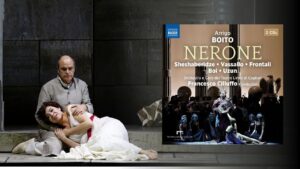

CD Review: Naxos’ ‘Nerone’

By Bob Dieschburg

An obsession more than just a pet project, the decade-long history of “Nerone” is but an imperfect indicator of the gargantuan scale Arrigo Boito envisioned for his imperial tragedy. The opera is an unwieldy amalgamation of music that–like the scapigliatura movement itself–occupies a liminal space: neither conformist nor truly progressive, but somehow perpetually discontent.

“Nerone” very much fits the profile of an in-between composition–both generationally and in terms of musical idiom, which harks more to Germany than to the melody-prone tradition of Italian opera. Still, it feels bumpy in parts, and this might explain the relatively sparse discography. Naxos now deems it time for a revival, offering an aptly crafted performance from the 2024 season at Cagliari’s Teatro Lirico.

Boito’s Swan Swang

The compositional fate of “Nerone” is not unlike that of “Turandot.” Like Puccini, Boito reportedly agonized over its final shape, and by the time of his death–in 1916–the opera was left unfinished. Its posthumous premiere was championed by none other than Arturo Toscanini, and an early rehearsal was attended by Puccini himself. Under such auspices, how could its premiere not have been triumphant?

The drama pivots between fire and spectacle–embodied by Nero himself–and the Christians, guided by Fanuel, a figure of moral gravity and strength. More so than “Aida,” Boito’s libretto evokes a tinged sense of grandeur as it intertwines private tragedy–the fate of Fanuel and the vestal Asteria–with historical cataclysms: from the persecution of Christians to the Great Fire of Rome.

A Heady Affair…

Yet for all its ambition, “Nerone” remains a very heady affair, burdened with too many soloists (seven principal roles) for any one voice to rise above musical anonymity. There are no true arias, and no clear high points, toward which the plot naturally builds. The opera is through-composed, but instead of focusing on one–or even a few–central characters, its near-cinematographic back-and-forth recalls the epics of 1950s’ Hollywood.

Certainly, Francesco Cilluffo was well aware of the headwinds he would face. Yet across all four acts he rose to the occasion: at the helm of the Cagliari orchestra, he deftly threads together passages of rhetorical declamation–”Gloria al tuo Dio,” for instance–with grand choral tableaux. He eases the transition between these mosaic-like sections, so that–in my impression–his relatively balanced take leans toward an Italianate sensibility rather than the orchestral emphasis Boito had drawn from the Germanic tradition.

Imperially Erratic

Cilluffo’s controlled, and flexibly paced interpretation also works to the advantage of the singers. As Nerone, tenor Mikheil Sheshaberidze convinces with a warm, if somewhat nondescript sound, faintly reminiscent of János Nagy on the nearly thirty-year-old Hungaroton release under Eve Queler.

Franco Vassallo offers a vivid Simon Mago, while Roberto Frontali brings full baritonal solemnity to the part of Fanuel. By comparison, my response to Valentina Boi as Asteria–a role at once mysterious and frenzied–remains lukewarm at best; notably because of the sharp edge in her acuti and, more crucially, a sense that her portrayal of the vestal is not entirely fleshed out.

I would not want to fault her, though, as so many of “Nerone’s” contradictions appear to coalesce in this single character. The opera itself hovers uneasily between fin-de-siècle allegory and historicized drama; it occupies an awkward position on the continuum of Italian melodrama that neither Cilluffo nor his cast could fully resolve.

For listeners drawn to Imperial Rome and to the religiosity and martyrdom of early Christianity, I would sooner recommend Feliks Nowowiejski’s “Quo vadis.” Although an oratorio, it offers what Boito’s “Nerone” tends to withhold: concision, linearity, and glorious melodic writing paired with bombast. Less erudite than “Nerone,” it is also far kinder on the ear.