‘Don Carlo’ Or ‘Don Carlos’ – What is the Best Version of Verdi’s Titanic Masterwork?

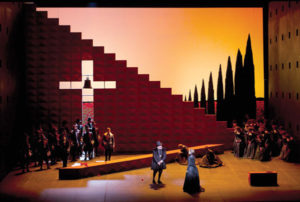

By David SalazarVerdi’s “Don Carlo” makes its return to La Scala for the first time in decades in its five act version.

For many this is the best version of the opera, but the bottom line is that there is no such thing as a real version of the opera with differing versions having different strengths. The work premiered in 1867. Heavy revisions came in 1884 (the so-called “Milan Version”) and then again 1886 (the “Modena Version”). But how many versions of the opera actually exist? And which is best?

The truth is that there is no such thing as the definitive version of “Don Carlo” and different versions feature additions or subtractions regardless of whether they are in four or five acts.

Here is a survey of where to find some of the differing versions of the opera and their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Four Acts

Verdi created a four-act version in Italian in 1884. This version was rather popular through most of the 20th century with many of the world’s greatest interpreters, including its most famous exponent Franco Corelli, preferring the reduced version of the work.

The reason is rather straightforward. The original version of the opera extended to close to five hours (more on this later) and Verdi’s revisions trim away much of the dramatic fat, giving the work his trademark dramatic propulsion. Without the opening act, the tenor has a lot less to sing. This is a fine thing when one considers how challenging the role gets thereafter.

Of course this version has one major drawback, an infamous one at that.

Without the opening act Fontainebleu scene the love between Carlo and Elizabetta is impossible to truly empathize with. We are repeatedly told about how they had hope of being together but without experiencing it first hand through Verdi’s gorgeous music, the audience has no connection to the hero’s plight. There are musical callbacks, but it does little to truly replace 30 minutes worth of romance.

Five Acts in French

Now things get a bit dicey and challenging. Verdi’s original work is in French but when he revised it in 1884 he essentially rewrote entire sections. There are recordings of the work in five acts, such Claudio Abbado’s with Plácido Domingo in the lead role, but the change is only in language as it features the opera with the 1886 musical revisions.

We must look to two other versions in recent times to get a sense of Verdi’s original intention. The most famous one is the Théâtre du Châtelet version from 1997 conducted by Antonio Pappano that stars Roberto Alagna alongside a star cast that includes Karita Mattila, Jose Van Dam, Thomas Hampson and Waltraud Meier. This version restores the original versions of many scenes including the Carlo and Rodrigo duet in Act 2, the original duet between Rodrigo and the King, the original mask scene before the Act 3 trio; the original Act four duet and the final meeting between Carlo and Elizabeta. There is also the addition of the lament of Rodrigo’s death scored with music Verdi eventually used for the Requiem’s Lacrimosa. It is worth noting that the opening of this version does not have a prelude or opening chorus.

While it is undeniably an interesting academic study, there is little doubting that when compared musically with the 1884 revisions, this version is inferior in many ways. Rodrigo and Carlo’s duet has some unique melodic invention but the transitions from one section to another often feature rather bare orchestral accompaniment. The Rodrigo and Filippo duet lacks the dramatic punch of the Italian revision, the duet never truly having a major turning point or building to the climax in which Rodrigo truly challenges the King on his deeds. The addition of the mask scene definitely adds to the drama, adding more depth to Eboli’s dreams of winning over the Prince and thus giving her later anger more potency.

The ending of the opera is the most radically different with Carlo and Elizabeta’s interactions rather limited. Carlo explains his dream over a weighty musical crescendo before the two launch into the second part of the duet and eventually the final confrontation.

This version is far longer than the Italian five act version and yet it is not the most thorough of the releases. That honor belongs to Bertrand de Billy’s version with Ramon Vargas, Iano Tamara, Nadja Michael, Bo Skovhus and Alastair Miles. Clocking in at a whopping 247 minutes (a little over four hours!), it includes all the original music including the prelude, opening chorus, the ballet and judgement scene at the very end of the opera. It is a rather thorough concoction for those that pride themselves in completeness. Again, the music lacks in this version in many instances and the extended finale, while interesting in how it portrays the trial, does not necessarily answer any of the questions the opera’s ambiguous ending leaves behind. Not to mention that it is four hours long.

Five Acts in Italian

With the five act Italian version there are even more variations than one might expect.

The standard five act version from 1886 features the original Fontainebleu scene without the prelude or opening chorus and the four acts from the modified Italian version. With the addition of Don Carlo’s opening aria in Act 1, the edited aria “Io l’ho perduta” is excised.

For many this is the best overall version and arguably the most performed in modern day productions. You can see that in the Royal Opera House’s recent undertaking of the opera with Rolando Villazón in the lead role or recordings by Carlo Maria Giulini and Sir George Solti. This is balanced in many respects, the length is manageable and for the most part it includes the best of Verdi’s music.

But it is not perfect. The lack of the opening chorus and their plight saps Elisabetta’s decision of dramatic prominence. Seeing them plead with her at the start establishes that she not only knows of their pain and suffering but also sees it. When she is asked to decide between her personal needs and those of the people she rules, the audience knows why she makes the decision she must. Without it, it feels forced on the drama rather than truly earned. It can be overlooked for the most part, but it is infinitely better with the addition.

The same goes for the omission of the “Lacrymosa” passage. Without it, Don Carlo and his father go from quickly mourning Rodrigo to the crowd entering the prison. Rodrigo’s death is thus passed over by the two people to whom it matters most.

The third act also suffers a bit dramatically. The prelude that opens the act is gorgeous to be sure, but there is an awkwardness about Don Carlo entering the courtyard expecting to find the Queen only to find the Princess. We never get an understanding of why this happens. It is a problem that plagues the four act version as well.

To solve these issues, some versions have taken to making additions and re-inserting prominent scenes to fill in gaps.

James Levine and Claudio Abbado were major exponents of reinserting the opening chorus and prelude to the dramatic proceedings, setting the stage for the opera and its political and social context in a far deeper way.

Abbado went a bit further however, adding in even more scenes to the opera. He reinserted the mask exchange between Elizabetta and Eboli. He reinserted the mourning of Rodrigo. And for good measure he even included the judgment scene that concludes the opera. This amalgamation is by far the most complete and possibly compelling dramatically and musically, though the ending ultimately comes down to taste. Do you prefer the thunderous musical passage to end the opera or the quite choral hymn?

Some might also have their gripes about the passages that never got proper Italian translations. You can see this in Don Carlo’s statement preceding the ensemble that mourns Rodrigo’s death. The original French fits smoothly both musically and rhythmically while it is quite noticeable how extra syllables in Italian make the line a bit choppier and uneven overall. It is a small matter, but one that arises when seeking out the respective merits of versions.

Antonio Pappano recently tried a similar experiment at Salzburg.

Of course adding all of these scenes brings the opera just under four hours, which remains a point of contention. But regardless, experiencing “Don Carlo” is a massive undertaking in five acts, regardless of the version.

Which is your preferred version of Verdi’s “Don Carlo(s)?”

Want to read other similar essays and analysis on Verdi’s greatest operas?

You can read on the Religious structure in “Otello,” or Verdi’s celebration of Bel Canto traditionsin that same progressive work.

Or check out how “Don Carlo” is an opera about abject failure.

We also look at the variations between the different versions of “Macbeth.”

Or maybe looking at the evolution of religion and its portrayal in Verdi is more your style?

Or how his style evolves from the seeds planted in “Ernani” and “Nabucco.”

We also look at the 5 best musical moments of “Un Ballo in Maschera” or how four duets make up the backbone of “La Forza del Destino.” There is also a look at the major motif of “Simon Boccanegra.”

Enjoy!

Categories

Special Features