Dutch National Opera 2022-23 Review: Rusalka

Johanni van Oostrum Headlines Starry Cast in Strange Production of Fairytale

By João Marcos Copertino(Photo credit: Ⓒ-Clärchen and Matthias Baus)

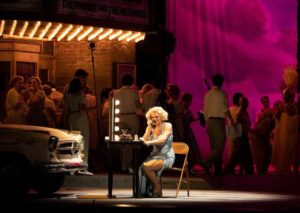

Something in the Zeitgeist tells us that the old saying “Dreaming is free” is no longer true. If the box-office bomb “Babylon” explored how much the Hollywood dream can cost, and it costs a lot, both in the film and in the box-office. Philipp Stölzl and Philipp M. Krenn’s take on Dvorak’s “Rusalka” follows a similar path in displacing “Rusalka” from its mythical nature to a dangerous twentieth-century New York City where prostitutes, not nymphs, seek to be Hollywood stars.

It is an inversion of things, the magic is an insufferable reality, and reality is where the dangerous magic actually takes place. Rusalka is an unbelievably naïve prostitute, and Vodník is her pimp. Her transformation into a human being is made by a Jezibaba, a hairdresser that escaped some Blaxploitation-meets-body-horror movie. The prince is a Gene Kelly wannabe, more narcissistic and less charismatic than in more conventional productions.

The conceptualization is, to say the least, out of the box. But, believe it or not, it does work sometimes. Especially in the first act. The references to “Singing in the Rain” were tender. Rusalka’s song to the moon, while contemplating injecting drugs to herself, brought a sense of vulnerability that was shockingly moving. My main issue, however, is that the realism of the staging conception seemed to forecast a certain form of dramatical urgency that was absent in the second and third acts. Nothing in that to prevent the enjoyment of the average operagoer, but it is hard not to wonder the degree to which the absence of magic also makes the opera less realistic.

The main asset of this “Rusalka” is the strong synchrony of the cast and orchestra. Rather than having stand-out singers, the whole cast had a similar kind of strength and capacity, and this is no small thing.

Stars of the Night

The night’s prima donna, South-African Johanni van Oostrum, was a remarkable Rusalka. In a production that explored the trashiness and struggles of urban life, Oostrum compellingly constructed a character that has both the potential to sublimity and the underlying sense of weariness of a woman who has been through the toughest of lives. A difficult effect, she achieved it with beautiful phrases that often had angular moments to sharply remind us that the beauty sung is an aspiration more than an aesthetic reality. Her voice has a fresh lyrical core in all registers, to which, especially in the second act, she sometimes introduces a harsher note or phrase where the music requires a sense of raw emotion.

Few singers are so well-acquainted with the role of the Prince as Pavel Černoch. The Czech tenor gives to the character solid phrases and a great voice. His high notes are particularly pleasing with a covered sound that reminded me of singers of the vinyl era. In this staging, with the help of the great costumes by Anke Winckler, Černoch made his prince a self-absorbed man. His narcissism seems like a parody of these alienated film starts, but when the cameras are rolling, in this production there are cameras literally rolling, his talent can suspend time. His aria “’Vidino divná přesladká,” sung while shooting a car-race scene, was a showcase of technical precision.

Maybe the most charismatic voice of the night was that of American mezzo-soprano Raehann Bryce-Davis. Her instrument combines very rare characteristics in mezzo-sopranos and contraltos, blending warmth and youthfulness. I totally understand the stage-directors’s decision of making Jezibaba a figure more welcoming than a merciless witch. It would be hard to justify making such a beautiful voice represent pure evil. Nevertheless, Bryce-Davis’s Jezibaba is as dangerous as she can be. A doctor of horrors, she will eat you alive as an amuse-bouche.

Russian Bass Maxim Kuzmin-Karavaev sings Vodník with much tenderness and charm. His voice, extremely clear and fresh, gives to the character a sense of guiding and caring that is unexpected from a pimp, but provides a sense of hope to the production.

The cast is complemented by German soprano Annette Dasch as the villainess Foreign Princess. Clearly enjoying herself on stage, Dasch did not escape any of the stage direction’s vulgarities. Her voice worked perfectly well as a counterpoint to Oostrum’s Rusalka: Dasch has a similar instrument, furthering the sense of a Doppelgänger. But where Oostrum sang with candor, Dasch sang with a piercing sharpness.

Last but not least, what a privilege it was to hear the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra playing an opera. The orchestra, under Joana Mallwitz’s command, showed immense musical intelligence. Everything sounded precise, well-inflected and most importantly, at no moment were the singers covered by the orchestral sound. It is amazing to listen to one of the best orchestras, if not simply the best orchestra, in the world showing a sense of collaboration that has unfortunately become rare nowadays. Mallwitz’s reading was profoundly lyrical, and respectful of both Dvorak’s music and Stöltzl’s staging. Although scenically the night was a bit frustrating, it was an incredible performance from all the musicians.