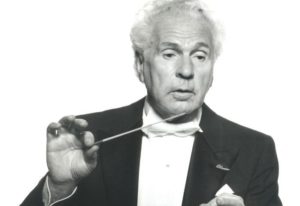

A Master at 100: A Celebration of the Legendary Career of Julius Rudel

By Gillian ReinhardJulius Rudel was one of the trailblazing leaders of opera and classical music in the twentieth century. Born on March 6, 1921 in Vienna, this year marks the 100th anniversary of the conductor’s birth. “I had the opportunity to know him up close and personal,” explained Tony Rudel, the maestro’s son. “His happiest moments were working with music and spending time with family.”

Rudel’s early life was marked by the looming threat of World War II. When his home country, Austria, was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938, Rudel left for the United States, where he studied conducting at the Mannes College of Music in New York City. Shortly after, Rudel began a long and successful collaboration with the New York City opera that spanned from 1944 to 1979. His influence in the City Opera extended to music as well as administration, and he served for many years as the New York City Opera’s general director.

Rudel is credited for his work in establishing the New York City Opera as a major force on the operatic world stage and his time with the company is fondly remembered as the “Golden Age.” He shepherded the Opera through its bankruptcy crisis in 1957 and established the company’s commitment to new works and American compositions. During his tenure as general director, Rudel oversaw world premieres from composers such as Carlisle Floyd, Thea Musgrave, and Gian Carlo Menotti. He conducted 19 world premieres at the City Opera himself. With an increasingly growing international career, however, he sought other ventures. “Leaving City Opera was not easy for him,” said Tony. “But, the time had come.”

In addition, Rudel worked closely with major as well as (at the time) unknown singers. He is credited for advancing the careers of bass Samuel Ramey and soprano Carol Vaness. Rudel also maintained a close partnership with soprano superstar Beverly Sills, who starred in several New York City Opera productions and became general director following Rudel’s departure in 1979. Rudel championed singers from marginalized backgrounds. During his tenure at the City Opera, Kathleen Battle, George Shirley, and Shirley Verrett—among many others—made their debuts.

Rudel had a special affinity for composers such as Kurt Weill, Massenet, Mozart, and Handel—a composer at the time not as commonly performed in the United States. He conducted the US premiere of Handel’s “Ariodante” and led a memorable production of “Julius Caesar” in 1966.

He is the only conductor to release full recordings of three different Massenet operas. Rudel’s interpretation of “Pelléas and Mélisande” became a definitive rendition of Debussy’s opera, and he was commonly known for bringing a “Viennese twist” to the great works of French opera.

He conducted the first ever recording of Massenet’s Cendrillon in 1979. Legendary mezzo-soprano Frederica “Flicka” von Stade sang the title role and reflected on her relationship with Rudel. She reminisced on recording the opera in London, remarking that Rudel’s leadership made the process fun and comfortable for her and the rest of the cast. “He was so completely at home with everything he did. Nothing was a struggle,” she explained. “It was like he was singing for you.”

Flicka compared Rudel to conductor and translator Thomas Martin and conductor and City Opera administrator Felix Popper. “They were trained in a beloved tradition of music,” she said. “They were just steeped in music. Their knowledge, their abilities, their talent—it was extraordinary. I feel so lucky to have trained with them.”

Rudel was also known for his passion for musical theater. Upon his return to Vienna in 1956, Rudel conducted a performance of “Kiss Me, Kate” at the famous Volksoper. It was the first time an American musical was performed in Vienna. “Many have described him as a ‘man of the theater,’” said Tony, citing Rudel’s recording of Verdi’s “Rigoletto” with Beverly Sills, Sherrill Milnes, and Alfredo Kraus. “That recording isn’t static. Every note is dramatic. The audience can’t help but feel engaged.”

Tony pointed to a lifelong love of theater as part of Rudel’s passion for the dramatic elements of opera. Rudel had a special affinity for American musicals, Tony explained, and recounted the conductor’s first trip to see “Sweeney Todd.” Rudel wrote his praise to Stephen Sondheim, who greatly appreciated the support from the noted conductor. Rudel maintained a long career with Broadway, bringing “Lost in the Stars” to the New York City Opera, and in turn conducting Weill’s “Threepenny Opera” in a 1989 Broadway starring Sting.

“Something spoke to him about drama,” Tony concluded. “He looked for emotive connectivity in every score.” Tony recalled a memory of his father studying the score of Poulenc’s “Dialogues of the Carmelites” in preparation for a run at the Met. He was able to replicate the intensity and emotion of the final scene simply on the piano. “Then, when I saw him with the orchestra at the Met, it was even more incredible.”

During and following his time at the City Opera, Rudel also served as artistic advisor of Wolf Trap and Philadelphia Opera, artistic director of the Philadelphia Lyric Opera Company and music director of the Caramoor Festival, Cincinnati May Festival, and Buffalo Philharmonic, in addition to hundreds of performances at the Met Opera. Rudel was the first artistic director of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. as well as the first host of a “Live from Lincoln Center” telecast.

Flicka fondly recalled filming a Christmas special with Rudel in Austria, when winter weather was imitated during an unseasonably warm autumn using artificial snow. “We just laughed,” she said. “We had such a nice time. Julius made everything around him easy. It could’ve been quite difficult to film, but instead, it was very fun.”

Flicka also pointed to Rudel’s relationships at home that serve as a testament to his life, in addition to his music. “He is so adored by his family,” she remarked. “Julius and his wife accomplished everything so beautifully—such a trusting, loving relationship.”

Rudel retired at age 90, following the release of 100 commercial recordings throughout his seventy-year career. In 2009, he received recognition from the US National Endowment for the Arts. Julius Rudel passed away in New York City on June 26, 2014.

“There were a lot of places he touched,” said Tony, including 1,300 performances at the Met Opera and City Opera and 7,000 performances around the country and the world. Of all of his nights at the Met, Rudel only missed one night’s performance. “Almost nothing could stop him,” said Tony.

Flicka, meanwhile, credited a “deep, deep respect for music” as the driver of Rudel’s career. Much like Martin and Popper, Flicka explained that Rudel, “was not only a musician and a conductor, but a man of letters and brilliantly educated. I feel so blessed, even more blessed as the years have gone by, that I worked with him. I treasure my memory of Julius Rudel.”

Categories

Special Features