CD Review: Megan Kahts’ ‘Dopo notte’

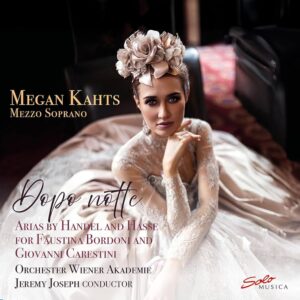

By Bob DieschburgMadame de Pompadour meets the brush of Joshua Reynolds: thus, or in a similar vein, one might describe the pastel-toned cover of Megan Kahts’ “Dopo notte.” In rococo drapery, the South African mezzo is bathed in a pervasive, yet sensuous, chiaroscuro.

Famously, one should not judge a book by its cover; yet here, what you see is exactly what you get: an intimate, playful homage to Faustina Bordoni and Giovanni Carestini, whose repertory Kahts inhabits in a twilight of storm and calm, pain and resolution.

Over the course of some fifty minutes, she positions herself as a highly competitive interpreter of opera seria–Handel and Hasse–standing in marked contrast to the inwardness of her previous album, “Dolce abbandono” (2002).

The repertoire balances the familiar with the rare. Handel staples such as “Scherza infida” (“Ariodante”) and “Mi lusinga il dolce affetto” (“Alcina”) anchor the program in tradition, while Hasse’s “Ti lascio in ceppi avvinto” (“Arminio”), “Vo disperato a morte” (“Tito Vespasiano”), and “Che sorte crudele” (“Cleofide”) remain largely absent from the playbills of today’s recital halls.

Variety also registers on a technical level. “Dopo notte, atra e funesta” lies in the middle and low registers, whose velvety depth is Kahts’ undisputed strength. By contrast, “Tempesta e calma” (originally written for Carestini) sustains a higher tessitura, which she projects with acute intensity.

Ornamentation is consistently virtuosic–though not indulgent–and her rhetorical insights make Kahts play with the tempi almost conversationally. They very much sit in the middle ground: neither too fast nor conspicuously slow, but consistent with Jeremy Joseph’s predecessors. At the helm of the Wiener Orchester Akademie, his “Dopo notte, atra e funesta” clocks in at six minutes and 51 seconds; Raymond Leppard, by comparison, is twenty seconds slower–due, notably, to Janet Baker’s luxuriant trills (Baker is on a complete recording of “Ariodante”).

Across its eight tracks, “Dopo notte” emphasizes the crispness of period sound–though Kahts’ expressive variations impart a surprisingly modern feel. I particularly appreciate her breath control and elegant, yet creative, legato in Hasse’s arias, which tend to be less contrapuntal than Handel’s.

In “Che sorte crudele,” she displays her signature warmth–in the melismas as much as in the melodic contour–even as the higher tessitura pushes her voice into noticeably brighter territory.

The Hasse selections, moreover, stake a claim for repertory reconsideration beyond the purely vocal. They allow Kahts to unfold her interpretive sensitivity–arguably more than the Handel pieces do.

As such, the release not only confirms Megan Kahts as a mezzo of considerable promise, but also positions her as an advocate for Baroque vocal literature that is not merely virtuosic but deeply felt. “Dopo notte” is a superb follow-up to “Dolce abbandono” and, through its chiaroscural qualities and pervasive melancholy, it commands attention.