English National Opera 2025-26 Review: Partenope

Man Ray’s Salon: Where Baroque Meets the Jazz Age

By Mengguang Huang(Photo: Lloyd Winters)

Händel’s “Partenope” has always occupied an unusual place in his output: admired by connoisseurs, overshadowed by his more solemn opera seria, and still rarely staged today. Yet this revived 2025 London Coliseum production—delivered with defiant vitality amidst the ENO’s institutional turbulence—makes a persuasive case for the opera’s brilliance. Led by a compelling young cast including Nardus Williams, Hugh Cutting, and Katie Bray, the evening reminds us that Handel’s voyage into comic opera is indeed an inventive, psychologically vibrant work that thrives on performers who can balance vocal virtuosity with quicksilver theatrical wit.

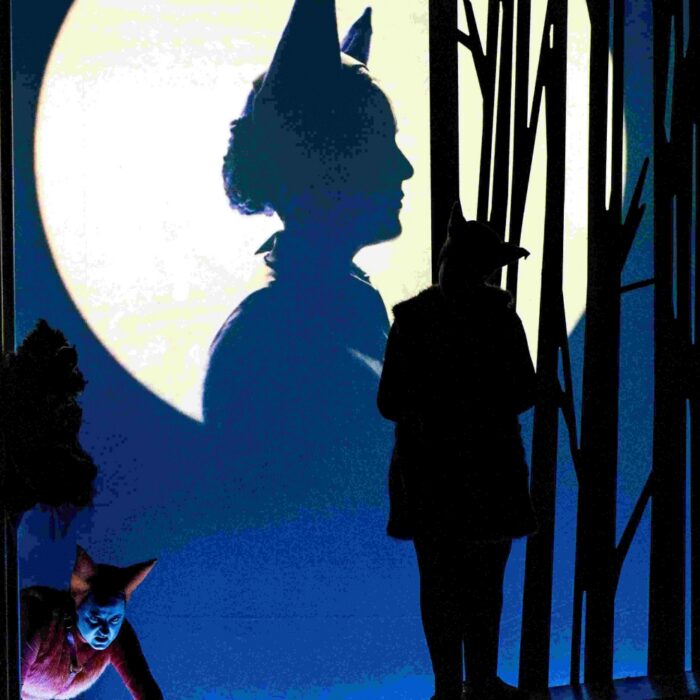

The staging, heavily influenced by the surrealist photography of Man Ray and the chic aesthetics of 1920s Paris, transports the mythical Naples to an inter-war salon. The set design is dominated in the first half by a sweeping, sculptural white spiral staircase that curves elegantly from the flies to the stage floor. Against stark white walls, the stage became a canvas where individual characters, clad in highly saturated, distinctively colored suits and gowns, popped with vibrant theatricality. Their dramatic forms, often posed in sculptural tableaus across the staircase’s tiers, cast looming, distorted silhouettes on the walls—cleverly externalizing the subtext of hidden desires and power dynamics. This minimalist, high-contrast aesthetic allowed the complex geometry of the lovers’ entanglements to take center stage, unburdened by heavy baroque scenery.

The production’s visual dramaturgy shifted effectively in later Acts, moving from the cool, clinical whites of the opening to a claustrophobic, amber-hued room that suggested a late-night speakeasy. Here, beneath a dangerously low-hanging white chandelier and amidst walls plastered with collage-like paper, the opera’s central metaphor—love as a gamble—was literalized around a card table.

Illuminating Cast

At the apex of this stylish world stood Nardus Williams as Partenope. The role was originally sculpted for Anna Strada, and Williams made clear why Handel designed a score with only one truly high voice at its center. Admittedly, her vocal production might occasionally trade Baroque clarity for a more modern, full-blooded resonance, yet in a staging this bold, such stylistic quibbles felt entirely beside the point. Dressed in dazzling silver flapper attire, she commanded the stage with a mixture of regal authority and jazz-age nonchalance. Whether descending the spiral staircase with a martini in hand or dominating a chaotic scene atop a table, her physical ease matched her vocal prowess. Williams shaped her arias with brilliance—luminous legato and gleaming high notes—perfectly capturing the whimsical, seductive character that Stampiglia’s libretto demands.

Within this setting, the supporting cast thrived. Hugh Cutting’s Arsace was a revelation. With a countertenor voice of expressive depth and elasticity, Cutting navigated the role’s virtuosic demands while portraying a man torn between remorse and vanity. His Act two scena was a highlight; amidst the visual noise of the “party,” he managed to draw out a tender pathos, creating a moment of profound stillness. Opposite him, Katie Bray delivered a superb Rosmira—disguised as the male warrior Eurimene. The 1920s setting allowed for a seamless gender-bending aesthetic, with Bray donning a sharp suit that complemented her incisive vocal agility. The tension between her and Cutting at the card table possessed both theatrical snap and genuine emotional stakes.

Jake Ingbar, as the ardent Armindo, brought a welcome clarity with his elegant lyric countertenor, capturing the character’s earnest vulnerability. Ru Charlesworth’s Emilio was delivered with unrelenting energy, his bright tenor cutting through the texture. Sporting a disheveled shock of red hair, spectacles, and a tweed jacket over a pleated kilt, Charlesworth cut a figure both absurd and menacing. He was a masterclass in aggressive entitlement, commanding the stage with a rigid, almost manic intensity that perfectly suited a suitor who treats courtship less like romance and more like a military campaign – a bizarre, often hilarious blend of academic eccentricity and implacable aggression. Rounding out the cast, William Thomas offered a resonant, commanding Ormonte, bringing architectural solidity to the ensembles.

The evening had its own offstage drama when conductor Christian Curnyn fell ill after Act one. Assistant Conductor William Cole stepped in with remarkable composure. Though performing on modern instruments, the ENO Orchestra navigated the shift with impressive assurance. While the basso continuo textures occasionally felt perfunctory and monochromatic—lacking the rhetorical imagination of period ensembles—overall energy never flagged under Cole. The playing retained articulate buoyancy, ensuring arias breathed organically despite the disruption.

Ultimately, this “Partenope” reveals why the work is so beloved by those who know it. It offers a convincing range of human emotions, dazzling vocal writing, and orchestral beauty. What was once dismissed as too frivolous emerges at the Coliseum as a refined, witty, and visually sumptuous opera. With Christopher Alden’s production acting as the anchor, and a musical team that proved its mettle under pressure, “Partenope” is not merely a rarity revived but a persuasive argument for the opera’s rightful place among Handel’s most inventive stage works.