Holy Fire: Verdi’s Representation in McQueen’s Spring/Summer 1999 Fashion Show

By John VandevertWe are all familiar with the aphorism ‘clothing maketh the man‘ and its related parabolic lesson, regardless of the superficiality of the statement and its inherent inadequacies as a didactic phrase that can be really listened to in any meaningful way. The backward iniquitous core of this phrase most properly resonates as eternally problematic when reworked in George Bernard Shaw’s feminist parable “Pygmalion.” Here the innocuous cockney protagonist Eliza Doolittle reinvents herself through elocutionary lessons and finer dress. Only after this does Doolittle, a lowly street urchin, improve her external appearances and is finally ‘seen’ and societally recognized as worthy of respect. Such a dynamic change was not self-instigated, however, but brought about by the seditious influence of two male linguistic academics. The story goes on to show that their wanton disregard for Eliza’s psychological wellbeing was fed by their scientific inquiry—more like a hollow bargain of “Can we successfully raise this girl from hellion to duchess?” The novel uncomfortably closes with Eliza confronting her laboratorial enslavement, but with no definite answer to if she rebukes or concedes her station of serf, now having been elevated.

This amorphous conclusion epitomizes the nefariousness of the aforementioned aphorism. If one tailors themselves and their vocabulary to prefabricated morays without first comprising an intuitive sense of self beholden to no one, then what arises is nothing by a fallacious impersonation of naturality and a contrived sense of organicity. This is something that neither the receiver nor creator can be proud or happy to experience. This is a heavily subjective space of creative irresolution where the art form seems to live unharmoniously with its content, where something can have clearly innovative design yet a perplexing execution.

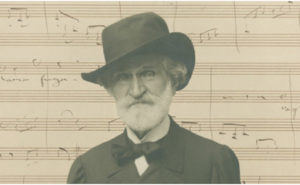

Both music and fashion seem to rest in similarly unstable vibrancy. Take for example a two-minute clip depicting a singular garment from Alexander McQueen’s 1999 Spring/Summer fashion show. The piece is ominously entitled “No.13,” a traditionally unlucky number, and is accompanied in the video by the gnashing supplications of ‘Libera Me’ from the 1967 La Scala performance of Verdi’s ‘Requiem,’ sung by the extraordinary “Mother of Grace,” Leontyne Price. But how does textile manipulation, a visible medium whose creative idee fixe straddles utility and exorbitance, connect and interact with sound manipulation; the notorious societal underminer and invisible swindler of rationality? Cut from the same fundamental cloth of real-world aesthetics, music, and fashion are ideological portents and societally-derived methods of self-expression. According to the social theorist Jacques Attali, music is “noise given form according to a code”which the listener must decode and valorize, lest the potential input remains static violence, ceaselessly rupturing the equilibrium with faithless evangelism.

Important to note is the sociocultural context: the ‘Why?’ behind the fashion show. As memorable as McQueen’s ‘No.13’ was as a cross-epochal political statement–on the one hand refuting the industry’s typification of the mortal feminine as something superficially vulnerable, on the other inculcating fashion with a visceral, hedonistic patriotism–the show’s greatness comes from its synthesis with another theme. Instead of bending the knee to the unscrupulous industrialization that the fashion industry was suffering from in the late ‘90s and betraying normalization, McQueen chose to purposefully utilize both masculine and feminine materials in distressed states–as well as a model with two prosthetic limbs–in order to eviscerate the harmful trope of what I call “Yes Men fashion.” As recounted by Andrew Bolton, McQueen’s official biographer, the show was replete with allusions to the diametric yet synergistic relationship between utility and leisure, pleasure and pain, celestiality and mortality, birth and death, and even the subtle ‘sublime versus the beautiful.’ Traversing the complex plane between organicism and mechanicals, this show sought to bring to attention the abjectness of humanity’s relationship with beauty and the tragedy of its own beliefs. Inspired by the late 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement–an artistic reformation that aimed to bring the human element back into production and reprioritized human labor and skills–McQueen’s sensational ‘No.13’ was what Scriabin’s ‘Op. 60’ had been, and what Wagner’s Ring Cycle had insinuated. It was a cinematically bound window into the constant, unsympathetically parasitic reality of human and Godly arrogance, and the contemptuous belief that somehow we, the faulty ‘children of God,’ were capable of controlling the natural world.

By using both hard textures–like leather and molded plastics–in surgical and medical ways, fashionably utilitarian footwear giving an “orthopedic look” and evoking the ‘cold intelligence of the machine,’ alongside delicate fabrics like lace, ruffles, and silks which captured the beauty and fragility of nature, the construct of beauty itself was eviscerated and replaced with something greater. It was a sublimity, conceived of through positing the female form and the sensual crudeness therein–some of the garments exposing the nipples and breasts–as the only real paraclete of beauty. This highly orchestrated “fabric opera”–a fashion show with narrative weight–fused two idiosyncratically McQueenian traits: finished maximalism and raw minimalism. This could be considered equivalent to the dichotomy between the classical and romantic periods in music. While the classical was ‘from life to culture,’ the romantic was ‘from culture to life.’ Such inverted linearity reads as immediately McQueenian, and by extension Wagnerian, Verdian, and Scriabinian.

This symphonic theme extended even more minutely, as the location, lighting, and set design carried within them the complex dichotomy between function and fashion and utility and triviality. When it comes to the final dress worn by the iconoclastic ballet dancer and model Shalom Harlow, there is no symbol more indicative of the caustic angst interceded by bourgeois ambivalence and steely, proletarian optimism that was the 2000s Fin-de-Siecle than this simple garment. Nothing but a thick leather belt, muslin, tulle, ‘orthopedic’ kitten heels, and industrial paint comprised the climatic outfit of interest. Its impact has not diminished in the slightest, despite the garment’s exhibitionist lineage.

In a nostalgic remembrance, Harlow draws back the curtain on what now reads as an “Eyes Wide Shut” moment, where the message was too raw to be learned or understood at the time. While recalling the episode, I ask my readers to consider its Verdian adjacency. What can be assumed? McQueen had appropriated two Fiat spraypainters to act as Fasolt/Fafner-like characters who, in their attempts at self-indulgence and hedonistic enrichment, instead get themselves killed in the process. While not entirely analogous, the role the mechanical limbs play is one of the intrepid leaders of techno-supremacy, ready to kill everything and anything out of misplaced fear and vitriolic disgust. As Harlow stepped onto the platform, spinning in gentle circles, she notes how the mechanical arms began to writhe and awaken, sensing a warm-blooded body.

“And as they sort of gained consciousness, they recognized that there was another presence amongst them, and that was myself.” With riotously pragmatic authority these puppets-qua-puppeteers swiftly became the human’s master, reminding us of many oft-discussed global themes: obviously Man vs. Machine, but more challengingly Creator vs. Invention and Son vs. Father. They were built by human hands but now were destroying those same hands. This is a relatively transparent allusion to the post-industrial fears that gave rise to the Arts and Crafts movement.

One must acknowledge the humanity within the utility, the creator within the product before we are consumed by vanity and ignorance which stops our intellect from pondering farther than the surface. As fundamentally methodical, sonorously transcendental, and architecturally sound the Germanic compositional school may be, giving rise to greats such as Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven one is left bereft of something a bit more–dare I say–human. That is the carnal fetor of life that makes being human so exciting, and which Verdi did so brilliantly. As Harlow began spinning in fearful anticipation, the machines continued their awakening. Now they transformed from simple curiosity to active hostility. They had taken control over the embryonic space between silence and cacophony, and the murder plot was set. The dress and its wearer became prisoners of war and victims of an undefinable conflict against intangible people, lacking a definite beginning and end.

Thus, as Harlow became privy to the machine’s motives, nothing could be done but wait. “I started to lose control over my own experience, and they were taking over.” They began to spray industrial bile onto the pristine canvas, sullying the virginal space with monstrous patterning: the same way these mechanical masters would paint a car on the production line. Another allusion to the Man vs. Machine trope arises here. The machines were acting on a plan, an intricate and complicated binary plan comprised of nothing but ones and zeros. As McQueen recollected in 2003, “It was really carefully choreographed. It took a week to program the robots.” So they sprayed and sprayed, until at last, they sprayed no more, having exhausted their internal teleology-qua-individual desire. Harlow then walked forward and surrendered herself, in all her bleeding rawness, to the vociferous press and gawking audience, and then stumbled back, retreating away from public view. Described as an “aggressive sexual experience,” the machine’s “rape” of Harlow’s safety and the dress’s purity was a multi-dimensional allusion to not only the pernicious obstacle of modernism but the inescapable fact that the human’s role as apex predator was quickly coming to a close. Nothing could save us from that fact, not even God. It is not clear what McQueen believed, but it was something similar to Verdi, who, as alluded to later in this article, was considered a secular humanist: forever questioning and forever inquiring.

I must make clear a fact here which will be explored later in the piece: the original music used during this visceral assault on Harlow was derived from Mozart, namely his “Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major.” Pairing “No. 13” with Leontyne Price’s haunting rendition of “Requiem” was an inspired choice made much later by an aspiring individual who uploaded an edited version of Harlow’s encounter with the machines to Youtube.

“No. 23” was used in the mid-1780s for a commissional bid by Prince Fürstenburg of the Austrian city of Donaueschingen. Having returned to Vienna in 1781 after completing his unsuccessful, four-city employment tour, Mozart would write six works, all in A Major, and would then never again revisit the key in his lifetime. Marked for its unique blend of sanguine lyricism, intrepid bravura, psychological ambiguity, and a quintessential methodical thought to its formal construction–something we have all come to associate with the boy Genius–“No.23” stands as a wise choice for McQueen’s ‘No.13.’ Its approach to harnessing the eccentricities of emotive and textural oscillations proved to be popular throughout the ages and is regarded as one of the most played concertos of Mozart’s total 23.

Its classical, ‘from life to culture’-based brilliance is the most striking element, however. I would even dare say it is the element that unifies Verdi, Mozart, and McQueen, one that puts them into a sacro-secular triptych: a multimedia glorification of what it is to be human. The differences, however, come in the execution and the realization of this powerful idea. A passage, explored in-depth later, by the German music historian Hermann Abert reveals that Mozart’s genuine interest lay in how human emotions could be transformed into organized, musical renderings: “Rather did he feel a constant urge to master this raw material of spirit by giving it form.” But I do not write solely about which music scored the original catwalk performance and would go so far as to suggest that the original music should be challenged. Moreover, I believe that it does not matter what music scored Harlow’s harrowing moments in the spotlight, as Mozart and Verdi strove for the same heady jewel. It is this, something that transcends both artforms–music and fashion–and becomes something more, something innately and vitally human, that I write about here.

Under the neo-naturalist, post-realist, and purview of things that were previously conceptually secure has now become epistemologically vandalized. All previously fabricated knowledge objects are now nothing more than “dematerialized data floating in frictionless space.”As rich as this surrealist observation inevitably is, the question remains: how does this relate to the effulgent monstrosity of Verdi’s “Requiem” and, moreover, the aphorism which opened this piece and McQueen’s singular garment? The answer lies somewhere among the warring prophetical factions of the late 19th-century, specifically between the anomic ravishes of the Fin-de-Siecle and the hopeful feistiness of Belle Epoque. More contemporaneously, it lies between the ever-lurching grip of modernity and the sanguine nostalgia of “doctrinaire sentimentalism.”

Chastised for its garish immodesty, “deplorable theatricality,” unsuitable orchestration, and quickly dubbed by some as a “holy text in dubious musical costume” that signaled a strident departure from ecclesiastical, Germanized tradition, and as the “decay of Italian church music” by others, Verdi’s ‘Requiem’ challenged the very construct of religious worship and what it looked like to musically supplicate God. More importantly, it showed that a composer was not beholden to proverbial semantics and axiomatic formulae simply because it was the temporally and ideologically correct aesthetic. Not to mention his ‘sinful’ usage of female voices, which brought another level to the already allegorically engorged funeral Mass. It infused volatile mankind, represented through near-constant juxtapositions of emotion and orchestral insatiability, with a deeply remorseful but still infuriated celestial fire, exemplified through a classic, Italian lyricism with a lacerating sensuality too hot to touch. But just as Verdi, the borderline apostate whose indebted, esoteric reverence for human experientiality, stipulated by some as a type of non-Christian theism –religious in all but labeling–had looked towards the manufactured world’s struggle with anomic dissolution for inspiration, so too did McQueen nearly 130 years later. McQueen, due to his rallying against the ubiquity of high technology processes and its constructional devalorizing of the human hand, was heavily inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement. Both Alexander McQueen and Giuseppe Verdi passionately strove to emphasize the disconcertingly fragile state of mortality to which we are all tethered and not only reify an emancipated alternative but truly create the necessary catalyst for palpable, societal reformation. Therefore, through a surrealist, blanched dress at a fashion show now 23 years past, musically accompanied by Verdi’s unmatched turbulence, the genuine fight for emancipated air stains not only in the dress which is suddenly doused in electric hues of neon green and black paint but in our ears.

As Price’s tortuous immolations to the furious God commence, ensnaring the divine and the damned in a zero-sum-game of mortal petitioning, Harlow emerges from the darkness atop the rotating disk. She is dressed in an exaggerated, strapless dress, writhing in pain between the two cruel mechanized arms. As Harlow spins in confused naivety, unsure of what will or could happen between these robotic appendages, McQueen’s defiance of the attractive auspices of innovation—that is to say, unethical modernism—is seen through this visualization of Man versus Machine. While Verdi rendered music as a violent opponent of societal equilibrium and placative formality, McQueen brutalized naturality. Presenting the damp, spotless model in a state of undressed-yet-dressed and exaggerated rusticity—quintessential visual signatures of Arts and Crafts decorum—flanked by the sentient mechanical adversaries, McQueen highlights the uneasy place between streamlined industrialization and organic imperfection.

In a brutal irony, as Price reaches out for the divine jugular and Harlow tries in vain to shield her body from attacks to come, the audience cheers in unknowing, sacrilegious deviancy, ignorant of their historical proximity to the vulgar Classical debaucheries of ancient gladiatorial tournaments. With every noxious swell and intoxicating guttural invocation spoken by the damned woman, the machines grow more restless, and in return, so does the immolated “vestal virgin.” Just like Stravinsky’s ‘Rite of Spring’ and the ecstatic virgin death which ushers in springtime; the Princess Polyxena’s gruesome death at the hands of Neoptolemus; and the pervasive “death of the virgin” motif throughout Western Christian art representing Mary’s final ascension into heaven, so too here is the pure being butchered by the corrupt—by the robotic arms spraying her white dress in garish paint.

Neither McQueen nor Verdi would have put it so theologically nor apocalyptically. Instead, the “death of the virgin” motif comes in the allegorical suicide of complacency and the modalities of homogeny that saturated life in the 19th-century Fin-de-Siecle period. And it manifests once again, more than a century later, at the Fin-de-Millennium, where sleek and sexy “capitalist modernism” was quickly becoming the dominant sociocultural idee fixe. Comfort had become the prime directive, and nothing was safe, not even the construct of the avant-garde. So the mechanical progeny of 2001: A Space Odyssey’s HAL 9000 have come alive to exact their revenge. At the same time the desperate calls of the non-ascended, the post-Rapture rejects, scream at their fantastic plight.

Verdi wrote his ‘Requiem’ in genuine reverence for his friend Manzoni’s passing. His intimate friend and librettist Arrigo Boito noted his preciseness in the physical funerary preparations; ‘one priest, one candle, one cross‘ (Walker, 1962/2012). Similarly, Spring/Summer 1999 was the only fashion show which brought McQueen to tears, the visceral reaction to the catwalk perhaps due to the designer’s adamant views on female subjugation. He brazenly wrote, “I know what misogyny is. I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.” Within No.13, every garment and their individual aural volume, symbolically but also through Verdi’s demonstrative invocations, radiates McQueen’s mission to exterminate external superficiality and the pleasure induced from skin-deep opinions. As he stated, the goal of the fashion show was ‘to show that beauty comes from within through defeminizing the female form through ersatz virilization or masculinization.

There is a debate to be had about translatable intentionality, not only with music but all creative mediums and their innate ability to be linked together to form polychromatic membranes. In Verdi’s case, this translatable quality comes in the purpose of his formidable Requiem: to rage against the bleakness of mortal conclusion and honor his fallen companion. A more appropriate call-to-action is pointed out by Walker: Verdi was intrepidly opposed and actively rebuking Italy’s embrace of Austro-German compositional and its zealous taste for anatomical perfection on one end and thaumaturgical contrivances on the other. This preferred form of music was most apparent in the ecclesiastical stylings of Bach and Beethoven, and operatic designs of Wagner and Mahler. Known as the Cecilian Movement—a push towards church music reformation as a reaction to the progress made by the Enlightenment—Verdi’s “Requiem” adds a nationalistic hue to its already saturated symbolic frame. But it would achieve another ray, as Verdi was also combatting and operating within a destabilized and agitated Italian society. Having just won the third battle for independence in 1866, after two previous wars in 1848 and 1859, only to be consumed by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, it becomes clear why Verdi’s Italianization of the conventionally Germanic compositional form was more than religious antagonism. He was waging his campaign against the onslaught of foreign influence. This ideological and aesthetic refutation of the watering down of the Italian ethos was a strong motivator for many Italian creatives during the second half of the 19th century.

During the period of Italian Irredentism, fine-artists returned to neoclassicism and Greco-Roman symbology, while writers and composers rallied around patriotic tropes and nationalistic themes with moral/ethical overtones. A prime example is “Nabbucco’s” Hebrew Slave Chorus, “Va, Pensiero,” whose mighty recalcitrance and thunderous sound quickly became the vehicle of Italian patriotism. While scholars debate the actual political themes of Verdi’s operas, it is hard to imagine that such themes were not at least subconsciously imbued in his Requiem, as its premiere in 1874 was only four years after the official conclusion of Italy’s fight for unification; a moment that would only incite further chaos ranging from radical political projects, ill-formed internationalism, colonialism, to eventual fascism. To say that Verdi was a full-blooded Italian loyalist when he, through his librettist for “Attila,” said, “Avrai tu l’universo, resti l’Italia a me” (“You may have the universe, if I may have Italy”) would be a phenomenal understatement. But how does McQueen fit into this all?

He could be considered just as political as Verdi, though through exhibitionist, textile protestations rather than musical declamations. He was intrinsically connected to his Scottish heritage and well-aware of the pillaging of his homeland’s resources and humanity by England in the 18th-century during the failed Jacobite Rebellion. A secondary influence was the irrevocable 19th-century ‘Highland clearances,’ a forced serfdom-qua-eviction of the Highlands and Islands of Scottish residents. Together, with the colonial entrapment and forced emigration, this led to the infamous 1846 Highland potato famine, a part of the broader European potato failure, lasting a decade and causing the sorrowful emigration of nearly 75 percent of the Highland’s population. Both of these incidents were traumatic historical events in the chronology of Scotland and impacted McQueen’s view of the world; so much so that he dedicated an entire show to these events. This was the seminal Autumn/Winter 1995/96 Show called “Highland Rape.” McQueen showed his national solidarity through his usage of tartan kilts and military belting, outlawed under the Duke of Cumberland’s 1746 Dress Act, which had been a vile attempt to kill remaining patriotism through banning all vestiges of Scottish identity. The corollary between Verdi and McQueen is independence and national solidarity. Fully owning and proudly displaying your cultural calling signs with heroism, so much so that an observer is forced to contend with the question of why, in an attempt to decode what they are experiencing and bearing witness to, underwrote all that Verdi and McQueen did.

There is another layer too: the Arts and Crafts through-line. This could be considered the conflict of Machine versus Man, or rather Homogeneity versus Heterodox. Dr. Gordana Vrencoska notes this as the “freedom of cultural expression” (2009). As with McQueen’s iconoclastic extravagances, Verdi’s ‘Requiem’ was unapologetically novel in its seismic extirpations of the day’s compositional formalities and generic traditionalism. His usage of Italianate fluidity, manifested through luxuriant sentimentality and meditative orchestration, paired with the decisive punctuality of the Germanic idiom, read as a war of aesthetic authenticity, one that weighed very much in Italy’s favor.

A pressing question that comes to mind is; can the carnality of the suicide by fire and the furious repudiations against the construct of the doomed man actually do the very opposite to what it had intended? Instead of invoking the sacred spark within the listener and the observer, can these creators’ usage of violence and sacrifice actually distract from the intended goal in mind? I am hesitant to state any definite notion of transcendental blasphemy. Still, the truth does remain that by distancing themselves from their respective norms, they were opening themselves up to forces beyond their control. In Verdi’s case, his aesthetic departure from the Germanic streams of choral solemnity and entrance into an ideological conflagration akin to the very real battlefields that bordered and engulfed his country did much to showcase Italy’s “cuore di leone” (“Lion’s Heart”) despite the internal and external onslaught.

In McQueen’s case, however, by subjecting the female form to public displays of violence at the hands of disinterested assailants, in effect raping her of her virginal femininity—borrowing a trope of Gothic fiction and implying virginity by the blanched purity of her garment—he was professing his scorn at the construction of the womanly ideal and normative conventions of beauty. In my efforts to explore this question of fidelity to the theological or textile, it’s helpful to reference an article called ‘‘Music and Fashion,’ written by Aram Sinnreich and Marissa Gluck in 2014. In a comparative back-and-forth, they investigate the confluence of these art forms from societal, communal, industrial, legal, economic-organizational, and digital perspectives. Each dialectic indicates relevant points which I would like to briefly summarize, as they help illustrate why asking this question of autonomy from unstable source-material is necessary to fully understand why my article is even required. For the sake of this article’s premise, we will take a look at perspectives 1, 2, and 3.

The societal, or as Hannah Arendt calls it “the sticky conundrum between vita activa [active life] and vita contemplativa [contemplative life] and its indefinite building blocks of labor, work, [and] action” (1958). Music is the very fabric of life in this plane if you consider that music is organized sonic noise, and noise is the unfiltered sounds of life in contorted resonances. Sinnreich and Gluck note that music while being this invisible reflector of consciousness in the art of sound, holds life-changing power that forces the listener to contend with it via our sight-dominated culture. Alongside this, fashion has social power, as each seemingly insignificant detail or overlooked pattern conveys a different emotion, one that may not reflect the wearer’s true identity. In an ominous tone, fashion is said to be the “symbolic coding of social power through apparently innocuous means such as shape, texture or color.” Just like Fin-de-Siecle/Belle Epoque in the 1890s can be considered both a Neo-Renaissance of Parisian culture and a cynical martyrdom of the majestic, agrarian past, the rise of 1990s fashion, along with music, lost its way and became caught up in the great machine. Fashion and music changed from ‘class identification to lifestyle articulation.’ No longer could one guess one’s social station based on what they wore or listened to. Was this a good thing? It depends, but according to Arts and Crafts ideology, a balance of artificial and authentic is always looming over the scene.

The communal is the collective experientiality of the musical realm and the unifier of societal strata. Music and fashion bring the many together again. Here, music is stripped to its vital organs, having its skin and extraneous bile removed. So what is music’s intrinsic purpose, and why was it invented for the human race to utilize? The answer is simple: to communicate with each other our feelings and woes, tribulations, and successes. As Sinnreich and Gluck state, music is the “fundamentally communicative, and therefore social, act,” and where meaning is derived from the “differences between sounds, not in the sounds themselves.” Discussions of this notion alone could fill pages, but what is important here is that Verdi and his ‘Requiem,’ reminding humanity of its fickle nature, was a message that spoke to not only Italian crowds but German ones as well, and its message has only become more international. In November 2020 it was played to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Nuremberg Trials. As one can see, when great music is composed it transcends time and geography, defying the laws of science in its inescapable control of the human psyche.

Finally, industrial, where music broke away from the chains of the concert hall, salon or private hall, and became ‘massified,’ socioculturally homogenized, packaged, and sold for instant satisfaction. Fashion became itemized, no longer a tool to find the “I.” McQueen’s fascination with the Arts and Crafts movement found its home in this construct. The movement was a refutation of the industrial takeover of British culture in the mid-19th-century. There was a resultant cultural backlash, a push towards the handmade, the unrefined, the folk, the amateur, led ultimately by humanity’s wish to reclaim agency over their machine-driven existence. Art Nouveau, a style that incorporated the organic spontaneity of curvilinearity, is a prime example of this. McQueen’s usage of the deconstructed, nearly Bauhaus-Esque aesthetic, however, was a commentary on beauty’s superficiality and his attempt to get at what lies beneath the golden facade. In McQueen’s own words, he showcased the “hard edge of the technology of textiles” through his purposefully jagged and functionally unusable garments. What is used when it is nothing but a layering upon which your entire personhood is based? Beauty, in this sense, loses its meaning, becoming nothing but an external mirage for the peanut gallery to feast on. For Verdi, the heavy doses of his sonic eurythmics, which, caused even the most upstanding Christians to check their morals for signs of fault, invoked a similar sentiment. The Mass, in its traditional, Germanic superficiality, exemplified by superb yet hyper-methodical construction, was not representative of the ostentatious Italian spirit and loyalist affinity for passion. Verdi unapologetically reshaped it to fit Italia.

As was aforementioned, the background music McQueen technically used was not Verdi’s ‘Requiem,’ but Mozart’s ‘Piano Concerto in A major, K. 488’, known as ‘No.23′ and ‘19′ by others. This is an energetic piece, dulcetly content at times yet lyrically intrepid at others, which lies squarely within the majestic confluence of Germanic refinement and Italianate rapture. It seems it was Mozart’s personal favorite as well as McQueen’s, considering that this concerto was used among several others to help him win his commission bid. The piece was written chiefly to showcase his technical proficiencies and musicality. This fact makes me wonder whether the music for the widely distributed video matters or not. The concerto’s proclivity towards a voluntary surrender to the natural world, marked by the work’s expert mixture of soloist bravura and orchestral integrity, fits right at home with the Veridian dialectic of Germanic and Italian influences.

Funnily enough, this has been noted before, by Girdlestone (2012): “It is a commonplace to say that Mozart unites features of German and Italian music, and we may recognize here a Mediterranean brightness tempered and moistened by Northern sensibility.” However, while no one can be sure why this particular concerto was chosen, more insights are gleaned from Girdlestone, notably that within the sonorous facade is a deep longing and perpetual sadness that was never entirely satiated. The German musicologist enchanted with a Grecian understanding of music, Hermann Abert, remarked that Mozart held a desire to fully experience life by giving an organized voice form to “this raw material of the spirit.” A striking mixture of juvenile angst yet unresolvable discontentment, Mozart’s immortal adolescence sought more than simple revelries or vivacity. “His interest was not in Nature, but in Culture,” meaning the product of man’s affections, not the affections themselves. Further, even the key signature used holds symbolic merit. A major traditionally is the key of new love and the voice of unblemished trust, both in kinship and God. For Mozart, as he grew, he left A Major behind for more intelligent choices. Still, the potent mixture of joy and tears rings as a catch-all for not only this sonata but for Verdi’s ‘Requiem’ and, most certainly, McQueen’s textile declaration.

All three of these creators, conduits of the variegated pathways of human interactionism, present being mortally aware as neither a consortium of definable elements nor a motley, congealed mass of displaced monikers and place-cards. For McQueen, a textile rebellion was his nonpareil against the post-industrial estrangement of the modern world which had become inebriated on “beautiful” excess and instant gratification. For Verdi, mortal protestation came in a more violent form, choosing momentous bouts of orchestral and choral infernos, offset somewhat by glimmers of angelic absolution just on the horizon of consciousness, to rouse the crestfallen spirit to God’s sonorous abode. As Rousseau wrote in 1762, “I believe…that the world is governed by a wise and powerful Will; I see it or rather I feel it, and it is a great thing to know this.” Indeed, what unifies Verdi with McQueen and Mozart is the need to rationalize and externalize somatic experiences of an uncovered reality so others may revel in its magnitude and indefinite texture. As Shalom Harlow, a stand-in for man’s ego watches as she is set ablaze by silent machines, she finds herself also strangely cleansed by the holy fire.

Categories

Special Features