Metropolitan Opera 2021-22 Review: Akhnaten

Anthony Roth Costanzo & Zachary James Lead Fantastic Revival of Glass Masterwork

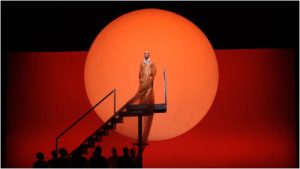

By Jennifer Pyron(Photo Credit: Ken Howard / Met Opera)

Opera is a way in which we can creatively examine momentous historical shifts and rediscover the possibilities of radical change in an existentially emblematic and exuberant way, especially at the Met.

However, what is it that makes this art form balanced enough not to tip over into becoming purposefully deceptive and overly politically charged? More specifically, is it possible to portray the life of an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, whose enigmatic history was deliberately destroyed by his successors, in a way that evokes the core of a spirit’s essence and does not become lost in the overreaching of storytelling?

Take a moment to imagine living under the rule of an Egyptian pharaoh named Amenhotep IV, known as Akhnaten, “spirit of Aten,” who worshiped the sun disk. Impacted by a hierarchy of elite dominism that was their designated form of worship, you were instructed to do the same. How do you think you would feel if you were expected to follow the destruction of your only known religion, polytheism, in order to take on what can only be considered as a ceremony? The riches and opulence they fed themselves like a hungry machine to keep up with the expectations of their own rule slowly giving way to the eventual loss of your own freedom. Your birthright as an individual to enlightenment being taken in order to be ruled by only one way, Atenism.

On the other hand, take a moment to imagine living under the rule of a new leader that did not fit the mold of your former dominating rulers because of how he perceived reality due to his spiritual awakening and therefore wanted to share new ways with you about how to experience life as a way of ceremonial worship. Through his reign you were freed from giving your power away to multiple gods. You witnessed self-sovereignty in harmony with the sun as source, but how could you relate to this level of radicalism yourself? At what point were you convinced that Atenism was for the good of all? Better life? Ceremonial death? Promise of glorious afterlife? How is religion today any different from this point of questioning?

Unfortunately, we have no real way of knowing the truth about what exactly took place during Akhnaten’s rule. This is why asking every question serves us best in order to learn fully from the spectrum of his ways as pharaoh and the possibilities from the past that we use to build our present foundation of knowledge. Exacting our excavation and handing everything over to a creative process along the way. This is the gift of being an artist and, in my opinion, there is only one specialist in this craft of careful consideration who could write ‘Akhnaten’ in this methodical way.

Philip Glass

In 1983, Glass wrote “Akhnaten” as the final installment of his Portrait Trilogy which also includes “Einstein on the Beach” and “Satyagraha.” His work is an ever evolving prolific progeny of purposeful portrayal. An otherworldly summoning of spiritual presence. Glass’ team of collaborators for “Akhnaten” assisted him in pushing the boundaries of language and encompassing a new rite of passage for translating an extraordinarily ancient atmosphere. The methods to his conceptual madness did not stop there though. Underlying throughout his score, Glass denotes a pulse. This singular pulse weaves in between the tempos and all the beautiful music but cannot be defined based on musical tradition or even one’s ability to academically contrive in understanding. For, this is the pulse of Akhnaten’s spirit. The frequency of a searing light solely devoted to worshipping Aten, the sun disk. Super consciousness in musical form.

During the debut of “Akhnaten,” Anthony Roth Costanzo did several interviews and talks about his role. He answered many important questions pertaining to the complexities of the score, methods of acting that worked best when memorizing and how he felt drawn to this role in a deeper way. The one question he has yet to answer though is about whether or not Akhnaten was for the good or evil of all that was during his rule. Costanzo uses this internal processing in every single performance as a way to usher forward this unsettling unknowing. He creates an anecdote for the emptiness that is within every existence. The sure sign of a pure artist.

Anthony Roth Costanzo becomes Akhnaten entirely through his presence and I personally cannot imagine anyone ever doing this level of performance while in this role. His gift for giving himself over to the art in which he is creating, moment to moment, is vitally refreshing and inexplicably humbling. There were many times during his performance where the audience was completely still. Absolutley silent. Nothing could compete with the power of Costanzo’s being in every sense of the term. The way he creates space around him and through him from start to finish is a revelation. He is the Philip Glass interpreter of our time. He is the right now that must be experienced as Akhnaten.

Throughout the progression of the opera there were costume changes that showed Akhnaten’s full body and the growth of his breasts. I must mention this because it is deeply emblematic of the spiritual progression of his own transformational beliefs. The feminine and masculine energies merging as one to empower his presence and emphasize his individuality must be made aware in hopes of a new way in which we can all move forward together. Understanding that which makes these costume changes shockingly different is not meant to be in the hands of a critic but rather, in the hearts of every human being trying to understand more about being human. Anthony Roth Costanzo’s entire career is founded on this very important lesson. Learning how to be is the only learning that must be done.

The Sun of A New Dawn

The Funeral of Amenhotep III, in Act one, reveals both a corpse and a ghostly figure, performed by bass-baritone Zachary James. Despite the end of Amenhotep III’s reign, Zachary James as Amenhotep’s ghost continues throughout the opera to be a highly charged figure of powerful presence in favor by the gods. His voice is electric in its ability to transfer through the orchestra and off the walls of the Met’s hall. Every moment is like a lightening strike transmuting along its path. He signifies the most momentous shifts in this opera and voices the weighted burden of Akhnaten’s short-lived and brazen rule. A light snuffed out too soon.

Meanwhile, Dísella Lárusdóttir, in the role of Queen Tye, brought a vital and holistic feminine intelligence to her performance. Her soprano voice glistened in brilliancy above the heavy undertow of violas, cellos, double basses and lower voices.

Rihab Chaieb, as Nefertiti, displayed a different approach in her performance. She is portrayed to be in devotion to Akhnaten in this opera, and therefore at the hands of his will. Chaieb’s voice in Act two, when both Akhnaten and Nefertiti affirm their love for each other, mirrored the purity of Anthony Roth Costanzo’s voice. The two become one in this moment. There is nothing left to keep one from wanting anything less than the whole of all that is.

Finally, conductor Karen Kamensek led the entire production through her precision in care. She is the backbone of this opera machine and her innate ability to direct the entirety of “Akhnaten” was masterful. Kamensek is grace personified as a conductor and whole heartedly inspires all.

On the whole, this is exactly what the Metropolitan Opera needs to do with modern operas. Champion them and then revive them at a quality that matches or even exceeds the first go-around. This was a perfect encapsulation of how powerful new opera can be and its importance to the continued growth and evolution of the art form.