throughout.

And that was furthered in the second Act during her big scene with Pamina. Lewek’s approach here was full on aggressive and furious as she instructed her daughter to take the knife and kill Sarastro. This aria is often played for its fury and anger to thrilling effect. And Lewek incorporated that here, but she went even deeper. With the Queen repeatedly attempting to get up from her wheelchair, you could feel an internal tug-of-war between a woman trying to establish her power and control, but also feeling too weak and exhausted to continue fighting, the hope almost dashed out of her – if her daughter, her only hope, can’t save her, then it’s clear that she’s done for. And the resulting rage, frustration, and agony of all this could be felt in Lewek’s singing. This might be classical music and “proper Mozartian style” might call for restraint and certain polish, but it is also opera. And opera is always about messy human emotion. As such, there was something raw and primal about Lewek’s approach here to the aria, her voice weaponized with a razor’s edge as she threw off the high notes; it wasn’t always clean and not all the infamous high Fs came off spotless, but it was exciting and potent. There was aggressive accenting in the singing, but there was also a full-throated intensity in how she delivered those final lines “Hört, Rachegötter, hört der Mutter Schwur!” as if it hurt her to think it, much less sing it. The Queen of the Night thus became less a villain and more a tragic hero using her final card in a battle she knows she may never win. There was no surprise that the audience serenaded her with the longest ovation of the night. It was much deserved.

Contrast that full-on emotional power with the more reserved Sarastro exhibited by Stephen Milling. Towering over everyone on stage (literally), his bass boomed into the halls of the Met with authority but always with a sense of reserve. It gave his character strength, but also a sense of mystery, that matched his similarly regal physicality. His elegance and poise was reflected in his two big arias “Isis und Isiris” and “In diesen heil’gen Hallen.” In both arias, Mozart pushes the bass to the limits, forcing him to sing in the lowest reaches of his range. Like the Queen of the Night with her high F naturals, both arias push the bass to low Fs as well, with “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” hanging out in the lower reaches for a reprisal of the main melody. A lot of basses either grunt out these lower notes, or are forced to sing these lower passages softer to accommodate the technical difficulty; but Milling didn’t seem at all daunted by them and managed a seamless transition to those lower reaches without obstructing the balance or fluidity of his line. This vocal prowess allowed the listener to just settle in comfortably to his gentle singing without the distraction that comes with struggling singers. It also furthered that authoritative characterization of his Sarastro.

That made the few moments where he betrayed emotional confusion so thrilling. When Pamina comes at him with the knife, he’s cool and collected. But as he recognizes the Queen’s “darkness” in himself, he shifted away from Pamina’s gaze, shielding himself from her, confused at his sudden sense of weakness. As he punished Monostatos in front of everyone, he looked menacing and tyrannical. Ditto during the Act two conference during which his entourage must decide to allow Tamino a chance at membership. As staged, the decision is put to a vote, but not everyone complies immediately. Instead, the interspersed wind cues service as different rounds of the vote with Sarastro staring down the dissenters. His stern gaze gave him power, but the dissenters quick compliance offered up unique questions about his leadership (the audience laugher certainly colors this moment in different ways).

Among the supporting cast members, the trio of Alexandria Shiner, Olivia Vote and Tamara Mumford were fantastic as the Three Ladies. Allowed greater freedom in crafting the characters, we could feel their passion, their aggression, even their fear throughout their initial encounter with the sleeping Tamino. Always playing off one another, they brought different colors and rawness and at different moments, each singer was allowed to stand out amongst the trio.

As Monastatos, Brenton Ryan played up the lechery of his character, contrasting it with a gentle but polished tenor that, in the context of Brownlee’s brighter sound and Errin Duane Brooks’ more muscular tenor, emphasized his characters’ weakness. Nonetheless, as the man who can’t stop failing, he delivered some hilarious moments, especially when under the spell of the Glockenspiel.

Deven Agge, Julian Knopf, and Luka Zylik were fantastic as the three boys. Their voices nicely coalesced with one another, always together both musically, and especially physically as they strutted around the stage with their canes, their right hands always on their hips.

Richard Bernstein and Errin Duane Brooks were excellent as the Priests and the Armed Men, both delivering muscular musical portrayals that stood out from amidst the cast; they also found a nice balance when singing together.

Finally, Ashley Emerson was fantastic as Papagena, matching Oliemans’ tonal approach perfectly in their scene together; the chemistry was palpable and the fun and catharsis their reunion emitted from the audience was one of the most memorable moments of the entire night.

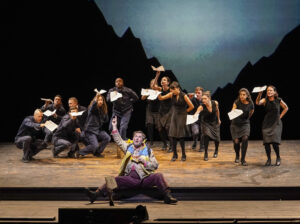

Props to all the actors working on stage alongside the singers, taking on a wide range of roles throughout the night, including giving life to the paper birds or being part of the two warring factions. These performers include Jessica Angleskhan, Jordan Bellow, Antuan Byers, Julia Cavagna, James Dunn, Réka Echerer, Marty Keiser, Jonothon Lyons, Tina Mitchell, Dina Rose Rivera, Natalie Saibel, and Stephan Varnier.

And, of course, the Met Chorus, who was in fine form all night in a myriad of roles.

Karen Almond

Finding the Balance

As she did with “Don Giovanni” a few weeks back, Nathalie Stutzmann delivered another tremendous performance from the pit. Pacing in opera is often the responsibility of the conductor, but a Singspiel is another animal altogether with the spoken dialogue often setting the pace more than the musical numbers do. Even so, when that music comes in, the conductor has to know how to integrate it fluidly into the action. And that’s what Stutzmann does so well.

The overture had a rather relaxed tempo, neither going to slow in its opening or too fast in the more energetic sections, but giving off a propulsive and joyful vibe that played perfectly into the fun that Haberman was having with the chalkboard drawings. And tempi on the whole fluctuated to enable individual performers their space to craft character through music. She wasn’t afraid to operate on extremes; you could feel it in the contrasts between Sarastro and the Queen – the orchestra aggressive and abrasive in “Der Holle Rache” and gentle and sweet in “In diese heil’gen Hallen.” This allowed the overall architecture of Mozart’s music to come to the fore. The children’s appearances were often marked by more relaxed tempi, allowing those scenes to take on a more charming quality.

But personally, the standout for me was “Der, welcher wandert diese Straße” which can often come across as overly emphatic. One understands the tendency to dig into the seriousness of the passage (it literally starts with the text “The one who walks this road full of grievances”) and the fact that its musical accompaniment is the most academic of all musical forms – the fugue. But there was lightness in the orchestral playing that allowed not only the structural complexity to come through with clarity, but also gave it momentum and grace that is often lacking in favor of monumentality.

And all of this, while managing the greatest challenge of all – balance in sound. With the orchestra raised almost to stage level, it is easy to overpower singers. Stutzmann, despite her unfortunate comment to The New York Times, managed this extremely well with perhaps only one moment of imbalance; this lone blemish was Sarastros “Iris und Osiris,” but it had more to do with the placement of bass Stephen Milling all the way upstage during the scene. When Milling came downstage, his sound came through with much greater clarity.

Props must be given to Morris on flute and Wagorn on glockenspiel; both performed tremendously in their respective roles as the instrumentalists on stage and in the pit. Wagorn in particular got the best laughs, particularly with his pairing alongside Papageno; I won’t ruin one of his entrances that got one of the biggest laughs of the night.

I am not going to lie – the 2022-23 season has featured the most consistent lineup of new productions that the Met has to offer. From a solid “Medea” and “The Hours,” to a triumphant and revelatory pair of Mozart operas, the quality seemed to improve with the unspooling of new productions. I’ll repeat what I said at the start of this article – with its top-notch cast, its humanity, its celebration of the magic of stagecraft both new and old, and it’s celebration of the power of music it’s the greatest production that Met Opera has brought in years.