HamburgMusik 2025 Review: Pastorale

Living Nativity Concert Features Ensemble 1700, Dorothee Mields, Matthias Brandt & Dorothee Oberlinger

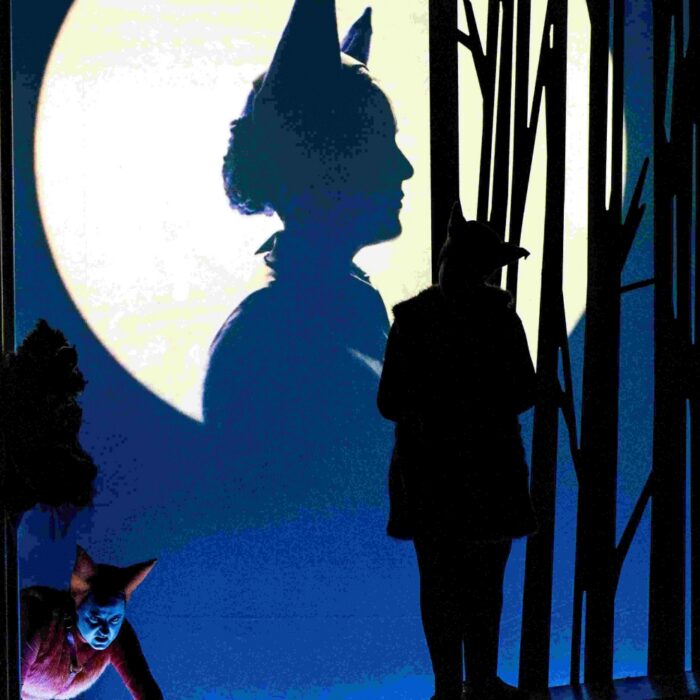

By Mengguang Huang(Photo: Daniel Dittus)

What new ideas can a Christmas concert possibly still have up its sleeve? “Pastorale,” conceived and led by Dorothee Oberlinger with Ensemble 1700, offered a compelling answer by returning Christmas music to its human roots. Rather than polishing familiar repertory into decorative ritual, the concert reframed it—through sound, story, and historical memory—into a richly textured, deeply humane soundscape, where shepherds, pilgrims, composers, and listeners meet across social boundaries.

The conceptual backbone of the evening lay in the ancient Italian tradition of the Pifferari: shepherd-musicians who descended from the mountains during Advent to play before roadside Madonnas and household crèches in Rome, Naples, and beyond. Represented by the ensemble Li Piffari e le Muse, their half-sacred, half-profane music—performed on high-pitched bagpipes, hurdy-gurdy drones, and fiddles—was devotional, practical, and unpretentiously loud.

At the heart of this experience lies the human voice. Dorothee Mields’ crystalline soprano provided the concert’s spiritual axis, combining purity of tone with unaffected warmth. In Alessandro Scarlatti’s pastoral Christmas cantata “Oh di Betlemme altera povertà,” she shaped long melodic lines with natural communicative ease, allowing the music’s gentle wonder to unfold with storytelling sincerity. On stage, Mields’ subtle body sway and expressive gestures mirrored the music’s ebb and flow, while her phrasing remained in constant dialogue with Oberlinger and the ensemble. Here, Scarlatti reveals himself as a master of “high-cultural” transformation: familiar shepherd music absorbed into poised Roman cantata writing. Mields inhabited this space perfectly, her voice hovering between heaven and earth, embodying the cantata’s central paradox—divine birth revealed through humble means.

(Photo: Daniel Dittus)

This sense of elevation made the subsequent descent all the more affecting. After Scarlatti’s cultivated pastoral, the second half of the program turned toward simpler, more grounded expressions of devotion. Francisco Soto de Langa’s “L’unico figlio” and Alfonso Maria de Liguori’s beloved “Tu scendi dalle stelle” stripped away intellectual refinement in favor of direct, heartfelt utterance. Accompanied by “Li Piffari e le Muse” and Oberlinger’s recorder, Mields’ singing became more chant-like, as if leading a communal procession. One could imagine candlelit streets, improvised nativity shrines, and the slow movement of a festive parade, reminding listeners that Christmas music once circulated hand to hand and voice to voice, long before it became a curated seasonal canon.

Arcangelo Corelli’s Concerto grosso in G minor, Op. 6 No. 8 (“Fatto per la Notte di Natale”) emerged as the concert’s emotional keystone. In its dual-recorder arrangement inspired by John Walsh’s London publications, the famous concluding Pastorale gained renewed freshness. Gentle rhythms and sustained bass lines clearly evoked shepherd pipes and drones, connecting the cultivated ensemble writing to the rustic roots of the music. The following Alessandro Marcello’s Concerto in D minor became a personal showcase for Oberlinger’s artistry. From the articulated “Andante e spiccato,” through the ethereal, ornamented “Adagio,” to the dazzling “Presto” finale, she demonstrated technical mastery and charismatic immediacy, transforming virtuosic Baroque writing into a vivid festive image.

Giovanni Antonio Guido’s “L’Hyver” served as a prelude to Vivaldi’s energetic sound world, blending drama with playful unpredictability. Icy string figures and biting rhythms, punctuated by occasional twinkling “little star” motifs, swung between humour and mild disorientation. This tension flowed seamlessly into Vivaldi’s Concerto in C major, RV 443. Oberlinger’s articulation again highlighted the underlying energy, while the central “Largo,” with its gently dissonant strings, offered a suspended, introspective moment—an inward reflective pause amid dazzling technical display.

Interwoven with these vocal and instrumental presences was again the human voice. Matthias Brandt’s narration—drawn from Italian Christmas texts and 19th-century travel writing—animated a collective memory, evoking candlelit streets, roadside shrines, and itinerant musicians arriving from the mountains. With a seasoned actor’s restraint, Brandt responded naturally to the fragmentary bagpipe interludes, connecting devotional reflection, poetic nostalgia, and historical realism, giving voice to those who traditionally stood outside the canon: shepherds, the poor, and the displaced.

The evening’s final arc—culminating in Johann Christoph Pez’s French-inflected “Passacaglia”—offered a resolution both gentle and profound. The “Passacaglia’s” repeating bass patterns and evolving variations created a mesmerizing circularity, each iteration building subtly yet inexorably toward closure. Combined with the warmth of Oberlinger and Li Piffari e le Muse’s pastoral colors, the piece conveyed a satisfying sense of completeness—an audible affirmation of the journey from intimate shepherd-song to virtuosic Baroque splendor, leaving the audience with the lingering echo of instruments glow.

Incorporating cultivated Roman cantata, rustic shepherd chant and virtuosic display, “Pastorale’s” impressive program design offered a living nativity in sound. It balanced dazzling soloist moments, luminous vocal highlights, the fresh and even anthropological presence of Italian Pifferari, and evocative storytelling. This thoughtful interplay created a richly layered, immersive experience—historically grounded yet vividly immediate—reminding listeners why Christmas music, at its best, continues to resonate as a profoundly human celebration.