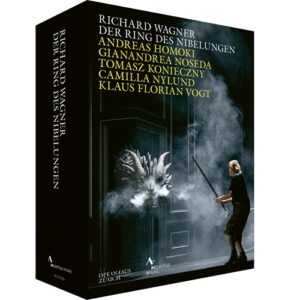

DVD Review: Zurich Opera’s ‘Ring Cycle’

By Bob DieschburgHistorically, Wagner stagings have stirred up controversy. They are–to put it bluntly–like a fashion show: seasonally recurrent, fanciful (for better or for worse), and tailored, if you will, to fit just about anything, the blatant as much as the abstruse.

New productions, then, warrant a healthy degree of skepticism–especially when, as so often happens, the integrity of the work is at stake. The Ring Cycle, for instance, has long been a playground, on which visionaries of varying caliber have exercised their imagination.

Zurich opera’s version of the tetralogy–devised by Andreas Homoki and published, on DVD, by Accentus Music–does not exactly fall into that category. Though iconoclastic in some respects, the staging remains oddly conservative in others; but most importantly, does it spin a coherent narrative across 15 hours and some 20-odd minutes of music? There are legitimate doubts.

For practical reasons, this review will discuss the cycle’s operas one by one.

Das Rheingold

The introductory “Das Rheingold,” unsurprisingly, sets the tone and, in terms of Homoki’s concept, works best. The Hungarian director opts for a pseudo-contemporary set design, which–complete with a rotating stage–evokes 19th or early 20th century bourgeois interiors.

As such, the floor-to-ceiling walls, with white panelling, recur throughout the tetralogy, irrespective of the scenery intended by Wagner. The myth’s elemental diversity–the contrast between the aquatic (think of the Rhinemaidens) and Alberich’s fiery Nibelheim–is irrevocably lost in translation.

The water-nymphs, for instance, appear dressed in nightgowns, jumping on beds and chasing each other around. And looking ahead–to the first act of “Götterdämmerung”–where is the red shine of Brünnhilde’s so aptly described “feurige(r) Schwall?”

The staging falls short of Homoki’s declared intention not to “serve the audience a ready-made interpretation” (as per the booklet) in another, perhaps unintended, way. By shifting the stage action indoors, Homoki forfeits the time dimension of Wagner’s storytelling, which–traditionally–has the action of “Das Rheingold” span an entire day: from Wotan’s awakening in the morning to sunset, when the gods cross the rainbow bridge to enter Valhalla.

Gripes aside, there is a good deal of succinct cleverness in Homoki’s production. Valhalla, for example, is depicted as a painting. When the giants Fasolt and Fafner first appear, they sit atop its oversized frame–as if to illustrate the dynamics of power.

Similarly, Wotan’s self-deception becomes painfully clear when he demonstratively shuts the door as Alberich curses the ring: “Meinem Fluch fliehst du nicht!” Equally perceptive is Loge’s leap back into Nibelheim; it makes the very end of “Das Rheingold” prefigure, so to speak, Valhalla’s eventual destruction by fire.

The cast is kept in constant motion—if not frenzy. This is especially true in the second scene, when the giants arrive and general commotion ensues, reminiscent of Barrie Kosky’s “Meistersinger” from Bayreuth.

Here, the stage direction aligns well with the inherent comedy—the witty, even silly retorts, particularly from Matthias Klink’s Loge (whose resemblance to Disney’s famous pirate captain may feel a tad overstated).

The family politics, much like in a Kammerspiel, are all fleshed out. Tomasz Konieczny—as Wotan, notably without an eyepatch—sits at the very heart of this tragicomedy, stripped of his godly aura; he is at the mercy of his wife and strives to restore domestic peace.

Gestures and facial expressions are consistently over-the-top, and the use of stage props can, at times, seem overly deictic. Nevertheless, Homoki finds a throughline to which he remains faithful–even if, for variety’s sake, the scenery of Nibelheim could have stood out more.

Musically, Gianandrea Noseda–who is Zurich’s Generalmusikdirektor–offers swift tempi and a pronouncedly theatrical, if unsymphonic interpretation of the score. While the Philharmonia Zurich pays close attention to detail, it does not indulge the sonic spectacle of, for instance, Wotan’s “Abendlich strahlt der Sonne Auge.”

Everything feels contained–in a good way, but one should not expect Karajan or even Solti when buying into Noseda’s vision. For “Das Rheingold,” however, it holds considerable validity.

Christopher Purves replicates this kind of stringency admirably. Conversational in tone, his Alberich is endlessly varied; one appreciates, for instance, his snarly mezza voce—almost like a whisper—and intrinsic maliciousness.

Klink, by contrast, is but an imperfect match for this sort of genius ruffian. As Loge, he conveys the trickster’s subtlety, though—as a matter of personal taste—I find his style a little too declamatory, as the example of Peter Schreier looms behind many a note.

Dominant as Fricka, the German Claudia Mahnke is in extraordinarily fine form—but what about Wotan?

Konieczny’s portrayal hovers between his undeniable strengths–chiefly as an actor–and some stubborn idiosyncrasies, if not weaknesses. While not exactly pleasant, the sharp edge of his tone commands attention–particularly when paired with his forceful stage presence.

But over time, the persistent distortion of vowels combined with syncopated lines tends to sour on the ear. Moments that call for lyrical breadth like “Vollendet das ewige Werk,” for instance, may feel uncomfortably… well, unlyrical, whereas the speech-inflected back-and-forth of subsequent scenes serves him far better.

Die Walküre

The transition from “Rhinegold” to the tragedy of “Die Walküre” is rather unspectacular. The décor remains unchanged; if anything, it appears sparser and more subdued. The walls are lit in off-white, and the ash tree looms darkly over the few remaining props.

This monochromaticism quickly becomes tiresome, as even stage effects–such as lightning bolts–fail to distract from the scenic vacuum that Homoki seems, despite himself, slightly at odds with. This might explain his decision to have Wotan roam the stage well before his prescribed entrance at the start of Act two.

Consistent with Homoki’s portrayal of Wotan in “Das Rheingold,” he remains a schemer, reduced to a prosaic, or even human, scale. He is a tragic figure, driven by the compulsions known to the initiated (in 20th century musicology) as Wotanszwang. Yet the implied grandeur—in my experience—did not perspire neither in the narration nor the farewell.

It didn’t help that I secretly wished the orchestra had put more weight behind the brass—in a bid, perhaps, to emulate those classic interpretations that have so shaped the sonic identity of the Gesamtkunstwerk.

Noseda—speedy and compact—gives precedence to cohesion rather than pathos; so does Konieczny, whose declamatory, if not colloquial, style eschews vocal magniloquence.

Wotan’s decree, for instance, is not delivered in a single breath; rather, Konieczny breaks up the line—“Wer meines Speeres Spitze fürchtet”—much like one does in everyday speech. This logocentrism sets the Zurich performance apart—and distinguishes it from earlier ones (notably his 2016 run in Vienna).

Enter the Valkyries, emissaries of death… outfitted by Christian Schmidt as Monty Python-esque survivors of an off-brand fashion gala. With their equine headgear, they are certainly whimsical—though why Schmidt, in a metonymic twist, depicts them as horses rather than riders is quite beyond me.

In any case, Camilla Nylund–as Brünnhilde–stands vocally at the intersection of lyricism and dramatic intensity, which renders the stillness of the Valkyrie’s annunciation of death (“Siegmund! Sieh auf mich!”) preternaturally eerie.

It’s a nice touch, particularly in conjunction with Eric Cutler, whose steely and heroic Siegmund is firmly grounded in tradition. Yes, his delivery of “Ein Schwert verhieß mir der Vater” may be accused of fogyism but I have a penchant for this kind of old-fashioned stance on vocal power.

Daniela Köhler falls into the same category: a tad one-dimensional (but then again, who among Wagner’s characters isn’t?), her Sieglinde radiantly conveys the rapture of sisterly love.

Siegfried

With “Siegfried,” the emphasis on color and reduced scale—in short, the score’s fine print—truly comes into its own. After all, it is the tetralogy’s scherzo, so to speak.

The orchestra takes on an almost Italianate stance: from the curvaceous lines of the coloratura-inflected Woodbird to the Verdi-esque passion of Brünnhilde’s Awakening–within reason, that is.

And while bombast was never to be expected, I still found the innate vitality of Noseda’s direction quite subdued. The duet felt as if, after a while, the effusive love–”Leuchtende Liebe, lachender Tod” –actually became rather tepid. Of the entire cycle, this may be where Noseda convinces least… but the video edits are at their very best!

Tieni Burkhalter–in a smart and unintrusive way–opts for a series of close-ups: stretched-out hands and awed faces synecdochically capture the essence of Wagner’s score.

The apparent vision of Andreas Homoki, on the other hand, feels notably agnostic. It centers primarily on a pervasive black-and-white color scheme and an–admittedly realistic–Fafner, whose position echoes the transformation of Alberich in “Das Rheingold.” For the rest, it remains fairly conventional.

Konieczny’s Wanderer, by contrast, is anything but commonplace. From defiance and authority projected in the Riddle scene to the final unraveling of his might—his Wanderer is articulate, eloquent, and incisive. Walter Legge, to draw a comparison, coined the phrase “the acting voice;” it perfectly suits Konieczny’s characterization. As for tonal beauty, however, his vocal production remains unorthodox.

David Leigh is a cavernous Fafner (he also reprises the part of Hagen), while Ablinger-Sperrhacke delivers a manipulative–yet no less pitiable–Mime, free of Semitic or otherwise grotesque caricature.

But as much as they matter, the success of “Siegfried” ultimately hinges on the eponymous hero. Cast against tradition–he is no true Heldentenor–Klaus Florian Vogt is not particularly nuanced on the mico-level; but the silvery purity of his timbre fits the bratty forge-scene youth like a glove.

At times, his lightness may risk to flatten the stakes–like in the confrontation with the Wanderer. Yet with his crystal diction (and wide-eyed facial expressions), he endears himself as a boyish, strangely angelic renegade who has carved out a niche for himself–well outside clichéd territory.

Götterdämmerung

More than previous parts, “Twilight of the Gods” intertwines Wagnerian mythology with real-world politics.

It introduces structural opposites with clear musical equivalents: the Gibichungs, for instance, have a choral scene–unique within the tetralogy–which, as Homoki explains, is associated with the human sphere.

There’s plenty of potential, then, for integration into the scenery. Yet the visuals do not deviate from what we’ve seen before. The action is still framed by panelled walls that offer no means to represent time. Hagen slays Siegfried at dusk, the funerary procession takes place at night–but we wouldn’t know it!

More than ever, Homoki follows Wagner’s directions very selectively. The Immolation scene, in particular, becomes a kind of cinematic playground, for which every stage rotation yields a new tableau.

This undermines the cohesion the director–for better or for worse–had maintained across previous operas. But really his interpretation of the finale makes his concept fall apart: Siegfried, now dead, is revived in a barren (liminary) space–save for an Empire-style bed, on which he rests, and the Valkyries’ horsehead. He is joined by Brünnhilde, as she sings her farewell; he removes the ring, and–oh, sentimentality, on which Wagner would frown!–they share a final kiss goodbye.

Needless to say, to the uninitiated it seems that Homoki, in just a few minutes, undoes some of his best ideas. The only saving grace comes before the curtain call: the reappearance of the Wanderer, seated before the painting of Valhalla engulfed in flames. It offers a moment of iconographic closure that deftly ties up loose ends.

Noseda reprises the level of detail for which he set the bar in “Siegfried.” Evidently, the strings form the backbone of his coloristic palette–poetic in the Dawn motif and the Rhine Journey with its woodwind arabesques.

The natural imagery resonates with Noseda; he finetunes his orchestra and–significantly–avoids the broadband sound by some of his predecessors. As before, his diminished emphasis on scale yields an uncanny liveliness–a dynamic that slower, or perhaps more bombastic, takes would often miss.

For the singers, his restraint is a godsent. It allows them to phrase freely and–like Klink in “Das Rheingold”–to prioritize a logocentric delivery. Granted, Vogt is still very much indebted to his innate lyricism, but Christopher Purves, as Alberich, proves a master of Wagnerian Sprechgesang. In the Night scene of Act one, he proffers an ingenious array of snarls, sottovoces, and declamatory threats. It is as sinuous a characterization as any on record.

I already pointed out the inconsistencies of Homoki’s Immolation scene; yet Camilla Nylund, too, is not without flaw. Trenchant and crystalline, her tone tends to narrow under pressure, and while finely spun, it lacks some evenness.

In short, this is not the catharsis one might have hoped for; the dramaturgy feels more suited to a third-act “Manon Lescaut” than to the solemnity of Brünnhilde’s sacrifice. It’s speculation whether this constant frenzy affected Nylund’s rendition.

In any case, the scene–with both merits and blemishes–metonymically stands for the Zurich “Ring.” In spite of its many serviceable choices, it occupies a liminal space, grounded neither in tradition, nor overt modernity or Regietheater.

This niche could eventually prove advantageous, especially in light of new productions scheduled in Paris, New York (under Yuval Sharon), and Bayreuth. Whether it endures remains to be seen.