Fresco Opera Theatre’s ‘Clara’ and The Misunderstood Love Triangle

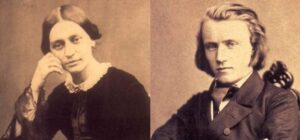

By John VandevertThe story of Clara Josephine Wieck-Schumann and Johannes Brahms is one of both fact and myth. Through their forty years of correspondence, they expressed adoration for each other and the art of music itself. Yet, do we really know what their love was like? Fresco Opera Theatre in Wisconsin had created an opera called “Clara” to explore this relationship using the music of Clara, Brahms, and Robert.

A central theme of the opera was the tenuous balance between Clara’s decision to pursue her career, her tough marriage to Robert Schumann, and her relationship with budding Romanticist Johannes Brahms. Premiered during the first week of April in 2016 in Madison, Wisconsin, the work was a composite of many different pieces by the three composers, some of which had never before been heard performed together.

To explore the relationship from a historical perspective, I sat down with Clara expert Sarah Fritz where we discussed several topics related to the relationship. Thanks to the research and arrangement by Dr. Melanie Cain, the opera featured a balance of well-known and lesser-known songs and instrumental works by the three, but among them one stood out.

Clara’s ‘Lorelei’

Clara’s 1843 song “Lorelei” is considered to be one of her most dramatic works due to its repetitious musical texture and fast-paced tempo, echoing Franz Schubert’s 1815 art song “Erlkönig.” “Lorelei” was created as a birthday gift to Robert, not an unusual thing for her to do. As Sarah noted, “she gave the song to Robert for his birthday. He loved getting her compositions, but for him, his composing came first. He did write that he regretted her ideas didn’t get worked out.” The impetus for Clara’s first songs was thanks to Robert’s encouragement. As Sarah shared, “he wanted her to write songs, so he handed her a few poems and invited her to do a joint opus (Clara’s 12th and Robert’s 37th). She caught the bug and kept going.” Context, however, is key towards understanding this piece. Sarah noted that, “after she got married, her diaries became something that her husband would read.”

We can only speculate about what Clara was really trying to say in this song but it is clear that something was on her mind. Sarah continued, “we don’t know what her thoughts were.” Another fascinating point is that Clara was never allowed to play piano if Robert was home, as it would disturb him. Sarah shared more detail on this noting, “up until the second to last year of her marriage, she wasn’t allowed to play when Robert was composing. The only time she could was on the evenings when she went to the pub.” Nevertheless, Clara continued composing. As Sarah expressed, “clearly, there was something in her that wanted to compose. She could have quit.” More interesting, perhaps, is the fact that it was left out of an opus and stands on its own. Sarah shared more on this when she said,

“She published a bunch of songs around the time, but this song didn’t make it into her Op. 13. We can only guess why. I think it was because it was too masculine for a woman. It doesn’t sound like a ‘woman’ wrote it.”

Clara & Brahms’ Relationship

Perhaps one of the most misunderstood relationships in music history, the love between Robert Schumann, Clara Wieck, and Johannes Brahms, was not so much about human love but divine love through music. As Sarah noted, “in terms of physical attraction, we actually don’t know. There was love words exchanged, ‘I love him like a son’ [Clara Schumann]. But Johannes, fourteen years younger than Clara, also wrote that he loved Robert, and Clara wrote that Robert also loved Johannes.” We know that the three became acquainted with each other in 1853 after Robert took Brahms under his wing as a student due to his rising talent. By 1855, the relationship had grown considerably, although inseparable from their adoration for each other’s work. Sarah noted emphatically, “it was the music. She was super famous [as a pianist] when he was 20. It’s hard to imagine how starstruck he was by her.” As Brahms grew in fame towards the end of the 19th-century, Clara celebrated his growing popularity.

But at the heart of their relationship was music over everything. Sarah confirmed this when she said, “for them, music was everything. It was their whole lives. It wasn’t just their careers but their lives and voice.” Between Brahms and Clara was a love that was not limited by words nor the physical level but something far greater. Sarah commented that “they loved the person through the music and the music through the person.” Although not a physical relationship, their attraction to each other superseded the barriers of the material plane. Their method of communication was music. Brahms and Clara represented a different shade of German Romanticism, quickly fading with the rise of Wagner and Liszt. Sarah noted as such, “Wagner and Liszt were in one camp and they were in the other. Brahms felt alone because all the young composers at the time were following them and Clara felt alone because Mendelssohn and Robert had died.” They escaped through their music. As Sarah stated,

‘They weren’t talkers. We think of them as talkers because of their letters but when together, I think there was very little talking and just music.”

Clara’s Reputation

One of the more contentious elements of our discussion was the lasting reputation of Clara. Not only Clara the pianist but more importantly, Clara the composer. By Clara’s death in 1896, the musical world was a very different place than it had been during the 1850s. In 1856, Clara had stopped composing after the death of Robert, although the plight of a woman composer during this period was nothing short of constant battles and Sisyphean power struggles with a predominately all-male establishment everywhere one looked.

However, Clara’s reputation as a pianist was a thing of epic proportion, spanning continents and continuing until the mid-20th century, when the last of her students and original audiences had passed away. As Sarah explained, the choice to stop composing was a voluntary, albeit painful, one. In her words, “she stopped, voluntarily, performing his works before Robert died. After that, she would perform them if people asked for them.” She went on to say that her students would play her pieces but essentially she had no lasting legacy as a composer then, “she wasn’t forgotten as a composer, but for women composers back then, it was bad.” As a performer, she was nothing less than artistic royalty. Sarah expressed as much, “she was Queen of the piano, and considered the great Clara Schumann as a performer and artist. She had no reputation as a composer but as a performer was world-class.”

After Clara’s death, her memory lingered for a bit before eventually dying out, only to be rediscovered at the end of the 20th-century, thanks to the musicological alignment with second-way feminism, known as “New Musicology.” But during the first-part of the 20th-century, Clara’s name was still a sacred word. Sarah’s words were profound, “during the first-part of the 20th century, people were still alive who remembered hearing her play. It was only after they had died that her started getting pushed under the rug.” When we think of now, Clara’s memory and compositions are slowly but surely being played and recorded by some of the world’s best orchestras and most prestigious labels.

Clara’s 200th anniversary, occurring in 2019, was a spectacular and internationally recognized event. As UNESCO recognized her as “one of the few women able to make a living from music at a time when the music industry was already a male-dominated job.” On the subject, Sarah noted that many women were able to make a living as piano and voice teachers. In a later comment, she noted “more accurately, Clara was one of few women pianists to reach international superstardom and have a performing career that lasted into her sixties.”

During our conversation, Sarah shared more on the celebrations. “In Germany, they did a good job with Clara’s 200th anniversary. There were a lot of concerts there and in the United Kingdom. It did springboard some projects as well.” Again, despite the successes that the anniversary brought, including a DECCA recording played by Isata Kanneh-Mason, there has been little traction towards integrating her work into the repertoire in universities and conservatories. As Sarah shared, “the majority of piano teachers and professors have never taught a work of hers. Her music has no complete publication yet.”

But Sarah, and those who love Clara’s music, such as I, have not lost hope. With a confidence much like Clara’s, Sarah expressed that her goal of seeing Clara’s work becoming regular concert repertoire and situated among the greats, although not yet complete, remains her life goal. In stalwart confidence she said,

“I won’t breathe a sigh of relief until her work is programmed again in five years, so she becomes part of regular repertoire for orchestras and piano professors. That’s a long way off.”

Categories

Special Features