Hungarian State Opera 2018 Tour Review: Mario and the Magician & Bluebeard’s Castle

Eccentric Double Bill Offers Electrifying Social Commentary

By Logan MartellAs the Hungarian State Opera continues its New York tour at Lincoln Center, the second night saw a double feature of performances from Hungarian composers: “Mario and the Magician” by Janos Vajda, and “Bluebeard’s Castle” by Bela Bartok. What followed was an enthralling showcase of the talents of the company, wherein the artists powerfully brought to life the methods, and madness, of the directors and crew.

The first of the one-act operas was Janos Vajda’s “Mario and the Magician.” First making its premiere in 1988, the opera has quickly grown in popularity among Hungarian audiences and has enjoyed a number of productions and revivals since.

The Elephant in the Room

For this tour, the company brought Peter Galambos production which for the most part worked but one bizarre aspect of this production came in the costume designs by Eniko Karpati. The villagers and royalty, all gathered to see a performance from a famed magician, were dressed as a myriad of characters from pop culture; in attendance was The Joker, from “Batman,” C3P0 and Luke Skywalker from “Star Wars,” Marge and Bart from “The Simpsons,” alien Roger Smith from “American Dad!,” Kenny from “South Park,” Beatrix Kiddo from “Kill Bill,” and many more. While glaring at two ostensible Coneheads, I soon realized trying to identify each member of the crowd became a distracting task that did not provide any additional meaning to the story.

A Beckoning Bass

Quickly at the head of this confusing congregation was the magician Cipolla, played by mesmerizing bass Andras Palerdi. With his flowing robes, long hair and beard, and air of mystique, the design of Palerdi’s Cipolla created a resemblance to the historical ribald moujik, Grigori Rasputin; a connection made all the more tangible by Cipolla’s overwhelming power of suggestion and hypnosis. The earlier parts of the opera featured a number of exchanges between Cipolla and the crowd of characters, wherein which a feat from the magician would send them into a burst of musical squabble before Palerdi’s seizing bass would silence them and, joined by more legato phrasing, would begin to work his spell again. Examples of this included a challenge from the crowd to solve complex arithmetic in his mind, and to find a hidden rose after being blindfolded; this later challenge featured an extended slow rise in the orchestra which heightened the anticipation leading to the reveal of the rose.

Though this opera is originally set in Torre di Venere, Italy, the modern staging did have some positive aspects. After hypnotizing an older woman and putting her under his power, Cipolla has her reveal her past to the crowd while holding a microphone to her face. This not only audibly highlights her sighs and chuckles, emphasizing her mental state, it frames Cipolla as a figure somewhere between a talk show host and a televangelist, seeking to probe into minds and souls alike. Sure enough, the crowd becomes eager to line up to receive Cipolla’s healing touch, leading to an ecstatic chorus number as many of them, after receiving the touch, broke into convulsions before rising to dance. When Kenny from “South Park” was touched part of me expected him to meet with the sort of sudden, senseless death his character is known for. Instead, this frantic bout of faith healing ends with a sudden climax in the orchestra, as an unseen force brings all but two characters to the ground: Cipolla, and a young man named Mario.

The Power of Silence

In the non-singing role of Mario was Hungarian actor Balazs Csemy. His concise dialogue provided a stark contrast to Cipolla’s crooning phrases and gave the sense of a character not willing to play the magician’s game. This defiance even saw Csemy walk out from behind the transparent curtain to the front of the stage, leaving the other characters in their separate, boxed-in world. Here, the crowd of characters finally seemed to make their purpose clear; their presence within the box established it as a kind of television set for Mario to temporarily escape from. Ultimately, Mario is coerced back and Cipolla is able to have him divulge the secrets of his heart; namely, an unrequited love named Silvestra. Transgressing Mario’s boundaries even further, Cipolla dons a mask made from the picture of a woman whose face I did not recognize if it was meant to have any connection; the magician then draws Mario into a kiss before undoing his hypnosis and making him the laughing stock of the gathering.

As per the libretto, an enraged Mario pulls out a gun and shoots Cipolla, presumably killing him. This production, however, had one final trick to play. Cipolla rises and unrobes himself, revealing a bulletproof vest as Mario is apprehended by security, and the crowd of characters burst into a chorus singing “Salve!” while thrusting their hands into the air. This last laugh strongly suggested the passions and cares of one’s life to be something of a grand farce put on display for the eyes of all to watch and ended the first half of the evening on a crazy and comedic note.

Tradition and Terror

Next on the bill was Bela Bartok’s opera “Bluebeard’s Castle.” This was Bartok’s only opera and one that has garnered wide exposure throughout the world. The summary, as per the program, reads: “Bluebeard and his new partner, Judith, get acquainted with each other after arriving in his castle. All of this happens by way of seven symbolic doors leading into the secrets of the human soul. The enigmatic work follows the evolution of the relationship between two people and the different stages of getting to know each other and growing apart refracted allegorically through symbols and meanings.”

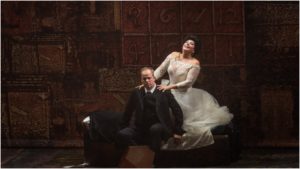

When Bluebeard and Judith arrive, the castle and its many halls, as shown by a projection onto the stage’s backdrop, stretch out ominously. Undeterred, Judith, played by mezzo-soprano Ildiko Komlosi, beamingly affirms her love and commitment to her new husband. Wanting to let sunlight into every room, Judith is warned against opening the seven doors sealed by Bluebeard, and it soon becomes clear that Bluebeard and his dire castle are deeply connected to one another.

Throughout the performance, Komlosi displayed an abundance of vocal power and grace. Outraged and tortured merely by the thought of her husband keeping secrets, she succeeds in opening the first door, leading to a vision of a torture chamber. Though horrified, she persists in her need for revelation, Komlosi soaring at the heights of her voice with the phrase “All the doors must be opened!” After seeing and enduring the fifth door, which reveals the extent of Bluebeard’s lands her little, almost distant, answer of “Your land is lovely and great,” prompted a huge swell from the orchestra, as if Judith has completed her task to her rejoicing husband, although two doors still remained. For all of Judith’s fervent prying, Komlosi’s portrayal made it clear that love was what drove her on despite the growing confirmation of all her worst fears.

As Bluebeard, Andras Palerdi’s portrayal was markedly different than the one he gave as the magician Cipolla. In this work, Palerdi was a compelling mix of defense and invitation; drawing Judith into his castle and world, yet doing his best to keep her out of the seven-sealed doors. Only through love does Judith succeed in forcing him to open up, ironically placing her in greater danger each time. When all the doors are open and the truth regarding Bluebeard’s former wives is revealed, his character takes on a fatalistic resignation and seals Judith away with the others.

His actions, despite the seemingly-genuine love he bore for her, suggest that his seduction and implied murder of these women is brought about by an irresistible force inherent to his character; that the program describes Bluebeard and Judith as archetypal man and woman thrusts forward the pointed claim of woman as being vivifying innocence, and man as being a suffocating lover that destroys as many women as he is able to. A sinister organ featured in the orchestra captured the twisted love and beauty unfolding before Bluebeard returns to how the audience finds him in the beginning: alone, and contemplating grimly on the events of his life; claiming it to now be a night from which the sun will not rise, Bluebeard drifts unaccompanied into a wearied sleep, bringing the opera to a close.

Details from the Director

While both operas of the night went about it differently, the theme of control was at the forefront of the programming. Director Peter Galambos shared an enlightening insight into the concept behind the productions, saying “Both ‘Mario and the Magician’ and ‘Bluebeard’s Castle’ are labyrinth stories. The labyrinth story is a metaphor for initiation: the place where we go in order to reach an understanding with ourselves. ‘Mario’ is all about self-understanding in a social sense, whereas ‘Bluebeard’ is about personal self-knowledge. Every human being has unique abilities, and it is no trivial matter how we use our talents. The question is: what happens when a person believes himself to be a god? What transpires in such a person’s mind, and what consequences doe it have on his environment? The more deeply that people understand their own demons, the more uncertain they become about them. And yet, their curiosity is always stronger than their fears. Facing our demons – no matter how painful this might be – leads to a better understanding of ourselves. I believe that this initiation ceremony is the rite of passage in the process of becoming an adult.

“Today we face a crisis at both the social and personal levels – by and large, and with great respect to the exceptions, we have lost our ability to become adults, by which I mean true recognition of the problem of responsibility on the part of the individual. In the case of ‘Mario,’ the source of the problem is social immaturity, which feeds into the interdependent and mutually complementary relationship of control and obedience, just as Thomas Mann himself wrote.”