Gran Teatre del Liceu 2025-26 Review: Tristan und Isolde

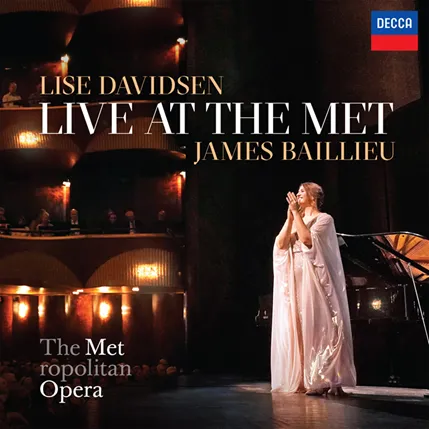

By Ossama el NaggarBarcelona’s venerable Teatro Liceu hasn’t experienced this level of anticipation in a decade. It may be surprising that Wagner would stimulate such activity in a Mediterranean city, but the city of Gaudí is the most Wagnerian of Spanish locales and it’s long had a connection to the composer’s works. But that aside, the likely reason for the excessive buzz was thanks to Norwegian soprano Lise Davidsen, who burst onto the scene with great promise several years ago.

Fond memories remain of being mesmerized by Davidsen in the 2019 production of “Fidelio” in Montréal. She’s a young singer with a powerful, beautiful voice, devoid of affectation or mannerism. In 2022, her performance as Giorgetta in Puccini’s “Il Tabarro” at Teatro Liceu confirmed her immense talent, even in repertoire not associated with her. However, her Leonora in the Met’s “La forza del destino” was disappointing, hinting at the talented Norwegian being led astray into unchartered territory with insufficient conviction and preparation. Fortunately, this opening night of “Tristan und Isolde” on January 12 restored hope that Davidsen may soon be the absolute queen of Wagnerian performance.

The rest of the cast was equally impressive, especially Tristan, the American dramatic tenor Clay Hilley, who impressed with his bright voice and formidable endurance. Rarely have I heard a tenor conquer the third act with as much stamina, while also capturing the dying hero’s frailty. Thanks to this mix of infirmity and vocal stamina, his long scenes with his faithful servant (Polish baritone Tomasz Konieczny) were riveting. The latter, one of today’s leading Wotans who’s mastered the Wagnerian repertoire, is also gifted with impressive diction. His despair at his master’s physical condition and mental delusion was truly affecting, eliciting more tears than any other scene.

Russian mezzo Ekaterina Gubanova, who sang Brangäne at the last Bayreuth Festival, repeated her touching portrayal. Unlike Gubanova’s other performances of the role, her Brangäne in Barcelona was distinctly that of a devoted servant, neither maternal, as is often the case, nor a responsible older sister. Despite a slight vibrato that some might find bothersome, her creamy mezzo contrasted well with Davidsen’s soprano.

British bass Brindley Sherratt was a competent King Marke, more avuncular than regal. Only the most charismatic of singers can render King Marke’s Act two lament riveting, the one in which he surprises his adulteress wife and disloyal nephew. Thanks to the impeccable conducting of Finland’s Susanna Mälkki, his lament was not soporific, but still, it was the least exciting part of the performance. Indeed, much of the success of the evening is owed to Mälkki, who masterfully directed the Orquestra Simfònica del Gran Teatre del Liceu.

The score of “Tristan und Isolde” is unique in the Wagner canon; the voices dominate and the orchestra accompanies en veilleuse (on the back burner). Mälkki’s reading was one of the most thrilling I’ve ever heard in live performance. This was a relief, as her recent performance of “Le nozze di Figaro” in Munich was an utter bore. Considered one of today’s leading conductors, Mälkki is (unsurprisingly) strong when directing works she finds thrilling, such as the present opera. The minor roles were competently portrayed by local singers who managed to have decent diction.

With Mälkki’s conducting and a superlative cast, this could have been a historic event. Alas, Barbara Lluch’s staging was the weakest of any production of “Tristan und Isolde” I’ve ever seen (and I’ve seen many). Wagner’s monumental opera is no trivial work, and for a competent director, it’s a treasure trove of potential ideas. In all likelihood, Lluch did not spend much time in conceiving her staging. Many were surprised this director was assigned to this work, for she rarely impresses. Her sole claim to fame is that her grandmother was noted director Núria Espert. A 2017 production of “Tristan und Isolde” at the Liceu by Àlex Ollé, one of the six artistic directors of La Fura dels Baus, highly praised at the time, ought to have been revived.

Two aspects characterize Lluch’s staging: a dearth of ideas, of innovation, and the stagnant development of characters, save for Isolde. To stress Isolde’s wrath against Tristan for having killed her betrothed and feigned being Tantris while she nursed him back to health, we have an enactment of a conseil de famille of Ireland’s royal household midway through Act one’s first prelude. The very notion of disturbing the public’s appreciation of the sublime music, especially with such a brilliant conductor as Mälkki is outrageous in itself. An older version of Mélisande, the other Celtic feminine prototype, with the usual long but gray hair is obviously Isolde’s mother, the Queen. There is also a young man, likely her brother, and an old man, her father, the King, They assemble around a table on which there’s a severed head, a clin d’oeil to John the Baptist’s, in Strauss’s “Salomé.” The only effect this grotesque scene had was shock value.

In Act one, Brangäne is aggressively manhandled by the crew of Tristan’s ship. The purpose of this scene is not clear. Perhaps it was a diatribe against the brutality of the male sex. If so, Lluch is in the wrong opera, for this topic, as significant as it is, isn’t warranted here.

In Act two, Isolde, in a red dress worthy of Violetta in Act one of “La traviata,” is clearly under the spell of the love potion, and acts like a silly child. The grimaces and mannerisms are excessive, not at all in keeping with the solemnity of Act two’s love scene. If this is what love looks like, then it’s to be avoided at all costs.

In Act three, Isolde arrived in a ridiculous white wedding gown; a simple white dress would have sufficed. In the same act, Tristan is dressed in unflattering garb and seated in a stylized setting resembling Ariadne’s rock in Strauss’s “Ariadne auf Naxos.” On top, there is a mirror reflecting the scene. It’s unclear why Tristan comes here, or why a mirror is required. These are likely mere whims concocted by Lluch for reasons unknown to anybody.

In my extensive history chronicling opera, rarely have I experienced such stark contrast, between superlative musicality on the one hand and fatuous staging on the other. It’s unfortunate, but I fear I’ll forever associate Davidsen’s historic debut as Isolde with Lluch’s frustratingly inane staging. It did not have to be this way.