Criticism on Fridays: The Apparent Well-Being of German Musicians

Humanistic Approach Hopelessly Loses to Laws, Management, & Market Law

By Polina Lyapustina(Photo: Jon Tyson)

Every Friday, Polina Lyapustina delivers a short essay on some of the most sensitive topics in the industry with the intent of establishing a dialogue about the opera world and its future.

This week, I tried to flee from the grave feelings I experienced last week working on my piece about the situation with the Met Orchestra Musicians, so before diving further into this issue next week, I turned my attention to the situation in Germany, where the government supports culture and musicians in ensembles keep their income, while the freelancers are supported by the government directly.

It is a dreamland, where the Bavarian State Opera works with scientists to test hypotheses about public safety, and a complete air change in the Nationaltheater is guaranteed every 9.5 minutes. A place where stunning performances are streamed every Monday for everyone in the world for free.

Sounds good. But we shouldn’t forget the protests in Germany in November. Hundreds of musicians stood for their rights in Munich and Berlin and more in smaller cities. They must have a reason.

And once I started to talk to the local artists, I found loads of issues there too.

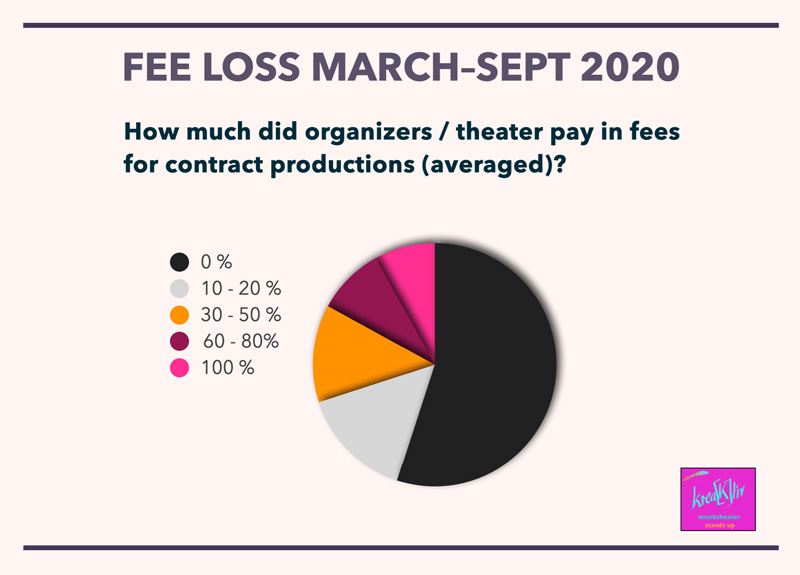

The main problem, wherein the major houses’ management plays an unfair game to the contract musicians, and cuts off their fees to just 10–20 percent of its true value. Just think about it. Up to 80 percent of the honestly earned money can be taken away just because the theatre knows that the artist will work anyway. The market rules so treacherously apply in difficult times against musicians. Companies know that musicians will perform anyway if given a chance. Smaller houses work better, paying up to 80% when their own situation is much more difficult — but they stayed totally inactive during the lockdown.

Numbers are cruel, and in this situation, which only concerns the freelancers — in some way a minority, the problem of humanity becomes even more visible. And if not for us, watching from the sidelines, then for the artists themselves.

I first realized it when I found out how the local community fights against these problems. KreaKtiv is an organization that helps artists to go through their financial, bureaucratic, and legal issues in Germany. And when I found their public page, I expected them to be critical, with numerous statements and anything else like that. But they were simply personal. For their materials, they chose videos and direct talks. They provide step-by-step guides about how to survive, answer simple or difficult questions with a smile, and they support people. I wondered why was the emotional climate was so important there?

The survey also showed that the psychological effects were also enormous — it turns out that many suffer from stress symptoms such as sleep disorders and panic attacks.

And then, in my talks to artists, the topic was mentioned in passing, but every time it appeared, it felt like a bad idea, and my interlocutors tried to get away from it, concentrating on the industry facts instead.

Suicide among musicians. Let’s talk about this topic.

And I, myself, started to write this essay with exactly the same approach — avoiding it, trying to pay attention to the facts I collected about the situation in Munich. And then, I heard Jonas Kaufmann and Joyce DiDonato speaking their hearts out at the press conference in Madrid just now, on Thursday.

With sirens from the street in Madrid, Kaufmann talked about how it feels to be privileged. Which now means to have the basic opportunity to work and also the moral responsibility to fight for others. And suddenly:

“I know of quite a high rate of suicides in our family of musicians. Also because they don’t see any future.”

The famed tenor stuttered talking about chances the industry can and must provide to “unknown artists” and his hope for this to end soon. When he finished, he covered his mouths with his hand, then crossed his arms over the chest. His struggle was visible, and like my interlocutors, he was uncomfortable with his words. Who would feel differently?

Joyce DiDonato then took over the topic:

“Opera is a competitive sport (…), there’s a star system, it’s an element of what we do, but this is not the industry, not the world of opera. We are a family. And we cannot do that without the make-up artists, and the stagehands, and the administrators, who are working themselves to the bone in this theater.”

But today, these words are as far from our reality as ever. We have become disconnected from each other and the problems of others. And this disconnection leads us to the bankruptcy of culture. The Mezzo-soprano returned us to humanity in her speech:

“Opera has an opportunity, in classical music, in culture, to represent the best of humanity. And when you script it away from a society we see time and time again, what are the results?”

At that moment, I put aside numerous facts about how the German opera industry survives the crisis and could I only think about how important a humanistic approach within the artists’ community truly is.

This art, this industry, this world is based on its people, and now we are losing them. Often their talents, but sometimes their lives. In this dystopic situation, what are we trying to save? Stages, companies? The government support and management’s decisions certainly make a difference, but with or without them it is hard either way.

#ArtIsWork was stated in 2020. But this year we must all turn to #ArtIsPeople.