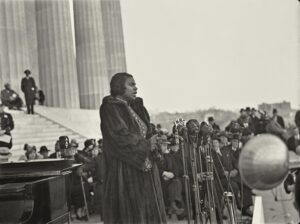

On This Day: Marian Anderson and Her 1939 Lincoln Memorial Performance

By John VandevertOn February 27th, 1897 African-American contralto Marian Anderson was born in Philadelphia. With a career full of monumental firsts and acts of heroism, Anderson’s name is forever tied towards the fight for equal rights, not only for women but for the African-American community. A beacon of social change, Anderson’s legacy will never be forgotten.

As an activist performer, Anderson accomplished a great deal. She was the first African-American to be featured at the Metropolitan Opera House (singing Ulrica in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera in 1955), worked on behalf of the United States government and the United Nations, and was an integral figure in the 1960s civil rights movement. Among her crowning achievements, however, was her participation in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, appearing alongside African-American singers such as Mahalia Jackson, Camilla Williams, and even American guitar singer and activist Joan Baez. But earlier, Anderson had been a central figure in an event far more controversial. In this post, we’ll explore Anderson’s denied (and then relocated) performance at the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) Constitution Hall in Washington D.C. Blocked from performing, on April 9, 1939, after tremendous national backlash and widespread protest, Marian Anderson was finally welcomed with open arms at the Lincoln Memorial.

For some context, Constitution Hall had a strict “only white” policy which, despite Anderson’s popularity, was not going to be loosened. Anderson’s 1936 tour had included a stop at the Hall but was blocked. The years leading up to 1939 were a difficult but strangely fruitful time for Anderson. While her career and power grew, she began insisting that if a crowd was to be segregated it had to be down the middle rather than sequestering African-Americans to the back as was the standard approach. Flash to 1939 and Anderson’s manager Sol Hurok wanted to again include the Hall in her tour. Hurok fought for Anderson’s appearance at the hall, working with The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Howard University (one of the first institutions for African-American education). However, Sarah Corbin Robert (then President of DAR) unequivocally banned her on the basis of her race. The resulting backlash against this decision has filled many history books but it’s enough to say that no one was going to take this lying down.

At first, Teddy and Eleonora Roosevelt (President and First Lady of America, 1901-1909) didn’t do anything after being reached out for help. Unsure of what the politically correct action was, eventually Eleonora spoke up. She turned in her resignation as a member of DAR and quickly published what has become one of the most potent examples of what constructive change looks like. On Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, accompanied by long-time friend and colleague Finnish pianist Kosti Vehanen, Anderson sang for a crowd of over 75,000 people. At the end of the concert, having taken the audience for an emotional journey, Anderson is quoted as having said:

“I am so overwhelmed, I just can’t talk. I can’t tell you what you have done for me today. I thank you from the bottom of my heart.”